New Study on Leakages Narrows the Range of Estimates

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Leakages probably reduce age 60 balances by 30 percent. Is that bad or good?

Researchers from the Treasury and Congress’ Joint Committee on Taxation have provided new estimates of how much money “leaks” out of 401(k)s and IRAs based on restricted tax data. It’s a welcome addition to the literature because the existing range of estimates is enormous.

Leakages come from three sources – cashouts when participants change jobs, hardship withdrawals, and the failure to repay loans. The government has attempted to discourage leakages by generally imposing a 10-percent penalty – in addition to regular income taxes – on withdrawals before age 59½. Employers are also required to withhold 20 percent of any distributions paid directly to recipients. Nevertheless, considerable money still leaks out. The question is how much.

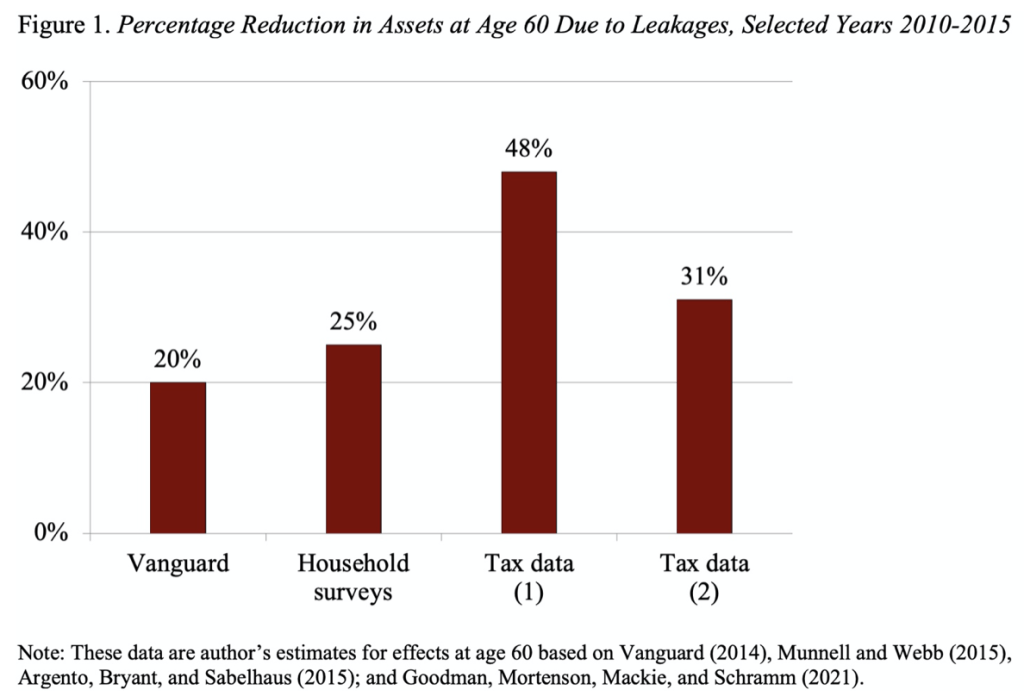

Up to now, we have had three sets of estimates on leakages, from research conducted in the 2010-2015 period. The first is data from Vanguard, which suggest that approximately 1.2 percent of assets leak out each year. This number is probably an underestimate because Vanguard plans tend to be relatively larger with higher-paid employees, who have less need to withdraw their funds. The second set of estimates, which are based on data from household surveys, indicates that roughly 1.5 percent of money leaks out each year. The third comes from a 2015 study, which – like the new study – is based on tax data; it suggests that leakages amounted to 2.9 percent of assets each year. These three estimates would reduce the 401(k)/IRA wealth at age 60 by 20 percent, 25 percent, or 48 percent, respectively (see Figure 1). An enormous range!

For the record, I have always gravitated toward the conclusion that leakages reduce age 60 balances by 25 percent. But because the study indicating a 48-percent reduction is based on official tax data, it has garnered quite a following. The reason why the new study is so important is that it also uses restricted tax data. The new study, however, comes to a much different conclusion – suggesting that age-60 balances are reduced by 31 percent (see Figure 1).

The authors of the new study offer three reasons for the difference between their results and the previous study based on tax data: 1) they defined leakages more narrowly, excluding distributions from defined benefit plans and those on account of disability or death; 2) their contribution numbers came from third parties rather than household survey data; and 3) they netted within-year contributions and distributions. Those seem like good decisions to me. So, I’m moving my estimate from a 25-percent to a 31-percent reduction at age 60.

The bigger question is how to think about leakages. They’re not all bad. First, research has shown that the ability to access funds encourages people to participate in 401(k) plans and to make larger contributions. Second, early withdrawals allow people to smooth over financial shocks, which is also a good thing. But leakages do reduce balances at retirement, so we want to make sure that withdrawals are indeed used to smooth consumption and people are not simply cashing out because it is freaking impossible to move money from one 401(k) plan to another.