How Much Does 401(k) Auto-Enrollment Help Workers Save for Retirement?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

A longer look lowers estimates of its impact, but making saving easy remains essential.

The same research team that documented the impact of auto-enrollment and auto-escalation in 401(k) plans has returned to the topic to assess how real-life events affect the longer-run effect of these automatic provisions. I think it’s really cool for researchers to go back and kick the tires on earlier results. My reading is that the authors still think these automatic provisions are helpful – and they do little harm – but the magnitude of the positive effect on savings is much smaller than they had originally thought.

Some background. As 401(k)s started to replace traditional defined benefit plans in the 1990s, critics noted the burden placed on would-be participants. They had to decide whether or not to join the plan, how much to contribute, how to invest those contributions, how to change asset allocations and their contribution rate as they aged, how to handle accumulations when they changed jobs, and how to draw down investments in retirement. That’s a lot. In response, academic and industry folks tried to figure out how changing plan design could make the process easier and thereby increase participation rates and balances.

The major innovation capitalized on inertia. It involved shifting the enrollment mechanism from opt-in, where employees had to proactively sign up to participate, to opt-out, where employees were automatically enrolled in the plan at a particular contribution rate. In a 2001 study, one member of the “gang” showed that when a large U.S. corporation introduced auto-enrollment the percentage contributing to the plan increased from 37 percent to 86 percent. This effect was much bigger than that from employer matching contributions. Moreover, later work found that it did not depend on the default contribution rate, be it 3 percent or 6 percent. Noticeably, people tend to stick with the default rate.

A lot of this early work contributed to provisions in the Pension Protection Act of 2006, which encouraged automatic enrollment and auto-escalation in the default contribution rate. (The legislation also sanctioned target date funds.) And SECURE 2.0 requires most new 401(k) pans to implement both auto-enrollment and auto-escalation.

While the effect of the auto provisions on participation is clear and robust, the effect on contributions is a little trickier. Auto-enrollment will increase the contribution rate of those who would never have joined the plan and those who would have joined at a lower rate, but will decrease contributions of those who would have contributed more than the default. On average, the studies showed that auto-enrollment increased contributions. This finding raises the question of where the additional contributions come from. Did participants reduce their spending or take on more debt? While a study of new civilian hires in the federal Thrift Savings Plan showed little to no negative credit effects, an analysis of mandatory auto-enrollment in the United Kingdom, with a much larger sample size, found that the positive effect of auto-enrollment on retirement plan saving was partially – about 20 percent – offset by an increase in unsecured debt.

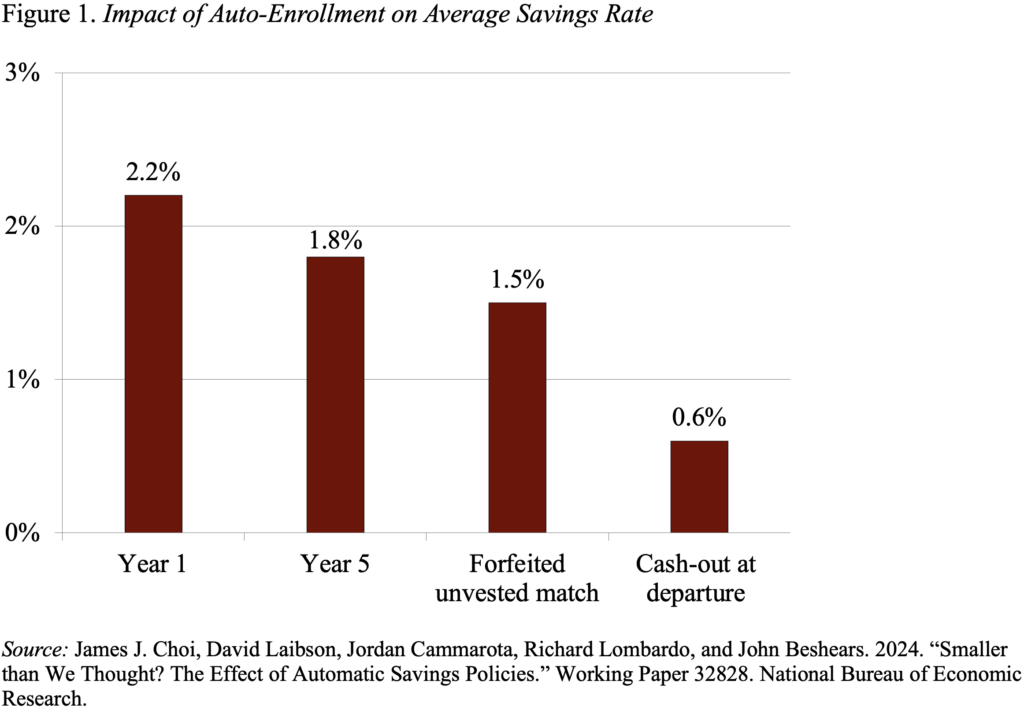

All this is background to the gang’s most recent paper, which looks at other factors – beyond increased debt – that might undermine the positive effect of auto-enrollment. For their sample, the first-year experience suggests that auto-enrollment increased the savings rate by 2.2 percentage points (see Figure 1). (For simplicity, this discussion focuses on auto-enrollment, but incorporating auto-escalation produces a similar pattern.) After five years of employment, however, this percentage drops to 1.8 percentage points, because many individuals not subject to auto-enrollment actively increase their contribution rates, which erodes some of the savings gap. In addition, employee turnover is high, and many leave before their employer matching contributions are fully vested, which further reduces the increment in the saving rate to 1.5 percentage points. Finally, because those automatically enrolled have relatively small balances, their cash-out rate at departure is higher than those who opt in, which further reduces the increment in the saving rate to 0.6 percentage points.

So where does that leave us? Auto-enrollment substantially increases participation and has a positive net effect on saving. And while looking at only the first-year impact overstates the long-term increment to saving, focusing on the real-world complications overstates the negative impact on employee well-being. Indeed, a few thousand dollars may be welcome support for an employee transitioning from one job to another. So even if not perfect, making saving automatic and easy should continue to be our goal.