Does Public Pension Funding Affect Where People Move?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

A recent study suggests unfunded pension liabilities deter moving, albeit the effect is small.

The Center for Retirement Research at Boston College has explored the impact of pensions on state and local finances, including their influence on overall budgets, borrowing costs, and the fiscal health of troubled jurisdictions. Overall, this research found that pensions play only a modest role. However, one other way that pensions may impact public finances is through where individuals choose to live. And a recent study explores the role that unfunded pension liabilities play in migration from state to state

The ability to move has been a central tenet of the American dream. Important periods of U.S. history, such as the Gold Rush or the Dust Bowl, saw large groups of people moving in pursuit of greater opportunity. Historically, Americans move more frequently than residents of many other developed countries. For that reason, U.S. migration patterns tell an important story, one that sheds light on larger economic, financial, and cultural shifts happening within the country.

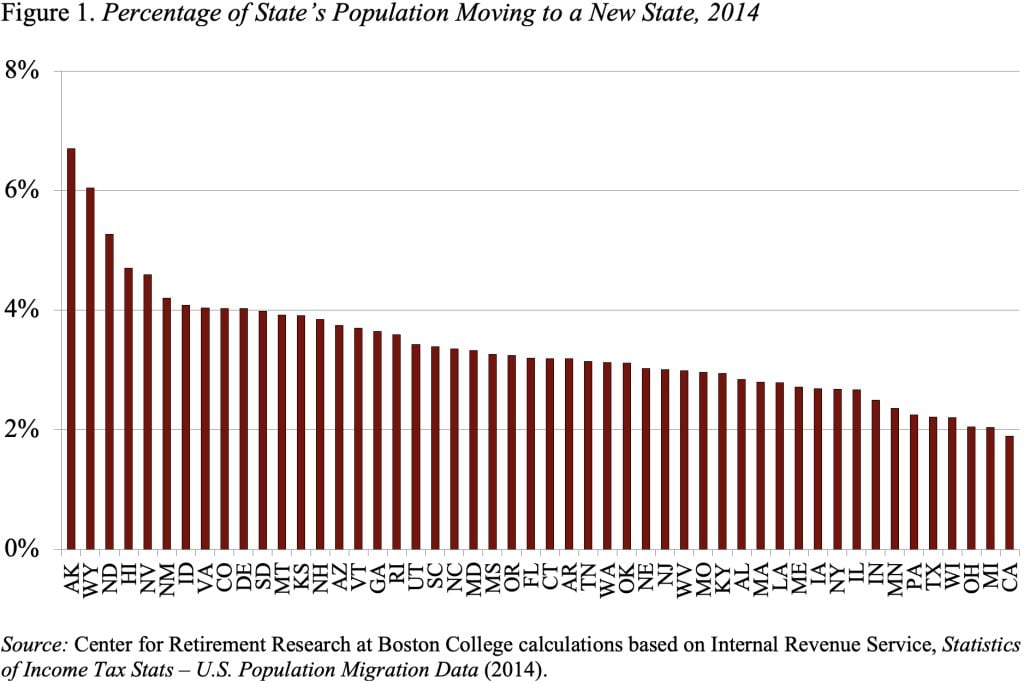

About 3 percent of the population – 9 million people – move to a different state each year, and the percentage varies substantially by state. For example, in 2014, the out-migration rate ranged from just under 7 percent of the population in Alaska to 2 percent in California (see Figure 1).

The question of interest is why someone in, say, New Jersey chooses to leave the state. And, do a state’s pension finances have anything to do with it? To answer this question, we use a regression to test how differences between an origin and destination state impact the proportion of households in the origin state that move to the destination state.

The data on mobility come from the Internal Revenue Service. If a taxpayer’s state geographic code changes from one year to the next, the taxpayer is considered a “migrant.” When compiled, the data show the number of households that leave each state, to every prospective destination state, for each year between 1992 and 2014. This rate is the dependent variable.

The independent variables include a control for distance and five other explanatory variables covering pension, financial, and economic factors. Given the origin-to-destination structure of the dependent variable, the independent variables are generally defined as the difference between the destination and origin state characteristics.

For example, the 2013 New Jersey and California average tax rates equal 5.6 percent and 7.2 percent, respectively. Thus, a person moving from New Jersey to California experiences a 1.6-percentage-point increase in average tax rate. Conversely, a person moving from New Jersey to Pennsylvania (which has a 3.0-percent average tax rate) experiences a 2.6-percentage-point decrease in the average tax rate.

The results of the regression show that economic factors such as more job openings and higher house prices attract migrants to a specific destination state. And financial factors (a higher average tax rate and debt), distance, and unfunded liability tend to decrease migration to that state.

While it is difficult to imagine that a state’s pension underfunding factors directly into a potential mover’s calculus, it is possible that negative media coverage of state finances could influence decisions on where to move. And the effect of unfunded pension liabilities is small; at most, it can be seen as one factor among many that collectively inform and motivate decisions to move.

The interesting news here, however, is that pension underfunding seems to matter.