Dallas Police and Fire Pension Plan Problems Caused by Extraordinary Decisions

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

This extreme situation tells us little about public plans in general.

The Dallas Police and Fire Pension Plan has received a lot of press attention recently. My view is that the situation is extraordinary and says little about what is going on with state and local pensions generally. It is a story of wild investments that produced large losses and a very large Deferred Retirement Option Plan (DROP). A DROP is an arrangement under which employees entitled to retire continue working and have their monthly benefit deposited in a notional DROP account where it earns interest and can be taken out as a lump sum.

As a result of poor investment policy and consistent underfunding, the Dallas Police and Fire fund went from having enough assets to cover 72 percent of its liabilities in January 2011 to having only 45 percent in January 2016. Subsequently, in 2016, when the DROP participants caught wind of talks to reduce their benefits, they took notice of the steep decline in asset values and started withdrawing their money, exacerbating the problem. The funded ratio at this point probably stands at around 35 percent.

The investment problems stem from 2006 when the Board decided to diversify its investment strategy to reduce the risks associated with equities. These diversified investments included luxury homes in Hawaii, student housing in Texas, and raw land in Idaho and Colorado.

A Dallas Morning News expose in 2013 describes one of the Hawaiian homes as consisting of six buildings, a championship golf course, two infinity pools, a sculpture garden and a large entertainment pavilion. In 2013, it had been on the market for five years with no one willing to pay the asking price of $22 million, so the fund – which managed these investments internally –started renting it out for as much as $15,000 per night to recoup some of its operating costs.

Returns initially looked good, in large part because the properties had not been regularly appraised and, in some cases, improvements and operating costs had been added to their original value. Once the assets were revalued, the losses were evident.

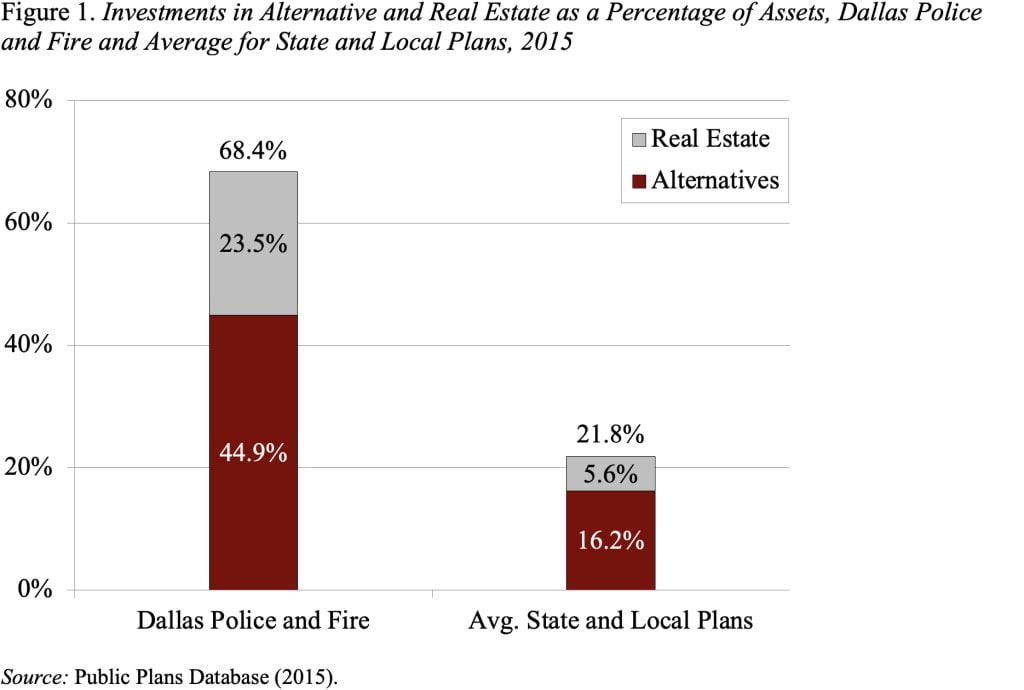

Some commentators imply that the Dallas Police and Fire Pension Plan is the tip of the iceberg in terms of public plan investment problems. The data suggest otherwise. Dallas has 68.4 percent of its assets in alternatives and real estate compared to an average of 21.8 percent for our sample of 160 state and local plans (see Figure 1). It has the highest ratio of alternatives and real estate of any plan in the nation; the next closest competitor is Texas County & District Plan at 53.5 percent.

