Has “Funding Relief” for Private Sector Defined Benefit Plans Gone Too Far?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Making liabilities look small doesn’t make them go away.

In doing background reading to figure out how many companies may follow IBM and reopen a closed defined benefit plan, commentators kept referring to “funding relief,” which – combined with the improved funded status and de-risking – has dramatically reduced the likelihood that a company would be forced to contribute to its plan. I had not been following the regulations for private sector defined benefit rules and was shocked at the extent to which legislation had severed the connection between interest rate fluctuations and required contributions.

Funding relief has involved backing away from the strict requirements introduced in the 2006 Pension Protection Act. That legislation – responding to the collapse of the dot-com bubble and the plunge in interest rates at the turn of the century – did two things. First, it reduced the period for paying off unfunded liabilities to 7 years. Second, it specified the interest rates to be used for discounting promised benefits – the corporate bond yield averaged over the preceding 24 months. (It actually set three discount rates that depend on the dates the benefits are expected to be paid – in less than 5 years, 5 to 20 years, and beyond 20 years. But the story is complicated enough without considering three separate rates.)

At the same time that Congress tightened funding standards, the Financial Accounting Standards Board changed the reporting requirements, forcing corporations to treat net pension liabilities as debt on the balance sheet.

Shortly thereafter came the Global Financial Crisis when the stock market and the economy collapsed. With the new funding and reporting requirements, the drop in funded status imposed real costs on sponsoring corporations – their balance sheets took a hit and they faced a sharp increase in required pension contributions.

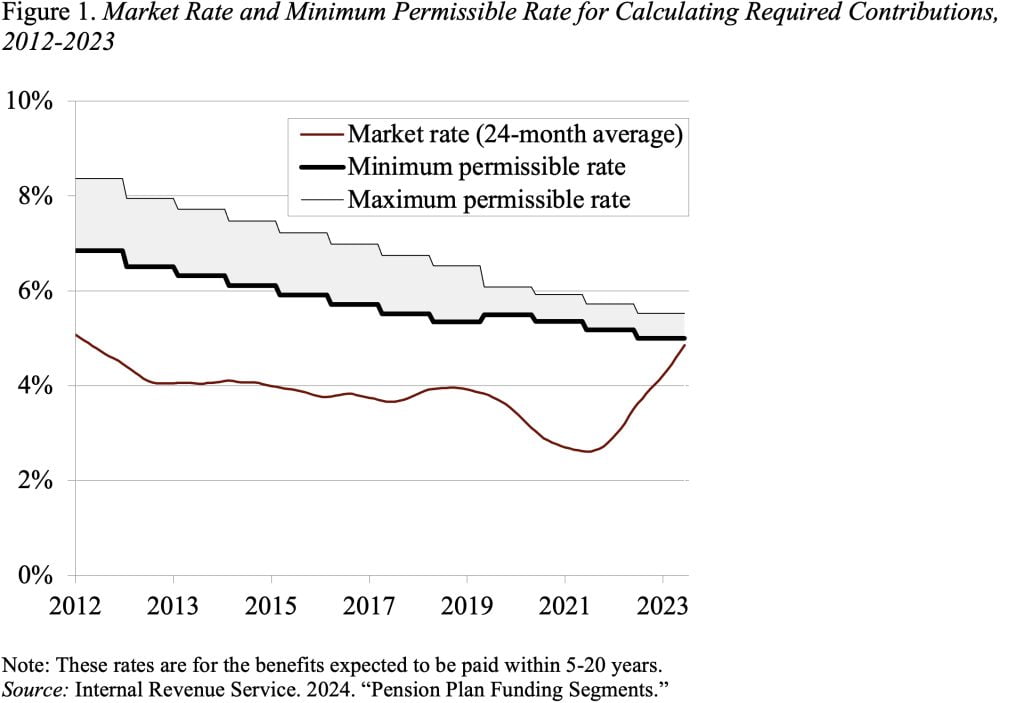

In response, Congress started its funding relief campaign. The first crucial piece of legislation was the 2012 Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act, which required that the interest rate established by the 2006 Pension Protection Act be averaged over the prior 25 years – a period when rates had been significantly higher. It also set the minimum and maximum rates at 90 percent and 110 percent of the average, respectively.

The 2012 legislation envisioned the corridor widening over time, which with market rates significantly below the corridor, would have decreased the funding discount rate – leading to increased liabilities and minimum required contributions. But additional iterations of funding relief prevented this widening from occurring. As a result, the rate used to calculate liabilities for funding purposes has been about 200 basis points higher than the “market rate” specified in the Pension Protection Act (see Figure 1).

The second and most dramatic pieces of funding relief were included in the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA). First, it set a floor of 5 percent on the 25-year average and narrowed the corridor around the average from 10 percent to 5 percent. The change comes just as the 25-year average was moving away from historically high rates, which would have eliminated the gap between the minimum permissible rate and the “market rate.” The legislation also permanently increased the amortization period from 7 years to 15 years, which increases the time for underfunded plans to reach full funding.

Sponsors must have lobbied for the ARPA provisions, and indeed higher assumed rates and the longer amortization period will allow many to continue their contribution holiday. But the plans’ liabilities have to be paid at some point, and plans contributing the minimum will have inadequate resources.

I’m not an expert on pension regulation, and it makes sense to protect sponsors against excessive volatility in the interest rates. But at this point, my concern is that funding relief has gone too far, and we may once again see problems down the road.