How Can We Better Support Family Caregivers? Pay Them

While the cost of elder care in the United States, whether paid for by Medicare, Medicaid or out-of-pocket, is substantial, most care is provided by family members for no compensation. Yet the burden on those family members can also be huge in terms of forgoing paid employment or work opportunities, time with family and friends, and general exhaustion.

An issue brief recently published by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College examines these costs, policies that can support family caregivers, and their preferences as expressed in focus groups. Here are some of its findings:

In 2021, there were about 38 million family caregivers in the United States who are estimated to have provided 36 billion hours of assistance to their family members.

Racial Disparities

White caregivers are more likely to be spouses and are older than Black or Hispanic caregivers, who are more likely to be the children or grandchildren of the people for whom they are caring. While 56 percent of White caregivers are ages 62+, only 37 percent of Black and 30 percent of Hispanic caregivers are this age. Just a fifth of White caregivers are under age 50 as compared to a third of Black caregivers and just over 40 percent of Hispanic caregivers. Non-White caregivers are also more likely to provide more hours of care per week.

Not surprisingly, the younger age and greater hours of caregiving for non-White caregivers have a greater impact on their ability to maintain their employment, which has ripple effects on their current and future finances as they earn less and contribute less to Social Security when working.

Limited Assistance

In terms of existing financial support, family caregivers can claim a Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit for out-of-pocket expenses of up to $3,000 for one dependent and $6,000 for two or more dependents. This tax break has limited utility for several reasons: the family member must qualify as a dependent; the credit is only for out-of-pocket expenses rather than compensation for the time and effort of care; and it’s non-refundable, meaning it’s not available to lower-income caregivers who have no federal income tax obligation.

The Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) provides up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave to workers who need to take time off to provide care. The lack of payment undermines the utility of this benefit for most workers. Fourteen states offer some form of paid family leave with the terms varying from state to state.

What Caregivers Want

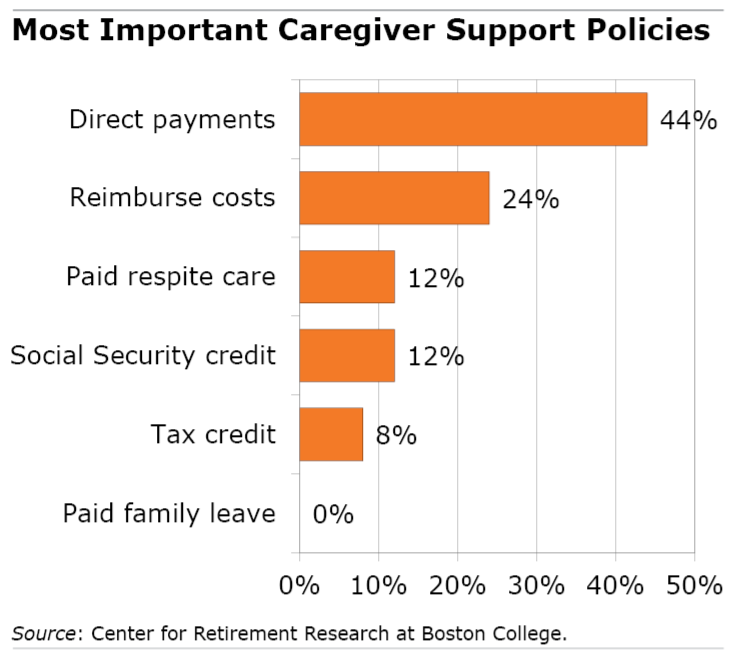

Researchers at the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College and the University of Massachusetts Boston conducted focus groups of family caregivers to learn what public policies would most help them. According to their report, the participants expressed great interest in being paid for caregiving and less for paid leave from work or tax credits. Many of them were not working, so would not benefit from paid leave, and proposals for only 12 weeks of paid leave were seen as too short to be of much utility.

Few of the caregivers were interested in suggestions to give them credits toward their future Social Security because this policy idea focuses on the future rather than their immediate financial needs. Some were interested in proposals for paid respite care to provide a much-needed break but they expressed concern about the quality of care that would be provided by those stepping in.

After direct payments, the greatest favorable response was for reimbursement for costs that the caregivers incur related to the support they provide their family members.

While these preferences were consistent among all participants, non-Whites favored direct payments and cost reimbursement to an even greater degree than White caregivers. This discrepancy no doubt reflects the greater impact on their employment due to their average younger age as cited above.

The ability of family members to provide necessary care to both older and younger disabled adults relieves pressure on the overburdened and fractured care network of nursing homes, assisted living facilities and home care providers, as well as public budgets, especially Medicaid. The pressure on this system will grow as the need for elder care doubles between 2030 and 2050 when the baby boomers reach their later years.

It would make sense to do what we can to better support family caregivers. This study makes it clear that the best way to do so is to provide financial assistance to family members, both in terms of compensation for their caregiving work and reimbursement for out-of-pocket costs.

For more from Harry Margolis, check out his Risking Old Age in America blog and podcast. He also answers consumer estate planning questions at AskHarry.info. To stay current on the Squared Away blog, join our free email list.

Comments are closed.

Let me suggest that more than money family caregivers need training on how to care for their parents or grandparents. For example, what is a safe way to lift someone out of bed? What is the correct way for helping and cleaning people on the toilet?

If we’re gonna give caregivers money, let it be used to train them.