How Much Do You Have to Save for Retirement?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

People often ask how much they have to save for a secure retirement. The answer depends on a number of factors.

- Earnings level. The lower the earnings, the greater the portion provided by Social Security and the lower the individual’s required saving rate.

- Rate of return. The higher the rate of return on assets, the lower the required saving rate.

- Age when saving begins. The earlier the individual starts saving, the lower the required rate for any given retirement age.

- Age of retirement. The later the individual retires, the lower the required rate.

A simple model shows that starting early and working longer are far more effective levers for gaining a secure retirement than earning a higher return. The model takes an 80-percent replacement rate as the goal, assumes Social Security benefits remain as promised under current law, and assumes people draw down 4 percent of their wealth each year. It then calculates the required saving rates for individuals at different earnings levels, at different starting and ending ages, and at different rates of return.

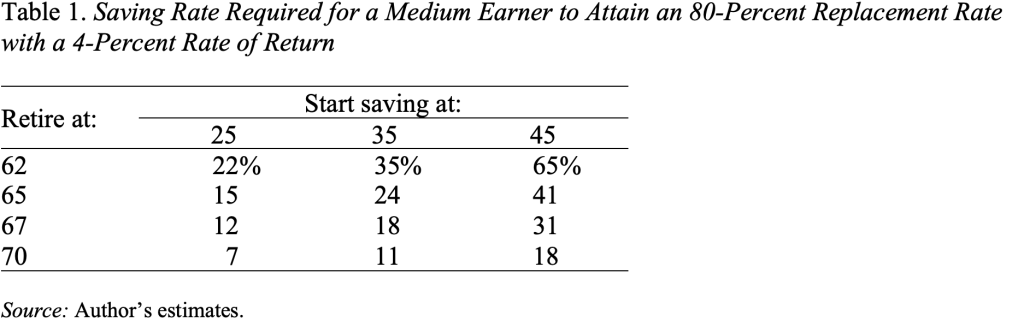

The required saving rates for the medium earner, assuming a rate of return of 4 percent are presented in Table 1. Two messages stand out. First, starting to save at age 25, rather than age 45, cuts the required saving rate by about two thirds. Second, delaying retirement from age 62 to age 70 also reduces the required saving rate by about two thirds. As a result, the individual who starts at 25 and retires at 70 needs to save only 7 percent of earnings, roughly one tenth of the rate required of an individual who starts at 45 and retires at 62 – an impossible 65 percent. But note that even that individual who starts at 45 has a plausible 18 percent required saving rate if he postpones retirement to age 70.

Retiring later is an extremely powerful lever for several reasons. First, because Social Security monthly benefits are actuarially adjusted, they are over 75 percent higher at age 70 than age 62. Second, by postponing retirement people have additional years to contribute to their 401(k) and allow their balances to grow. Finally, a later retirement age means that people have fewer years to support themselves on their accumulated retirement assets.

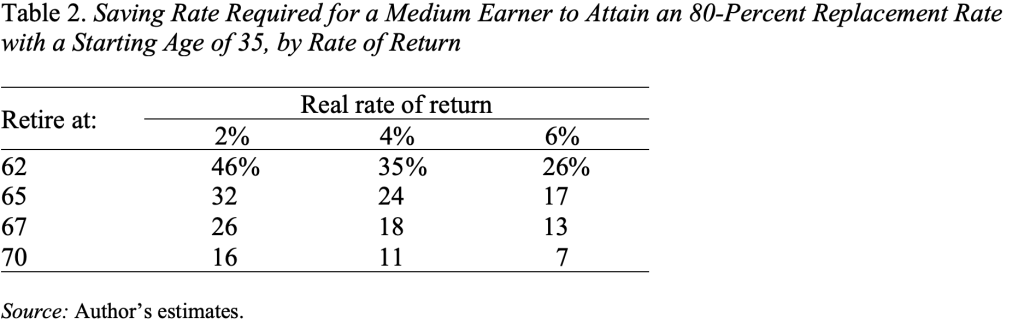

Table 2 shows the impact of lower and higher rates of return for individuals who start at age 35. The 2-percent return is slightly less than the inflation-adjusted long-run rate of return on intermediate-term government bonds and the 6-percent return is slightly less than the inflation-adjusted long-run rate of return on large cap stocks. While higher returns require smaller contribution rates, they also come with increased risk. Even ignoring risk, the required saving differentials are less than those associated with dates for starting to save and the age of retirement. In fact, an individual can offset the impact of a 2-percent return instead of a 6-percent return by retiring at 67 instead of 62.

The story for low earners and maximum earners is essentially the same. The required savings rates differ primarily because of Social Security. Under current law, at age 67 Social Security will replace 55 percent of pre-retirement earnings for low earners and 27 percent of those earning Social Security’s taxable maximum.

It would be easy to assume a different target replacement rate or different levels of Social Security replacement. Such changes are unlikely, however, to alter the basic message: starting early and working longer are far more effective levers for gaining a secure retirement than earning a higher return.