Chicago Pensions – Redux

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Who’s responsible for the Chicago Teachers Pension Fund?

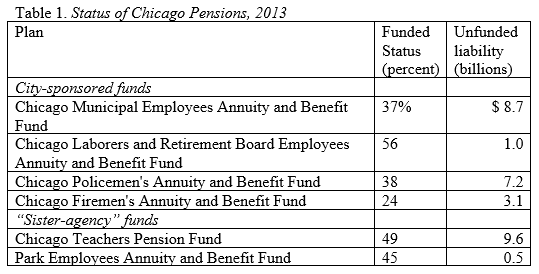

In response to the Illinois Supreme Court decision that the 2013 pension changes made for current workers in state plans were unconstitutional, all the major rating agencies cut Chicago’s bond ratings. Interestingly, most of the press accounts described Chicago as sponsoring four retirement plans – Municipal Employees Fund, Laborers Fund, Policemen’s Fund, and Fireman’s Fund. Few articles mentioned the two plans sponsored by “sister agencies” – the Chicago Board of Education and the Chicago Park District. The plan for Park Employees is tiny but the Teacher’s plan is large and has an unfunded liability of almost $10 billion (see Table 1).

My question: Who is responsible for the unfunded liability associated with the Teachers Fund? In 2014 when Mayor Rahm Emmanuel struck a pension deal with city workers, it applied only to Chicago’s Municipal and Laborers’ employees. Police, fire, teacher and park employees were excluded. Police and fire are always a complicated issue, but why leave out the teachers?

Here’s what I know about the Chicago Teachers Pension Fund (CTPF). The CTPF is funded through contributions from employees (7.5 percent of payrolls), the Illinois state government, and the Chicago Board of Education. (I wonder if the State contribution is an effort to compensate for the fact that Chicago residents, through the state income tax, contribute towards Illinois State Teachers Plan even though Chicago Teachers do not participate.)

Under a 1997 Illinois statute, the Chicago Board of Education is only required to contribute to the CTPF if the funded ratio drops below 90 percent. In that event, it must contribute amounts that, combined with other sources, will bring the CTPF to 90-percent funded by 2045. The funded ratio first dropped below 90 percent in 2004 and has continued to decline further since then. As a result, the Board should have made increasing contributions to the plan from 2006 to the present.

It appears that the Chicago Board of Education made the required payments in 2006-2010. In April 2010, however, the General Assembly passed SB1946 that dramatically lowered required pension contributions by requiring the Chicago Board of Education to cover only the “normal cost” in fiscal years 2011, 2012, and 2013.

Beginning in 2014, the Board was once again required to make full contributions to ensure the CTPF would be 90-percent funded by 2059 (once employees’ and the State’s contributions are accounted for). In 2014, the funded ratio for CTPF was 51 percent and, based on the actuarial valuation, the required pension contributions (from all non-employee sources) were about $560 million. The State contributed roughly $12 million to the pension, so the Chicago Board of Education was on the hook for $548 million. The Board came up with the money. I hope that the Board came up with the money in 2015 as well, but the annual financial reports are not available yet.

The only effort to fix the situation is recent legislation at the State level to redirect some property tax revenues from the Chicago School Board to the CTPF. The bill reduces the Chicago School Board levy from 3.07 percent to 2.81 percent of all taxable property within the Chicago Public Schools District and deposits the 0.26 percent directly into the CTPF. Based on the property tax revenues of the Chicago Public Schools in 2014, the redirected funds would amount to roughly $190 million dollars each year. On April 14, 2015, the bill passed in the Illinois House and is now waiting to be voted on in the Illinois Senate. Of course, if the bill passes, $190 million less will be available to fund Chicago schools.

So the story, as I see it, is as follows: 1) The CTPF plan is underfunded by $10 billion. 2) The statutorily required contribution from the Chicago Board of Education is only about 80 percent of the Annual Required Contribution under the Governmental Accounting Standards Board. 3) Nobody seems to be trying to fix the situation.

The Mayor has suggested that he would support legislation to consolidate the CTPF into the Illinois Teachers Plan. That seems an unlikely event (and may actually cost the residents of Chicago more as the Illinois Teachers plan is worse funded than the Chicago Fund). I think that the residents of Chicago should consider themselves on the hook for the $10 billion.