Here’s an Easier Way to Think about ESG Investing

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

At worst, it sacrifices return for social goals; at best it’s expensive active management.

The financial services industry seems exercised about the Department of Labor’s proposed rule limiting ESG investing for private pension plans covered by the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA).

The DOL states: “It is unlawful for a fiduciary to sacrifice return or accept additional risk to promote a public policy, political, or any other nonpecuniary goal.” Apparently, the agency undertook this initiative out of concern that ESG investments were becoming more and more popular with pension funds. It also wanted to eliminate confusion over DOL’s opinion on this type of investing, which has meandered over the years.

It’s an easy case to make that pension funds are not the place to accept lower returns to solve the ills of the world. ERISA makes that clear on the private side, and public plans have generally shunned sacrificing returns. Even if not illegal, sacrificing returns raises an agency problem: the people advocating for social issues – today’s politicians – are not the ones who will bear the burden of lower returns – namely, tomorrow’s retirees and taxpayers. Moreover, while such efforts often have powerful emotional appeal, they have no impact on the targeted companies, especially since the most recent incarnation of the “Vice Fund” stands ready to buy stocks diverted from standard portfolios.

But some advocates of ESG investing argue that they are not sacrificing return. Rather they contend that non-financial factors – such as a firm’s environmental impact, its relationship with communities where it operates, and its management culture – are relevant to long-term value. By integrating these ESG factors into existing methods of financial analysis, they believe that investors can reduce risk and earn higher returns, while supporting socially beneficial practices and outcomes.

But, I would argue that ESG is nothing special. When relevant, one would hope that any active manager would take into account a company’s personnel policies, its supply chains, and whether it’s leaking toxic chemicals. The problem is that once an asset manager begins the business of picking stocks, the price goes up. And study after study over decades has shown that, on average, active managers do not produce the returns to cover these fees. That is not to say some firms have not been successful, but on average they are not.

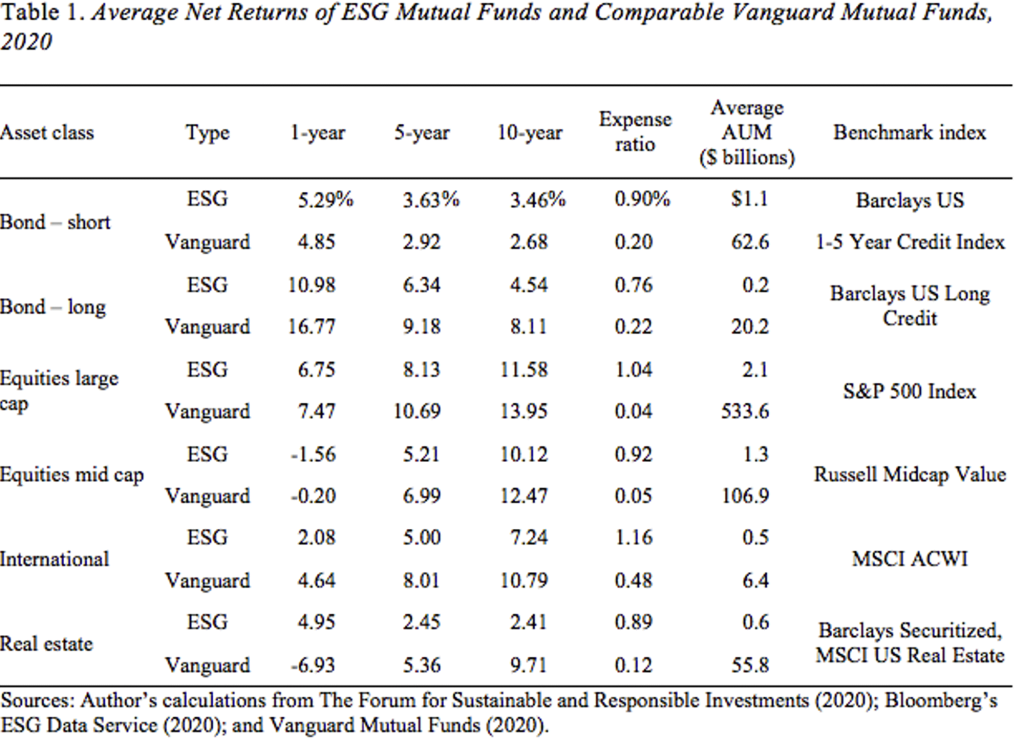

In a recent study, we looked once again at the impact of ESG investing on public plans and concluded that it led to lower returns. As a check on our results, we compared the returns on ESG mutual funds to unrestricted Vanguard funds over 1-year, 5-year, and 10-year periods. With the exception of the short-duration bond funds, the Vanguard funds out-performed their ESG counterparts, often by a considerable margin (see Table 1). The reason isn’t rocket science: the fees for ESG funds are roughly 80 basis points higher than their Vanguard counterparts.

Hence, regardless of how one views ESG investments – lower returns for social goals or simply high-priced active management – they probably do not belong on 401(k) platforms – much less as part of a default portfolio.