How Did Older Households React to Inflation?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Preserving consumption in the short-term means less resources for the future.

We just released a study that introduces behavioral responses when looking at the effect of inflation on consumption and wealth of near retirees and retirees. The behavioral responses come from a new survey that explores how older households reacted to recent inflation – in terms of labor supply, saving, withdrawals, and asset allocation.

The original study estimated the impact of inflation on the finances of near retirees (head ages 55-62) and retirees (head ages 62 and older) from 2021 to 2025 under alternative macro-economic scenarios, including “Soft Landing” and “Recession.” It focused on two metrics: 1) the real change in consumption from the beginning of the analysis period to the end; and 2) the stock of household wealth (financial and housing) at the end of the period.

The question is how behavioral responses might affect the original findings. Since economic theory is ambiguous on this issue, the authors undertook a new survey fielded by Greenwald Research in November 2023, which included 1,501 respondents ages 55-85. The major responses to inflation involved saving and withdrawals; very few respondents reported changing their labor supply or asset allocation. The results showed that 39 percent of near retirees changed their saving because of inflation. Among those primarily motivated by inflation, annual saving declined by $4,065, on average, or 4 percent of annual household income in 2023. In terms of withdrawals, the results for near retirees and retirees were combined because they are quite similar. Twenty-three percent of respondents changed their withdrawals from 2021 to 2023 because of rising prices. Among those making changes, the average increase was $3,620 (5 percent of 2023 household income).

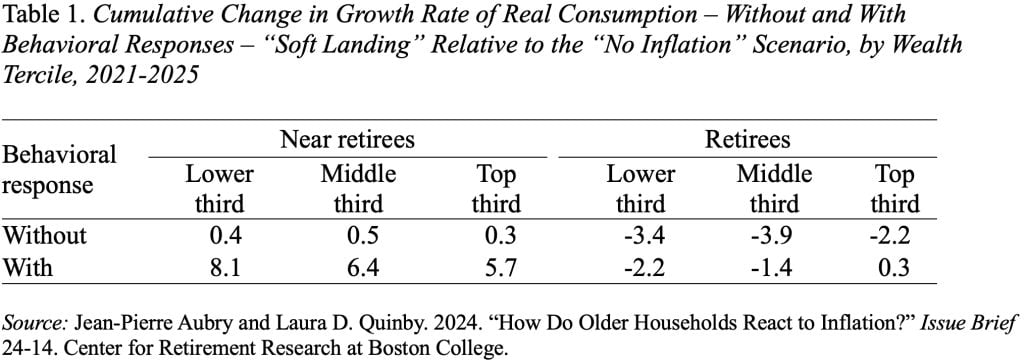

Table 1 shows the difference in the growth rate of real consumption, from 2021 to 2025, for the “Soft Landing” relative to the “No Inflation” scenario without and with behavioral responses. Unsurprisingly, households are able to temporarily boost consumption by tapping into their savings. The key difference in outcomes here is between near retirees – who all show gains in consumption – and retirees – who mainly see small declines.

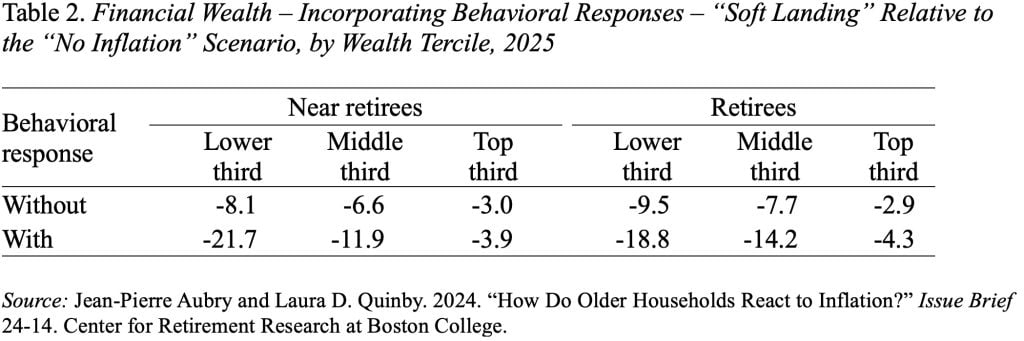

This short-term gain, however, comes at the expense of future consumption (see Table 2). As expected, reduced saving and increased withdrawals compound the direct impact of inflation on wealth.

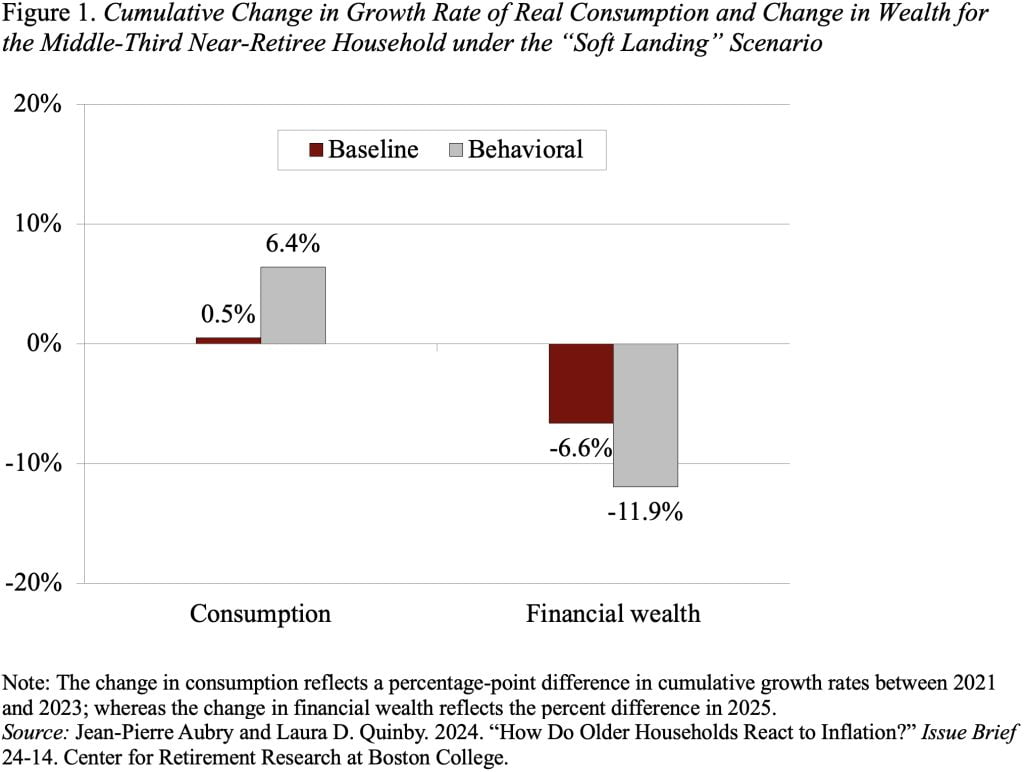

To clearly illustrate this trade-off between current and future consumption, Figure 1 compares the results incorporating the behavioral responses to the original baseline analysis for one type of household: near retirees in the middle-wealth tercile under the “soft landing” scenario. This same trade-off holds across all age groups, wealth terciles, and macroeconomic scenarios.

The question that remains is whether the depletion of assets is permanent or temporary. Will households reverse course as wage gains exceed inflation and budget pressures recede?