Nursing Homes are Far Short of New Staff Requirements

Workers in the nation’s nursing homes have the inside story, and the staff shortages they describe are not pretty.

“Lack of enough staff has put many of my residents at risk for falls, bed sores, and much more,” said a certified nurse’s aide with 20 years of experience, who wrote in support of new federal regulations that set minimum staffing levels.

“I truly feel horrible for the [residents] when they have to wait for sometimes over an hour just to get assistance because everybody is so busy,” said another worker.

In response to the high death toll in nursing homes during COVID, the Biden administration followed through on its promise to “crack down on nursing homes that endanger resident safety.” Last month, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) finalized new minimums for staff levels in nursing homes, where more than 1 million Americans currently live. The standards will go into effect over the next five years.

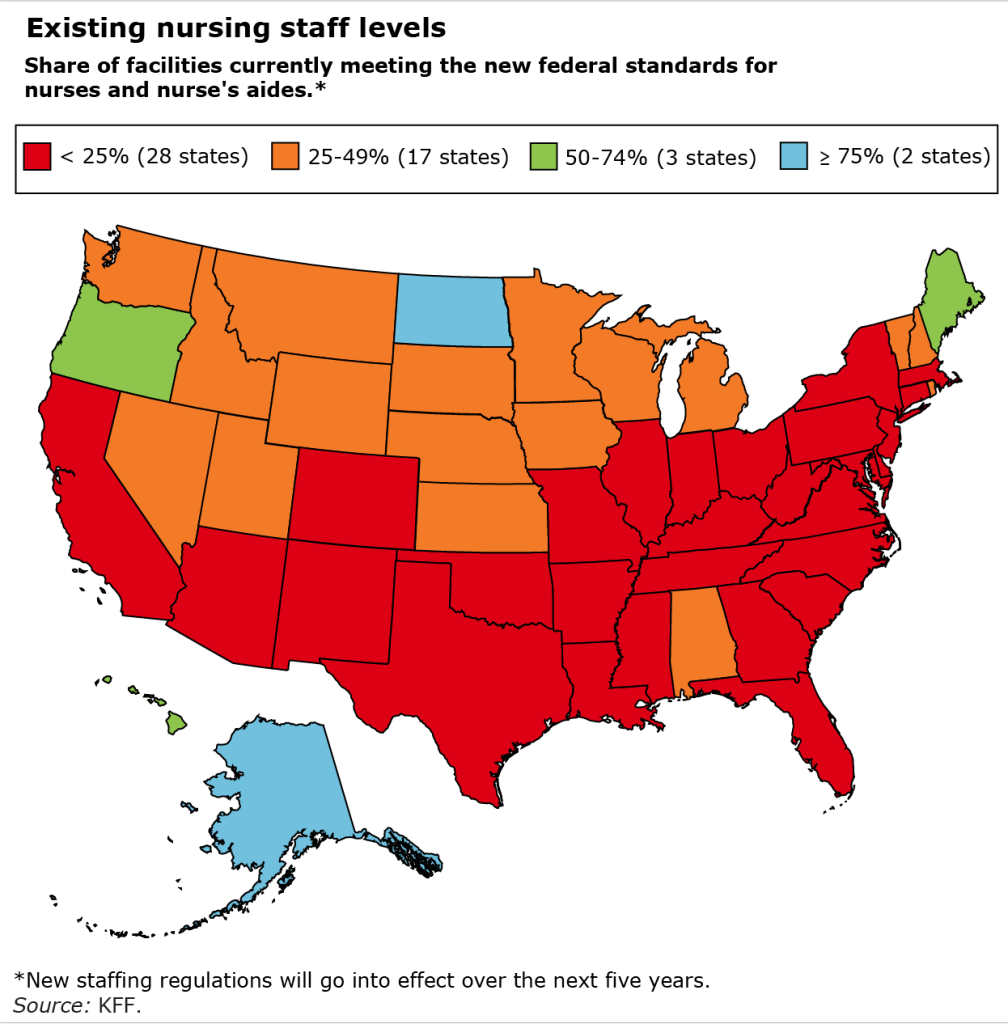

With U.S. unemployment at a rock-bottom 4 percent and staff turnover already high, it will be extremely difficult for nursing home operators to hire more nurse’s aides, registered nurses, and licensed practical nurses to meet the new minimums. In over half the states, fewer than one out of four nursing homes currently have enough staff to meet all three of CMS’ staffing requirements, according to a tally by KFF, a health care policy, research and news organization.

But nursing homes have more leeway currently to increase staffing, according to a recent study of the industry’s finances. The researchers said the industry is “substantially more profitable than it appears.” They estimated that “63% of nursing home profits were hidden” through a strategy called “tunneling,” in which some facility owners “extract profit by making inflated payments for goods and services” they provide through companies they also control. Nursing home operators respond that their staffing levels are determined by inadequate funding by Medicaid, which is their primary source of revenue.

In any case, hiring more nursing staff in an already tight labor market will be likely to drive up the workers’ wages, and threatens to increase the already high cost of care. Some in the industry argue this will force some facilities to close. The requirements are “unfathomable” said Mark Parkinson, president of the industry group, the American Health Care Association.

In a nursing home with 100 residents, the Biden administration estimates the new standards would translate to two or three registered nurses, at least 10 nurse’s aides, and two staff who are either registered nurses, licensed professional nurses, or nurse’s aides.

In recognition of the difficulty nursing homes face, CMS will introduce the new requirements in phases. In the first set of standards, each facility must have a registered nurse on duty 24 hours a day, and each resident must receive care from aides or nurses for nearly 3.5 hours per day. This regulation will go into effect in 2026 for urban facilities and in 2027 in rural areas, which have fewer available workers, including fewer of the immigrants who often fill these low-paying jobs.

In the next phase, the requirements get more specific. Nursing homes must provide each resident with just over 30 minutes a day of attention from a registered nurse and about 2.5 hours of daily care by nurse’s aides. Nursing homes can decide which type of nursing staff they will use to fill in the additional half hour required to meet the previous standard of nearly 3.5-hours-per day for all types of care. These standards go into effect in 2027 in urban areas and in 2029 in rural areas.

KFF’s report also broke down the staffing requirements in various states and by type of facility:

- Only 11 percent of for-profit nursing homes currently meet the three minimum staffing requirements, compared with about 40 percent of non-profit and government facilities.

- Less than one in four nursing homes in most of the largest states – California, Florida, Illinois, Ohio, and Texas – meet the requirements.

- The share of facilities meeting them range from 5 percent or less in Arkansas, Tennessee, Texas and Louisiana to more than 50 percent in Alaska, the District of Columbia, Hawaii, Maine, North Dakota, and Oregon.

COVID exposed the failings of nursing homes. But solving the staff shortages at the heart of many of their problems will be very challenging.

Squared Away writer Kim Blanton invites you to follow us @SquaredAwayBC on X, formerly known as Twitter. To stay current on our blog, join our free email list. You’ll receive just one email each week – with links to the two new posts for that week – when you sign up here. This blog is supported by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.