How Much Do We Spend on Long-Term Care?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Should Medicare long-term expenditures be included or not?

Finding a way to pay for long-term care is one of the major challenges for achieving security in retirement. As long as people are fearful that they will need their money to cover long-term care needs toward the end of life, they will be reluctant to draw down their 401(k) balances or tap home equity. And the need for paid formal care will increase as the baby boom retires with fewer children than earlier generations to provide informal care.

Solving the long-term care problem is really hard, and candidly I cannot get beyond the first step – how to define long-term care expenditures. The issue is whether or not to include a portion of Medicare spending in the tally.

Medicare – the general health insurance program for those 65 and older and the disabled – covers up to 100 days of care in a skilled nursing facility after a participant has spent three days in the hospital. (The patient pays no coinsurance for the first 20 days and $167.50 per day for days 21-100.) In some cases, Medicare will cover home health care. Medicare will also pay for hospice care for people who are terminally ill. Should these expenditures be included in total long-term care expenses?

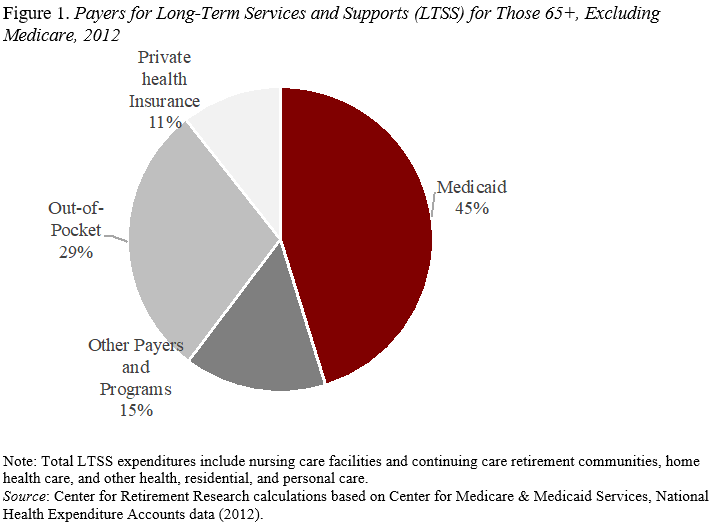

As shown in Figures 1 and 2, excluding or including Medicare provides very different stories. Excluding Medicare long-term care spending – as do, for example, the Kaiser Family Foundation and the 2011 Congressional Commission on Long-term Care – shows a much more substantial role for Medicaid – the means-tested program for low-income individuals. Our Center’s estimates from 2012 federal health care spending data show that Medicaid covered 45 percent of long-term care (see Figure 1). Such support also helps retirees who started out in the middle class but depleted their assets paying for nursing home care and then became eligible for Medicaid.

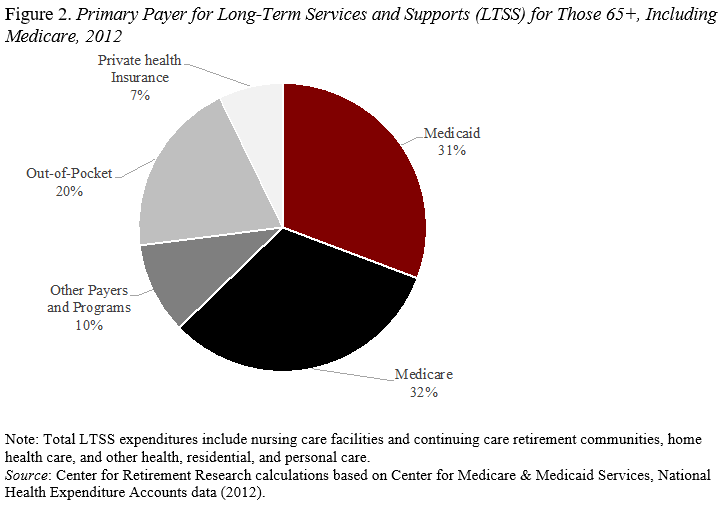

On the other hand, others include the portion of Medicare that pays for the 100 days and some home health services – for example, a 2016 study by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners and a 2015 report by the Congressional Research Service. In this case, our Center’s estimates of the 2012 data show a greatly diminished role for Medicaid (see Figure 2).

The treatment of Medicare payments not only affects the relative role of Medicaid, but it also affects the basic conception of the risk of long-term care. Is it a frequent, relatively short, and inexpensive experience or an infrequent, long, and bankrupting event?