It’s Harder than You Think to Spend Down Your 401(k) Account in Retirement

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Hoarding retirement savings is a risk.

At a recent conference, retirement experts concluded that the lack of an easy drawdown mechanism in 401(k) plans was the major challenge facing the 401(k) system. In 2014, the Treasury Department and the IRS issued guidance that made longevity annuities accessible to 401(k) plans and that enabled target date funds to include annuity contracts either as a default or as a regular investment option. But individual plan sponsors feel under siege by lawsuits and see little payoff to being innovative. At the same time, Congress is unlikely to mandate that annuities be a part of 401(k) arrangements.

So we are at a standstill. Millions of Americans – having been told that their retirement plans are automatic – will be handed a pile of money and told they are on their own. Neither academics nor policymakers really have any idea how they will behave. Recent studies show that people draw down their balances in retirement much more slowly than expected. But most of today’s retirees with a retirement plan have an old-fashioned defined benefit plan, so these studies have little to say about the likely behavior of those retiring entirely dependent on 401(k)s.

That said, I am more concerned about people hoarding their retirement savings than blowing them on a trip around the world. First, people seem to have a psychological attachment to their pile; they have spent a lifetime building it up and may be reluctant to draw it down. Second, people are fearful about end-of-life health care needs and want to be sure they have enough money to cover their expenses. Finally, people seem to have a desire to leave a bequest – perhaps ensuring their immortality! So, without some guidance, chances are high that retirees will deprive themselves of necessities.

One way to help may be to put more emphasis on the Required Minimum Distributions (RMD), which the IRS requires when individuals reach age 70½ and each year thereafter. The IRS does not claim that the RMD, which is intended to collect deferred taxes, is the basis of an optimal draw-down strategy. Yet an RMD approach satisfies four important tests of a good strategy.

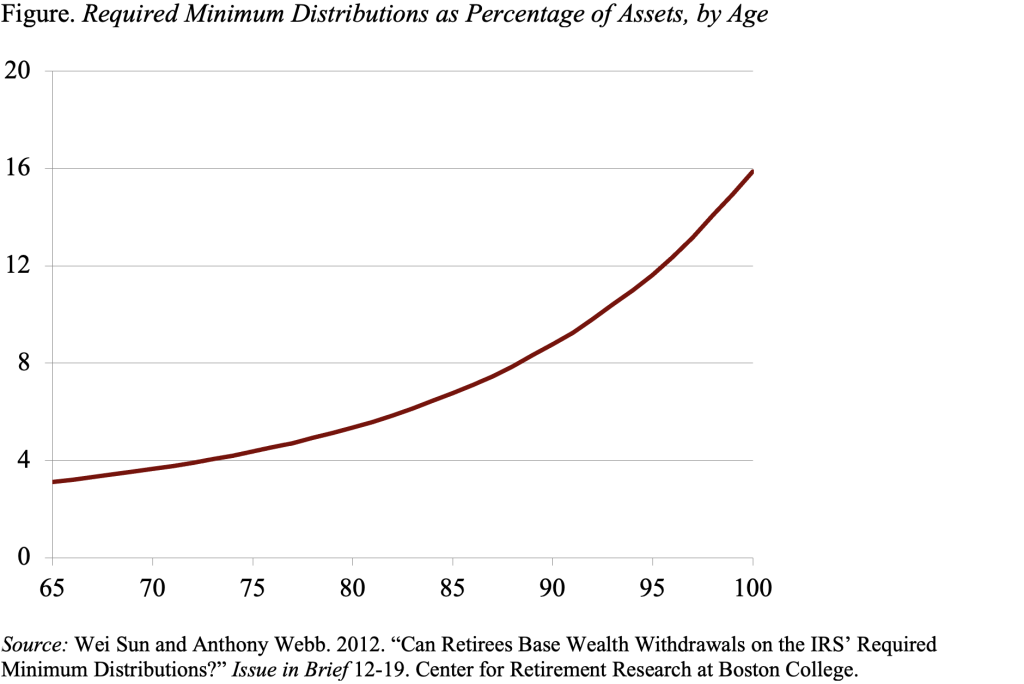

First, it is easy to follow. The IRS requires withdrawal percentages based on tables of life expectancies. Such a withdrawal schedule can be calculated for younger ages based on the same life tables used for the RMD rules (see Figure). Second, the RMD strategy allows the percentage of remaining wealth consumed each year to increase with age, as the retiree’s remaining life expectancy decreases. Third, consumption responds to variations in the value of the financial assets, because the dollar amount of the drawdown depends on the portfolio’s current market value. Finally, it reduces the incentive to chase dividends.

In a 2012 study, researchers compared the RMD approach with 1) other rules of thumb (such as living off the interest, basing withdrawals on remaining life expectancy, or taking out 4 percent each year) and 2) an optimal draw-down strategy that maximizes a household’s utility from consumption. The results of the horse race showed that the RMD strategy did ok. And it has the good features mentioned above.

It may be worth thinking about whether to publicize the message that people should feel free to spend the money that the government requires retirees to take out of their account.