Child Care Credits for Social Security

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

The time has come to recognize that child care erodes women’s earnings.

The Social Security actuaries recently costed out a bill that would provide caregiver credits for individuals out of the workforce who care for children. This legislation, like other proposals, reflects an effort to improve the adequacy of old-age benefits for women. In recent decades, caregiver credits have become a near-universal component of public pension systems in higher-income OECD countries.

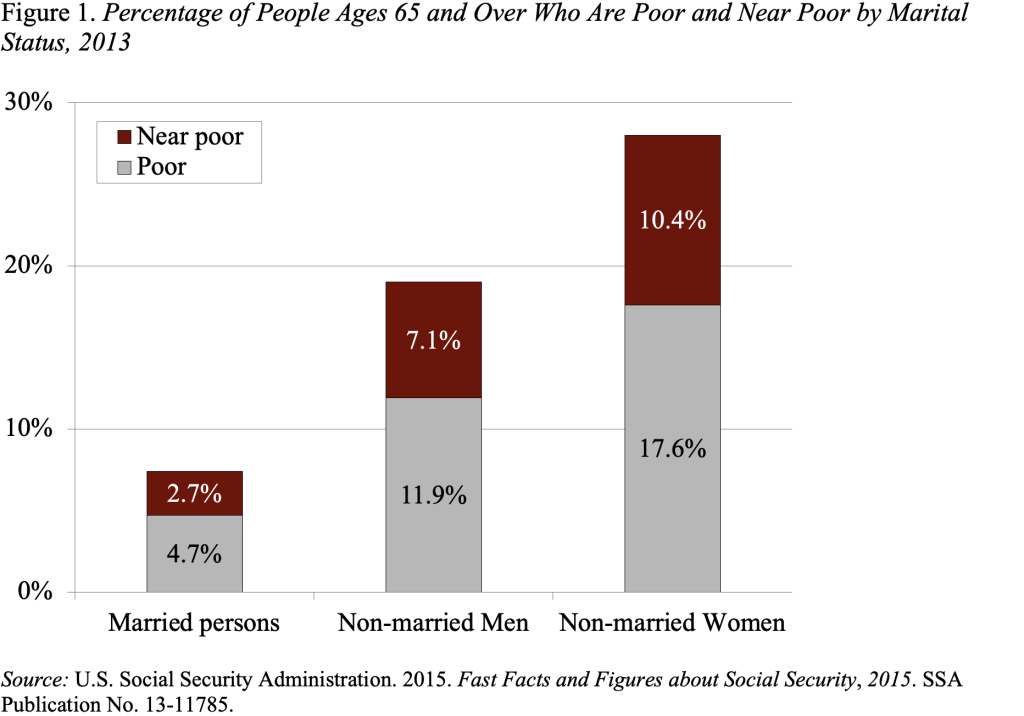

Older women remain a pocket of poverty in an otherwise improving landscape. In 2014, the poverty rate for those 65 and over was slightly lower than for those aged 18-64 (10.0 percent vs 13.5 percent). But older women without a husband experience much higher poverty rates. As shown in Figure 1, 18 percent of non-married women fell below the poverty line ($12,000 in 2014) and another 10 percent were classified as “near poor” with an income less than 125 percent of the poverty line.

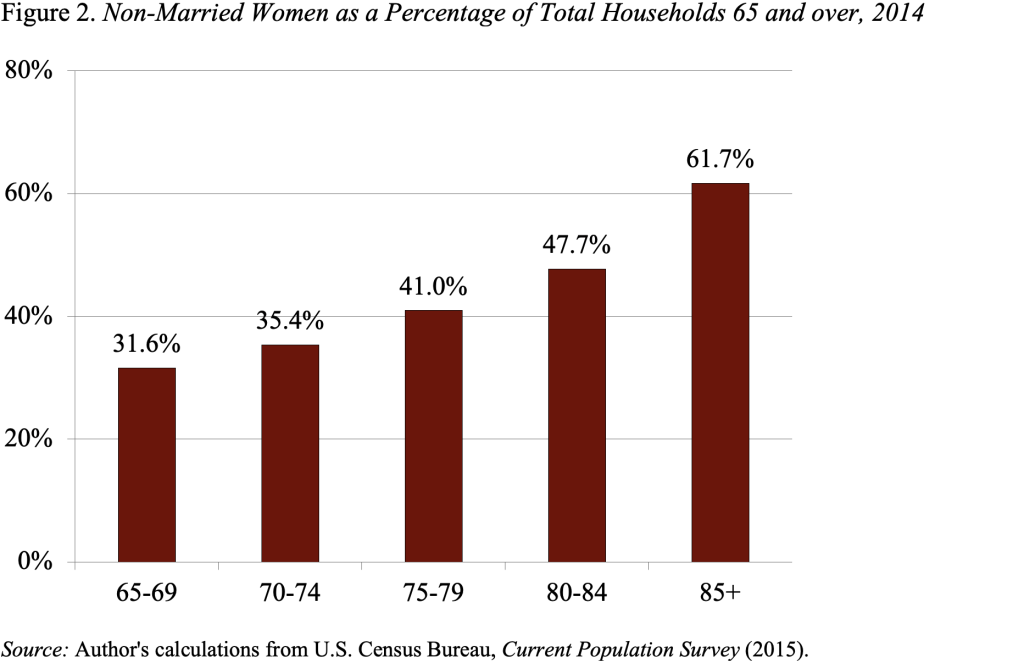

Not only do older single women have high levels of poverty, but they are a significant portion of the elderly population, particularly at older ages (see Figure 2).

Why do so many women end up poor? The answer is twofold. First, the retirement income system in the United States is based on earnings, and women have low earnings for three reasons. First, they have lower wages. Even women who are employed full-time earn about 20 percent less than men. Second, they are more likely to work part-time, which reduces their hourly wage as well as their hours worked. Finally, women spend fewer years in the labor force. As a result, women end up with less retirement income.

Second, while unmarried women are in trouble from the start, married women are okay for a while. However, they typically outlive their husbands and see a significant drop in their retirement income when the husband dies. The household’s Social Security benefit declines by one third (if the wife has no earnings history) to half (if her earnings equal her husband’s). In the case of employer-provided pensions, wives are much less likely to have their own, and even if their spouse had opted for a joint-and-survivor annuity, benefits will decline. In terms of 401(k) plans, we really don’t know what draw-down patterns will look like. But the risk is that accumulated assets are spent during the illness that led to the husband’s death.

The goal of the child care credit is to raise the woman’s own retirement benefits, which is increasingly important given the substantial share of women retiring today who have never married or are divorced. The specific proposal in H.R. 4529 submitted by Rep. Patrick Murphy (D-FL) would provide up to five child care drop-out years when calculating an individual’s Social Security benefits. That means women would be able to average their earnings over 30 rather than 35 years; fewer years of zero earnings will produce a higher average and a bigger retirement benefit.

Many other designs are possible to account for years of child care, but the time may have come to recognize the impact of child-bearing on women’s earnings histories.