Millennials’ Late Marriage Should Have Only a Minor Effect on Their 401(k) Saving

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Participation and contributions increase slightly after marriage, but impact on holdings at 65 is small.

The Center for Retirement Research just published a second study on how family circumstances affect contributions to 401(k) plans. The first, as reported a few weeks ago, showed that a 401(k) contributor in a two-earner couple with only one saver did not save more to compensate for the fact that his or her spouse did not have a retirement plan at work. The most recent study explores whether the trend toward later marriage will reduce retirement saving by looking at individuals’ contributions to a 401(k) plan before and after marriage.

The most recent study was sparked by the marriage patterns of Millennials, who marry later than previous generations. Since marriage is a major life milestone that often marks a line between youth and adulthood, a logical question is how this delay affects retirement saving.

The answer is unclear. On the one hand, a robust literature has shown that marriage tends to kick-start saving for a house as individuals combine their possessions and make plans for having kids. On the other hand, retirement for young people is so far off in the future that marriage may not necessarily serve as a trigger for retirement saving.

The new study uses data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) – a panel survey on economic and demographic characteristics – to observe individuals both before and after they get married. The analysis follows people for five years: two years before the interview year, the interview year itself, and two years after. Only individuals observed getting married over this period are retained for the analysis.

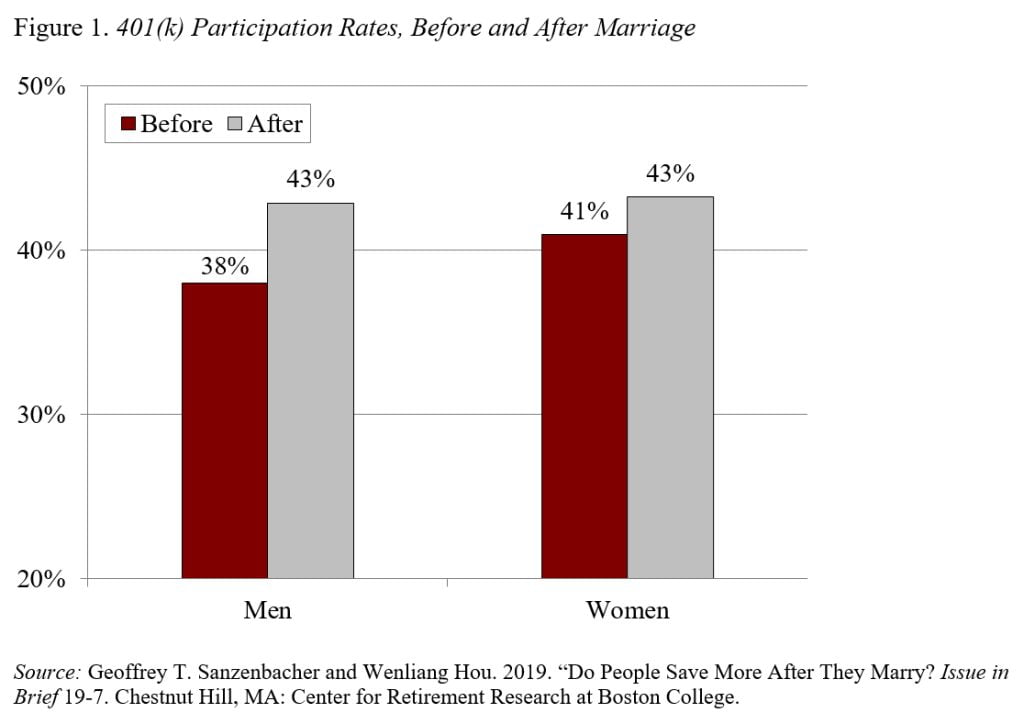

The simple comparison of participation rates before and after marriage – shown in Figure 1 – suggests that both men and women increase their 401(k) participation after marriage.

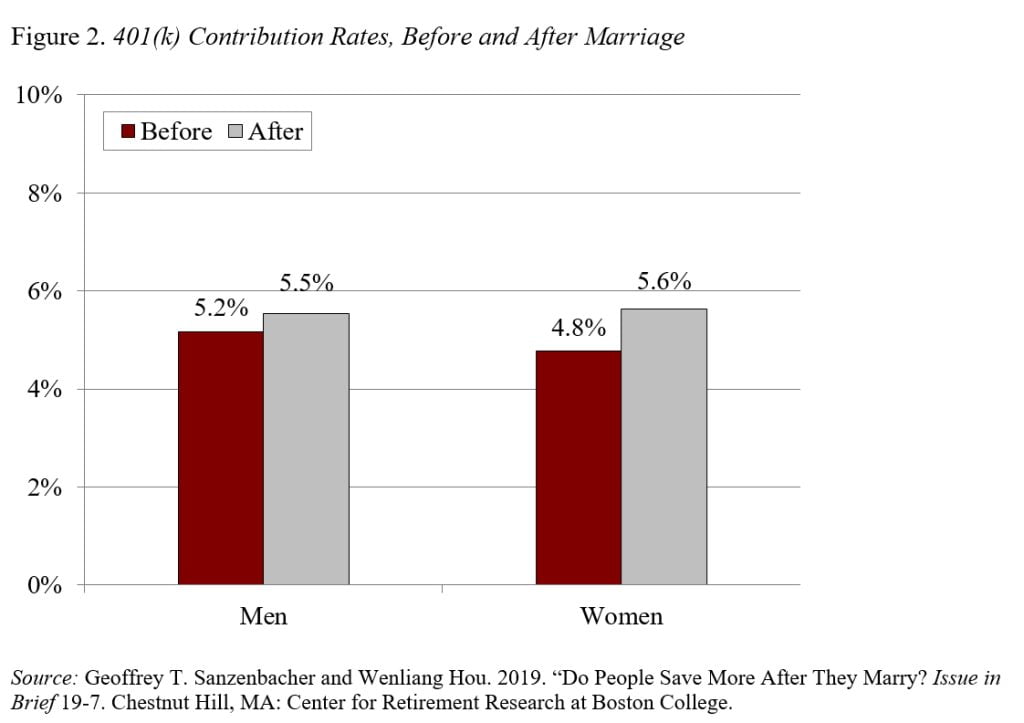

Conditional on participating, contribution rates for men and women increase by 0.3 to 0.8 percentage points, respectively (see Figure 2). These results hold in regressions that control for demographic and educational characteristics.

The important question is what these results mean for 401(k) wealth by age 65. A five-year delay in marriage – the approximate increase observed between Baby Boomers and Millennials – would reduce accumulated assets by 3.1 percent for men and 3.4 percent for women.

So while the delay in marriage may be problematic for some forms of savings – delaying homeownership for example – it seems unlikely to make a large dent in savings through retirement plans.