Department of Labor’s Rule for ESG Investment Hasn’t Changed from Trump to Biden

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

ESG factors can be considered only to garner the highest risk-adjusted returns.

In Wisconsin and Texas district courts, plaintiffs are suing government officials to block the Department of Labor’s new rule on ERISA investment duties with regard to environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors. They contend that the so-called “Biden Rule” violates the law and, in the case of the Texas complaint, has hurt businesses. In response to these suits, Mark Iwry, a former Treasury official and probably the nation’s leading expert on the policy and law of retirement plans, has submitted Amicus briefs – not to take sides – but to clarify that, despite a lot of ping-ponging rhetoric across administrations, the final “Biden Rule” and the final “Trump Rule” are virtually identical.

The reason for the similarity is that both rules are tightly constrained by ERISA, as interpreted by the Supreme Court in 2014 (Fifth Third Bancorp v. Dudenhoeffer). The Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision, said very clearly that fiduciary investment decisions must be made for the exclusive purpose of maximizing risk-adjusted returns. Both the final Biden Rule and the final Trump Rule make it very clear that a fiduciary cannot make an investment decision for any other purpose. The Biden Rule says ESG factors can be considered only to the extent that they are relevant to a risk-return analysis, not as collateral benefits. The Trump Rule effectively reaches the same conclusion, but states it in the negative – ESG factors must not be considered to the extent they are not a “pecuniary factor.”

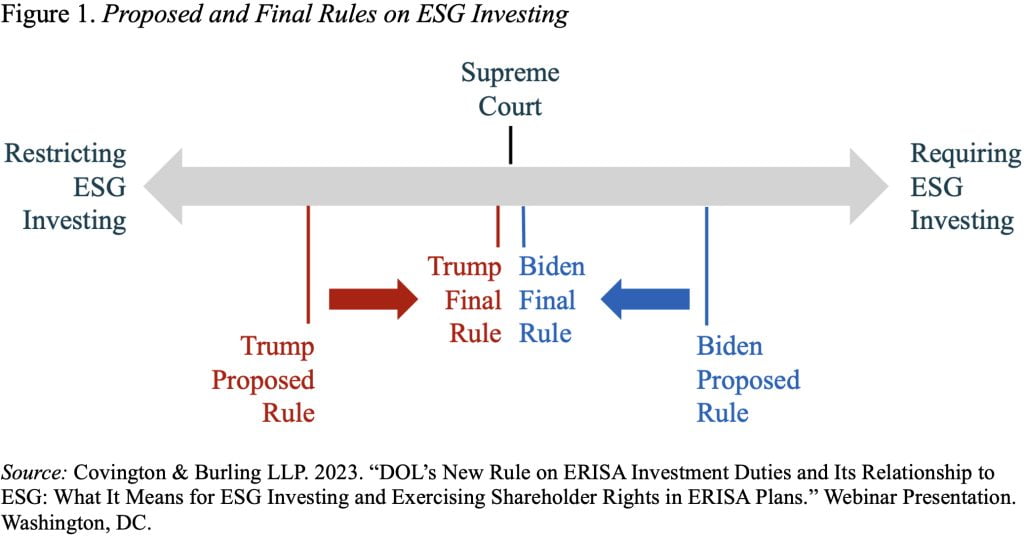

So why are the Trump and Biden Rules generally perceived as being inconsistent with one another? Probably because, in each administration, the proposed rules that preceded the final rules staked out diametrically opposed views on the appropriateness of using ESG factors in investment decisions (see Figure 1). The proposed Trump Rule created the impression that the final rule would prohibit any consideration of ESG factors, which it did not do. Similarly, the proposed Biden Rule created the impression that the final rule would require consideration of ESG factors, which it did not do.

Both rules do make a narrow exception to permit consideration of collateral benefits to break a tie, provided risk-adjusted returns are not sacrificed. The Biden Rule uses slightly different language to define a tie and removes the formal requirement that ties need to be documented, but the thrust of the narrow exception remains the same. Importantly, ties occur very rarely because it is so difficult to establish that two investments would “equally serve” the financial interests of the plan in the first place.

The bottom line is that the provisions regarding consideration of ESG factors in investments covered by ERISA are very clear. Such consideration is appropriate when – and only when – it is relevant to risk-return analysis, with the goal of that analysis being the maximization of financial benefits to plan participants. And – despite the political rhetoric on both sides – that constraint does not change from one administration to the next. The DOL and plan fiduciaries must follow the Supreme Court’s very clear interpretation of ERISA.