Chicago Pensions Move to Center Stage

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Moody’s Investor Services cut Chicago’s bond rating from Baa2 to Ba1; Standard & Poor’s lowered the City’s rating from A+ to A-; and Fitch Ratings cut Chicago’s ratings from A- to BBB+. The action-forcing event appeared to be the assumption that the recent Illinois Supreme Court decision, which ruled unconstitutional the 2013 pension changes made for current workers in state plans, would make it difficult for Chicago to deal with its pension problems. The state’s constitution says that pension benefits for current workers “shall not be diminished or impaired.”

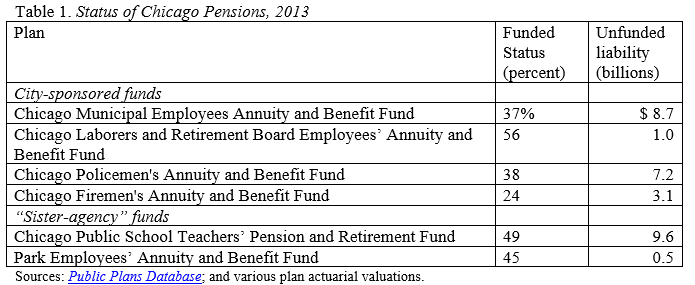

Chicago has six pension plans. Four are sponsored directly by the city and two are sponsored by “sister agencies” – the Chicago Board of Education and the Chicago Park District. (Moody’s also downgraded the Chicago Board of Education from Baa3 to Ba3 and the Chicago Park District from Baa1 to Ba1.) In 2013, these six plans were 40 percent funded and had a combined unfunded liability of $30 billion (see Table 1).

One explanation for the poor financial status of Chicago’s pensions is that the city’s plans are governed by Illinois state law, which sets the funding rules for the pension plans of its largest cities and counties. Up until 2015, the statute defined the employer rates for these plans as a multiple of the employee contribution. The resulting employer contributions have fallen far short of actuarially required amounts. Beginning in 2015, the statute set the employer rate actuarially, except for Park Employees, such that the plans will be 90 percent funded by 2055 (2040 for the Police and Fire Funds). Under the statute, Teachers’ plans for the largest cities and counties have always been “actuarially funded.”

In 2014, Chicago passed legislation that would raise employer and employee contributions and cut cost-of-living adjustments for current members of the Municipal and Laborer’s Funds, effective January 2015. Challenges to the cuts in these two systems, which had been on hold pending the Illinois Supreme Court decision on state pension cuts, will resume July 9. No changes have been proposed for existing members of the Police and Fire Funds, nor for the funds sponsored by the “sister agencies.”

In a 2013 study on the burden of pensions on 173 cities – sparked by the contention that pensions were responsible for Detroit’s bankruptcy – we concluded that generally pension costs were not a major burden for most cities. On average, annual required contributions to both the city’s plan and required contributions to state plans amounted to 7.9 percent of city revenues. Chicago, however, was a stark outlier, with required pension contributions amounting to 17.0 percent of revenues. (Chicago was #2; Little Rock, AK was #1 at 17.6 percent and Aurora City, IL was #3 at 16.1 percent.)

The options, at this point, seem limited. It is unlikely that Illinois voters will change the non-impairment clause in the constitution, and, given the Supreme Court decision, public employees have little incentive to compromise on benefit cuts. That means Chicago most likely will have to pay off $30 billion in unfunded liabilities. These funds can come from cutting all other government spending to the bone or by raising taxes.

Of the largest 25 cities, Chicago was #9 in combined property and sales tax revenues as a percentage of personal income in 2012. Paying off the $30 billion in unfunded liabilities would raise the tax burden by about 40 percent. Such an increase would make Chicago #3 behind Baltimore and New York, which are already funding their pensions.