Half of Today’s Households Are at Risk for Retirement

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Retirement security in 2019 and 2020: We need to fix our retirement system.

The release of the Federal Reserve’s 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) provides, once again, an opportunity to take stock of retirement security.

For this task, we use our National Retirement Risk Index (NRRI), which compares SCF households’ projected replacement rates – retirement income as a percentage of preretirement income – with target rates that would allow them to maintain their living standard and then calculates the percentage falling short.

A recent brief both updates the NRRI to 2019 and also estimates what the NRRI might have looked like if the SCF had been conducted in 2020.

Updating the NRRI to 2019 involves several steps.

First, households from the 2019 SCF replace households from the 2016 SCF. Next, 2019 data are incorporated in the equation used to predict financial and housing wealth at age 65. Finally, annuity income is re-estimated based on any changes in reverse mortgage and interest rates.

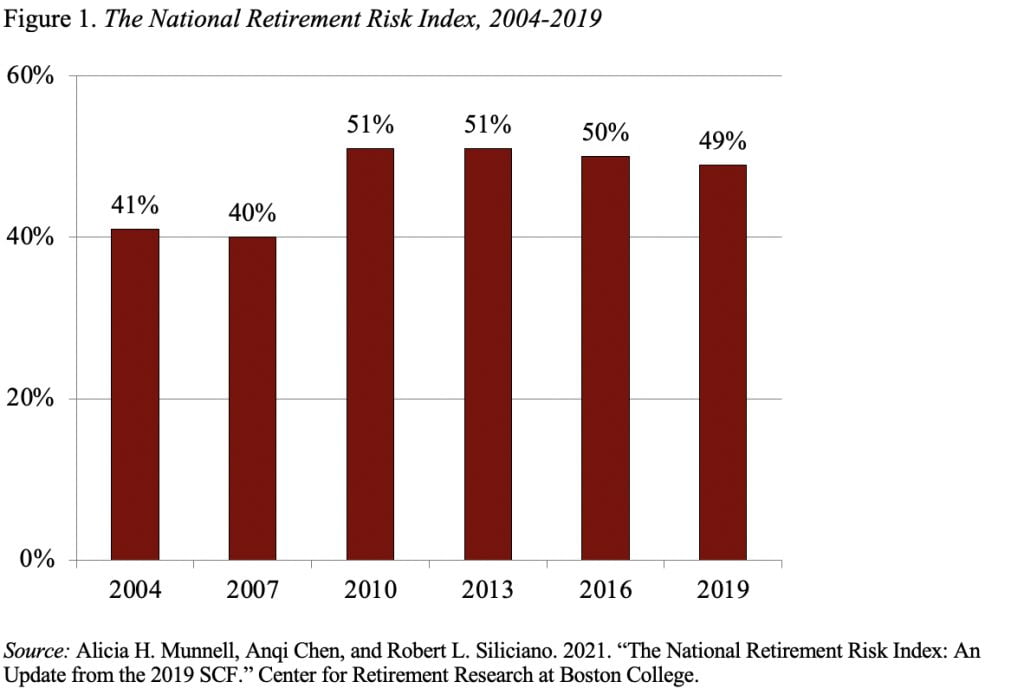

Because the three years from 2016 to 2019 were a period of solid economic growth accompanied by strong stock and housing markets, we expected the NRRI to have improved in this span. And it did. But the improvement was modest for several reasons.

First, the stock market gains were enjoyed primarily by those already not at risk.

Second, real interest rates continued to decline, which means that people will get less income from their accumulated wealth.

And third, the strong wage growth for lower-income groups, which is good news generally, led to lower projected Social Security replacement rates. As a result, the NRRI declined only from 50 percent in 2016 to 49 percent in 2019 (see Figure 1 below).

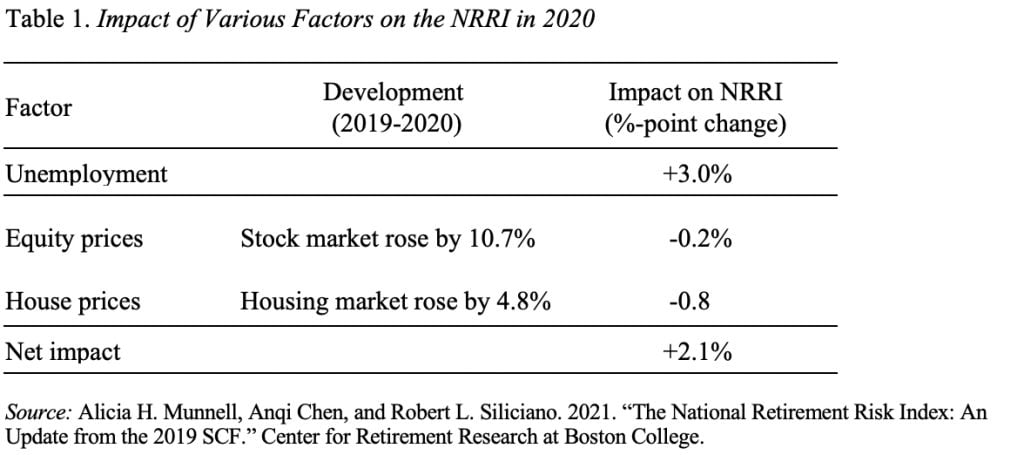

While the update for 2019 is useful and provides a benchmark for future surveys, it does not tell us about retirement security in 2020. COVID-19 and the resulting surge in unemployment have inevitably made the situation worse. Indeed, our estimate shows that if the SCF had been conducted in 2020 instead of 2019, the NRRI would have been 2 percentage points higher—51 percent versus 49 percent.

A 2-percentage-point increase in the NRRI might seem modest for the most calamitous economic event since the Great Depression. Indeed, two factors are at play here. First, the rise in house and stock prices, an unusual occurrence during a recession, partially blunted the impact of unemployment (see Table 1 below).

Second, the NRRI only measures whether a household is at risk, not the increase in the “savings gap” – the gap between actual and adequate savings. That is, many households who were already at risk have become increasingly worse off.

The bottom line is that updates to the NRRI confirm what we already know — half of today’s households will not have enough retirement income to maintain their preretirement standard of living, even if they work to age 65 and annuitize all their financial assets, including the receipts from a reverse mortgage on their homes. We need to fix our retirement system. Only universal coverage at work will allow workers to accumulate adequate resources to maintain their standard of living.