Most People Think Medicaid Sign-Up Should Be Easier

To help people through the COVID public health emergency, Congress barred the states from removing people from the Medicaid rolls in return for providing additional funding for their programs.

In March, those pandemic-era protections expired and states are returning to the old practice of requiring residents to verify their eligibility to renew the coverage. As a result, many states have begun cutting Medicaid enrollment for reasons ranging from ineligibility to a failure to submit paperwork.

KFF, a health research organization that has been tracking Medicaid enrollment post-pandemic, said that about three out of four people have who have lost their coverage were dropped for procedural reasons, such as not completing their paperwork or missing a deadline.

This is a concern, KFF said, “because many people who are disenrolled for these paperwork reasons may still be eligible.”

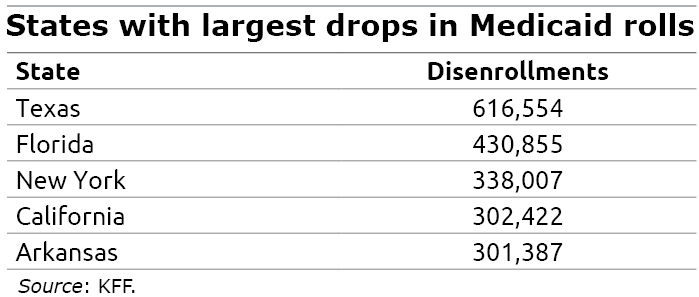

As of Sept. 8, nearly 6 million people had been dropped and KKF estimated earlier this year that perhaps 17 million Americans, including 5 million children, could eventually lose their insurance – an 18 percent decline from pandemic levels.

This is a case of reality not lining up with public opinion. Two-thirds of Americans surveyed in late 2022 and early this year said governments should take a variety of steps to reduce the burden on individuals to get or keep their Medicaid coverage.

“When given a choice, Americans prefer to see governments take action to make the safety net more accessible, and they do so in an overwhelming fashion,” the researchers in a Health Affairs study concluded.

In Texas, more than 600,000 people who had Medicaid during the pandemic have lost their coverage. During COVID, the continuous enrollment provision in Congress’ relief package had increased Medicaid enrollment in Texas and elsewhere because all of the existing enrollees were staying in the program at the same time as new enrollees were signing up.

Some people are losing their Medicaid coverage now because they are no longer eligible. In the best situations, some were dropped because they’ve have gotten a better job with employer health insurance. In other cases, someone who is earning more in a strong job market no longer qualifies due to the program’s earnings cap.

However, people who are still eligible for Medicaid may not know that they have to re-enroll to keep the benefit, or they are daunted by a complex renewal process.

Policies that provide government benefits aren’t always structured to encourage maximum enrollment. The application process can create administrative barriers to enrollment or renewals. The new survey, by Texas A&M University and Georgetown researchers, asked individuals about nine specific policies to make enrollment easier, including automatic renewals of Medicaid coverage, improving government outreach to potential enrollees and people who’ve been dropped, and shifting more of the burden from individuals to state agencies to ensure that people who are eligible are being covered.

A majority of people were in favor of all nine policies, though they split along predictably partisan lines. Conservatives were slightly less in favor, supporting six of the proposed steps to ease enrollment, compared with eight for liberals. People who had personal experiences with Medicaid were more supportive of the extra efforts. People whose survey responses indicated racial prejudices were less supportive, even though a substantial share – 40 percent – of Medicaid enrollees are White.

Despite the divisions, “there is strong support for state actions that ease administrative burdens rather than return to a more onerous status quo,” the researchers concluded.

Squared Away writer Kim Blanton invites you to follow us on Twitter @SquaredAwayBC. To stay current on our blog, please join our free email list. You’ll receive just one email each week – with links to the two new posts for that week – when you sign up here. This blog is supported by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.