Older People Are Trying to Work Longer

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

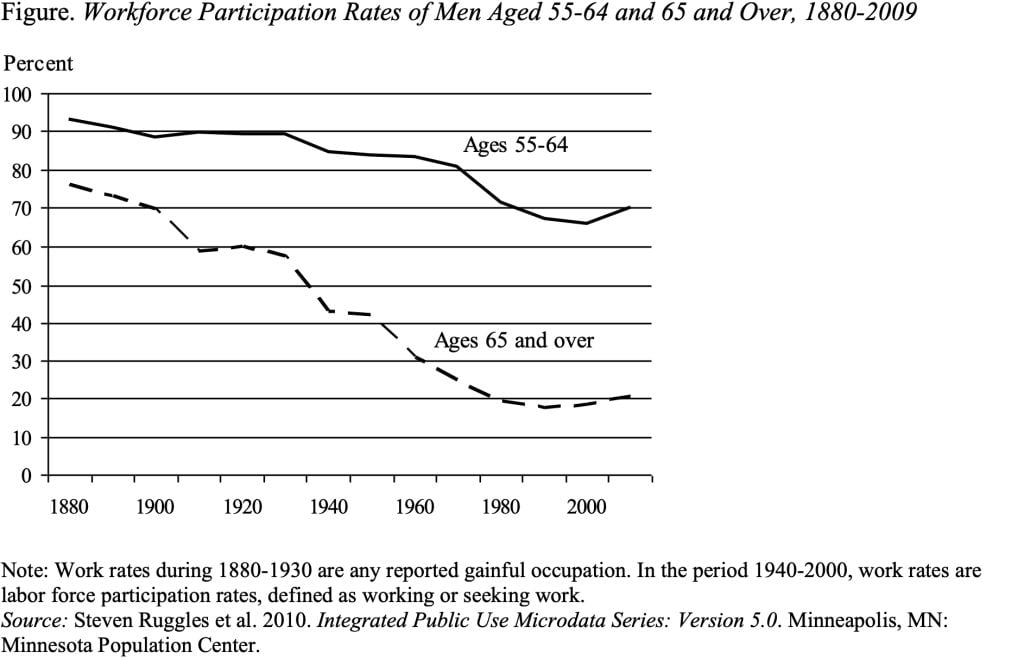

Since working longer is the key to a secure retirement for the vast majority of older Americans, it’s useful to take a look at labor force trends for men under and over 65 for the last century or so. (The focus is on men because women’s patterns reflect both their increasing labor force participation over time as well as their shifting retirement behavior.)

The notion of retirement as a distinct and extended stage of life is a recent innovation. Up to the end of the 19th century, people generally worked as long as they could. At the end of the 19th century, an unexpected and substantial stream of income appeared in the form of old-age pensions for Civil War veterans that allowed people to stop working. For a variety of reasons, work rates did not return to their previous levels as the veterans died off. The next big decline in the work rates of older people occurred after World War II. One obvious factor was the availability of Social Security benefits and the expansion of employer pensions. The introduction of Medicare in 1965 and the sharp increase in Social Security benefits in 1972 probably led to the final leg of the decline in workforce activity of older men. And because benefits were available at 62, Social Security may also explain part of the decline in labor force activity for men 55-64.

The downward trajectory stopped around 1990, and since then the labor force participation of men both 55-64 and 65 and over has gradually increased. Many factors help explain this turnaround.

- Social Security: Changes to Social Security made work more attractive relative to retirement. The liberalization and, for some, the elimination of the earnings test removed what many saw as an impediment to continued work. The delayed retirement credit, which increases monthly benefits for each year that claiming is delayed between the Full Retirement Age and 70, has also improved incentives to keep working.

- Pension type: The shift from defined benefit to 401(k) plans eliminated built-in incentives to retire. Studies show that workers covered by 401(k) plans retire a year or two later on average than similarly situated workers covered by a defined benefit plan.

- Education: People with more education work longer than those with less. Over the last thirty years education levels have increased significantly, and the movement of large numbers of men up the educational ladder helps explain the increase in participation rates of older men.

- Improved health and longevity. Life expectancy for men at 65 has increased about 3.5 years since 1980, and much of the evidence suggests that people are healthier as well. The correlation between health and labor force activity is very strong.

- Less physically demanding jobs: With the shift away from manufacturing, jobs now involve more knowledge-based activities, which put less strain on older bodies.

- Joint decisionmaking. More women are working, wives on average are three years younger than their husband, and husbands and wives like to coordinate their retirement. If wives wait until age 62 to retire so that they qualify for Social Security, that pattern would push husbands’ retirement age towards 65.

- Decline of retiree health insurance. Combine the decline of employer-provided retiree health insurance with the rapid rise in health care costs, and workers have a strong incentive to keep working and maintain their employer’s health coverage until they qualify for Medicare at 65.

- Non-pecuniary factors. Older workers tend to be among the more educated, the healthiest, and the wealthiest. Their wages are lower than those earned by their younger counterparts and lower than their own past earnings. This pattern suggests that money may not be the only motivator.

Will the increase in labor force participation continue? The fact that all the incentives associated with the recent reversal remain in place argues for “yes.” But there are risks – the move away from career employment, the availability of Social Security at 62, and employer resistance to part-time employment. More on the risks later.