Eliminating Social Security Provisions that Reduce Benefits for Some State and Local Workers Is Not the Way to Help Retirees

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

The real answer is that all state and local workers should be covered by Social Security.

President-elect Biden proposes to eliminate the Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP) and the Government Pension Offet (GPO). These provisions reduce Social Security benefits for workers with significant government pensions from jobs not covered by Social Security and for their spouses and survivors. Eliminating these provisions would be a mistake. They are well-intentioned attempts to solve an equity issue that arises because about 25-30 percent of state and local workers are not covered by Social Security.

Exclusion from Social Security creates two types of problems. First, employees lacking coverage are exposed to a variety of gaps in basic protection – most notably in the areas of survivor and disability insurance. Second, uncovered state and local workers can gain minimum coverage under Social Security and – until the introduction of the WEP in 1983 – could profit from the progressive benefit structure, which was designed to help low-wage workers.

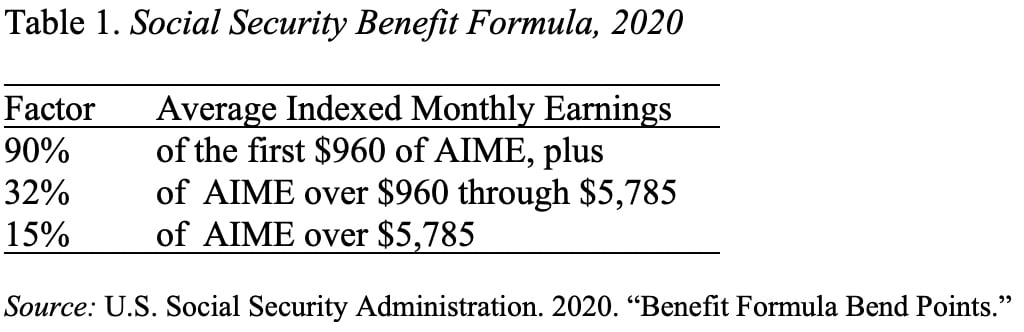

To see how that happens, look at the Social Security benefit formula. It applies three factors to the individual’s average indexed monthly earnings (AIME). Thus, in 2020, a person’s benefit would be the sum of 90 percent of the first $960 of AIME, 32 percent of AIME between $960 and $5,785, and 15 percent of AIME over $5,785 (see Table 1).

Since a worker’s monthly earnings are averaged over a typical working lifetime (35 years), a high-wage earner with a short period of time in covered employment looks exactly like a low-wage earner. Both would have 90 percent of their earnings replaced by Social Security.

Similarly, a spouse who had a full career in uncovered employment – and worked in covered employment for only a short time or not at all – would be eligible for the spousal and survivor benefits.

The WEP reduces the first factor in the benefit formula from 90 percent to 40 percent; the 32 percent and 15 percent factors remain unchanged. It is not a perfect solution – the benefit cut is proportionately larger for workers with low AIMEs, regardless of whether they were a high- or low-earner in their uncovered employment. Albeit, the WEP does guarantee that the reduction in benefits cannot exceed half of the worker’s public pension, which protects those with low pensions from uncovered work.

Several years ago, Rep. Kevin Brady (R-TX) introduced a bill with a new WEP formula. It involved two steps. First, the regular Social Security factors would be applied to all earnings – both covered and uncovered – to calculate a benefit. The resulting benefit then would be multiplied by the share of the AIME that came from covered earnings. Such a change would produce smaller reductions for the lower paid and larger reductions for the higher paid. That is a better approach.

Thus, the WEP would benefit from a little reform. But neither the WEP nor GPO should be eliminated. These provisions address a real inequity associated with having some state and local workers not covered by Social Security.

The bigger question, however, is whether it is worth the trouble of creating a whole new procedure when the real answer is to extend Social Security coverage to all state and local workers. Universal coverage would both offer better protection for workers and eliminate the equity problem.