Want People to Keep Working Longer? Expand the Earned Income Tax Credit

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

This could help extend the work lives of older Americans.

Older people need to work longer in order to ensure a secure retirement. Social Security will not replace as much pre-retirement income in the future as it does today, and employer-sponsored pensions also involve considerably more uncertainty given the shift from defined benefit to 401(k) plans. The challenge is to ensure that older Americans will offer their services and that employers will retain or hire them. One notion that we have been thinking about to encourage older people to stay in the workforce is expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit.

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) was introduced in 1975 as a modest temporary refundable credit for low-paid workers to reduce the effects of a rising payroll tax. Congress made the credit permanent in 1978, expanded it significantly in 1986 and in 1990, and in 1993 doubled its size to ensure that full-time minimum wage workers would not live in poverty. The EITC was designed primarily for workers with dependent children, who might otherwise turn to public programs for assistance. A small credit for workers ages 25-64 without dependent children was added in 1993.

While the EITC has significantly increased labor force participation among mothers with children, it does little for older workers for two reasons: 1) many older people do not have dependent children so their maximum benefit would be about $500 – too small to be salient and affect behavior; and 2) the EITC excludes workers ages 65-70. Significantly increasing the amount of the credit and extending the eligibility age to include those 65-70 would help older workers remain in the labor force to ensure a secure retirement.

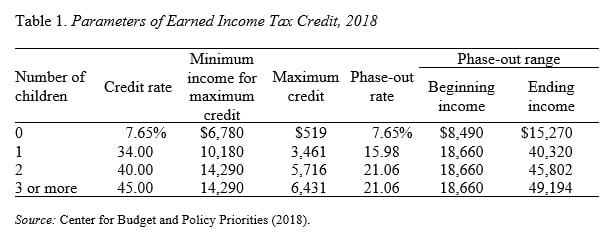

Table 1 shows how the EITC works. The amount of the credit first increases with earnings, reaches a plateau, and then falls as earnings increase further. For example, in 2018 the credit for a single taxpayer with two children is equal to 40 percent on the first $14,200 of income, reaching a maximum of $5,716. The credit remains at this level for earnings between $14,290 and $18,660, at which point it is phased out at a rate of 21.06 percent and reaches zero at $45,802. (The end of the phase-out is $5,690 higher for married couples.) In contrast, the maximum credit for a person with zero dependent children is $519, and the credit falls to zero once earnings reach $15,270.

To have an effect, however, the EITC benefit must be salient. A maximum benefit of $519 is not enough to grab anyone’s attention. It is unclear whether doubling the benefit would suffice or whether a maximum benefit in the $2,000 range would be necessary. Moreover, workers ages 65-70 need to work longer for a secure retirement, so the eligibility age should be raised. We estimate that an EITC expansion of this nature would cost about $300 billion over ten years. It would be a wonderful provision to include in the next tax bill.