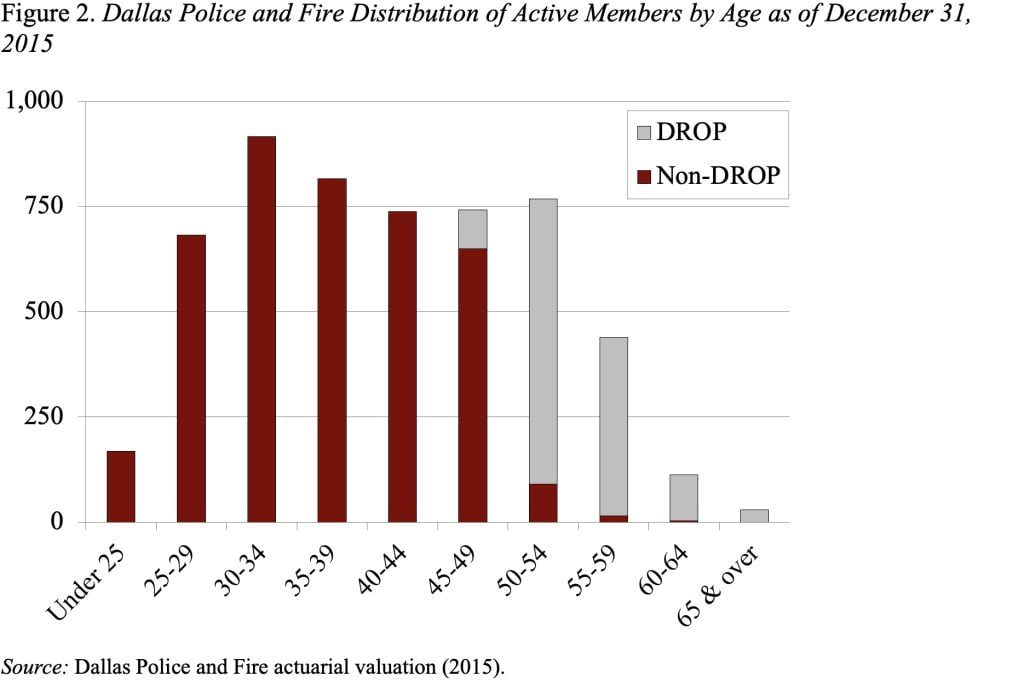

My sense is the Dallas Police and Fire DROP is also extraordinary. As noted, a DROP allows employees entitled to retire to continue working and have their monthly benefits deposited in a notional DROP account where they earn interest. The Dallas Police and Fire DROP stands out for a number of reasons. First, only 16 percent of state plans and 37 percent of local plans have DROPs. Second, almost 100 percent of Dallas Police and Fire employees participate in the DROP, and the DROP has no limit on how long they can participate. As a result, DROP participants account for a large portion of the workforce (see Figure 2). Third, until 2014, the DROP paid interest of 8.5-9.0 percent on its balances. As a result of the pattern of participation and interest rates, the Dallas Police and Fire DROP balances accounted for 56 percent of plan assets in January 2016. That is, more than half of plan assets are available for immediate withdrawal, which seriously exacerbates the plan’s financial problems. As a stop-gap measure, on December 8 the Board voted to halt further withdrawals from the DROP until next month’s Board meeting.

In short, the Dallas Police and Fire situation is an extreme case and tells us little about public plans in general.