Declining Wealth and Rising Cost of Necessities Are the Real Worries When It Comes to Senior Poverty

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

But the real cost of necessities and declining wealth of those approaching retirement should set off alarm bells.

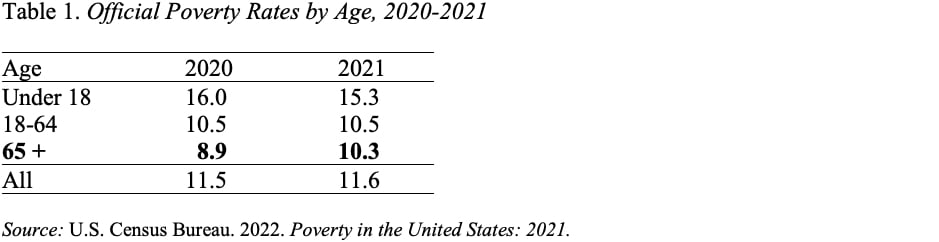

In the wake of the release of the Census Bureau’s Poverty in the United States: 2021, observers have noted that the poverty rate among the elderly ticked up from 2020, while it declined or remained unchanged, respectively, for those under age 18 and those ages 18-64 (see Table 1).

Personally, I would not put too much weight on a one-year change in the poverty rate. But talking about poverty among older people does raise two important causes for concern. First, while the official poverty rate was a major innovation when it was first introduced in the late 1960s, it is very crude and tells us little about the well-being of older Americans. Essentially, the thresholds were set at a minimum diet for families of different sizes multiplied by three. The 1960s’ numbers have been adjusted for changes in the Consumer Price Index to produce today’s poverty thresholds of $12,996 for a single individual 65+ and $16,379 for a couple 65+. These amounts are roughly half what experts at UMass Boston calculate older households need to cover basic and necessary living expenses. Hence, being above the poverty line does not mean all is well.

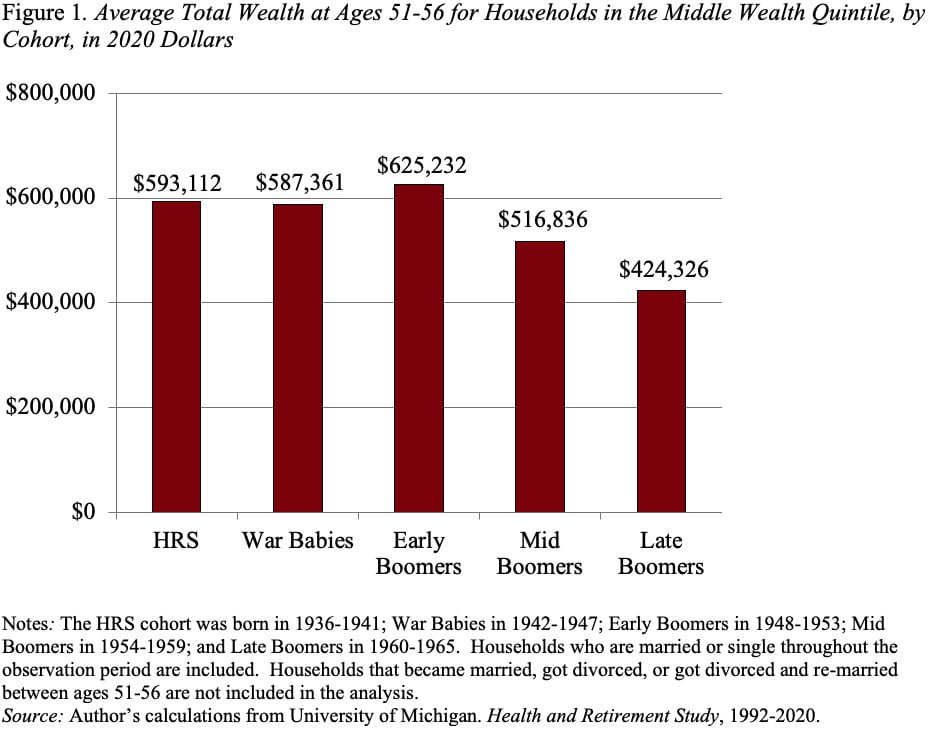

Second, data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) show that the wealth holdings of people entering retirement have actually declined across cohorts (see Figure 1). For this exercise, household wealth includes: 1) Social Security wealth as measured by the expected discounted value of future benefits; 2) wealth in employer-sponsored retirement plans, including both 401(k)-type and IRA balances and the present discounted value of expected benefits from a defined benefit plan; 3) financial assets less any outstanding debt; and 4) the value of the primary residence less any outstanding mortgage debt.

The decline in wealth is largely due to two factors: 1) lower Social Security wealth as the gradual increase in the Full Retirement Age from 65 to 67 reduced lifetime benefits; and 2) fewer assets in retirement plans, which most likely reflects adverse labor market experiences during the Great Recession.

In short, while the one-year increase in the poverty rate for those 65+ probably says little about the economic well-being of older Americans, the downward trend in wealth holdings does not augur well for the future.

I hope that politicians who talk about cutting Social Security are paying attention.