Older Workers Face Two Forces

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Although the economy is technically in a recovery, unemployment remains high. And the Fed’s August 9 decision to keep rates low through mid-2013 suggests that policymakers expect weak growth for the foreseeable future. What’s happening to older workers in this never-ending malaise?

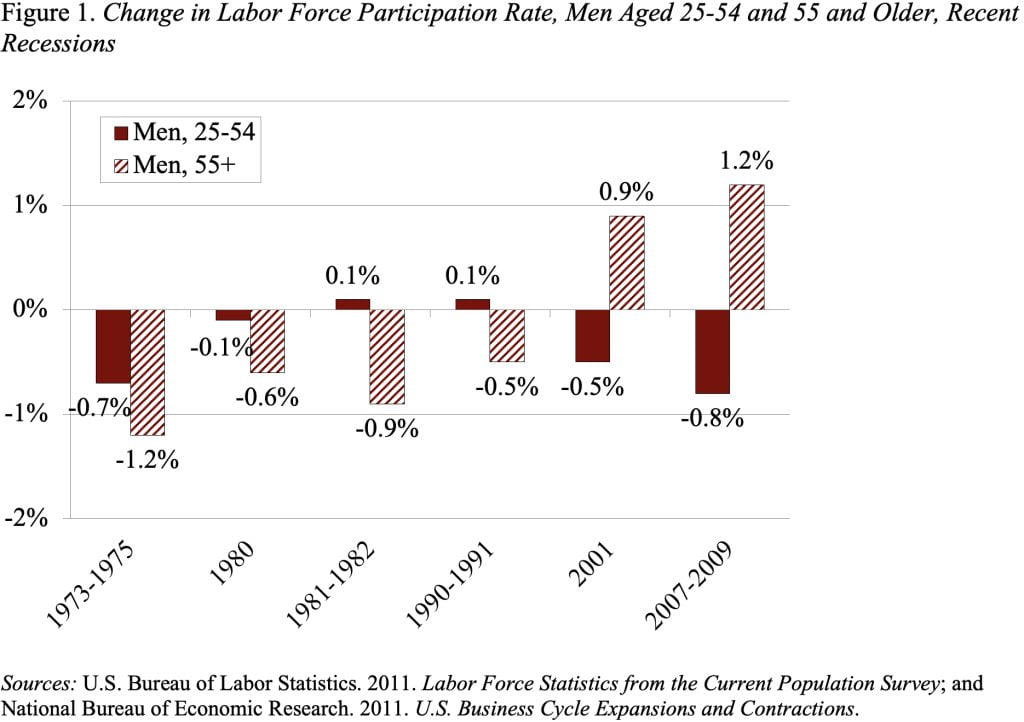

The answer turns out to be a little complicated. Two forces are at work. On the one hand, labor force participation among older workers has risen significantly since the mid-1980s, a reversal of the long-standing trend toward ever-earlier retirement. The reasons for this reversal include changing incentives in Social Security and employer pensions; better education and health coupled with less strenuous jobs; and the decline in retiree health insurance. Participation rates among older men even continued to rise during both of the recessions in this decade – a dramatic change from previous experience (see Figure 1). Most likely the upward trend was reinforced by the financial crises that depleted 401(k) balances

On the other hand, the edge that older workers used to have relative to younger workers when it comes to layoffs seems to have disappeared. The conventional wisdom was that when workers are young, they and their employers share the costs of acquiring skills that are particularly useful at the particular firm. When workers age, employers are reluctant to lay them off because they would lose their investment and be forced to train new younger workers. Until recently, virtually every study looking at displacement rates concluded that the probability of being displaced declines with age. But things are changing. Data from the Displaced Worker Survey show that the difference in displacement rates between younger and older workers has disappeared. The key factor explaining this loss of relative job security is a decline in the tenure of older workers as workers increasingly shift jobs in their 50s. It was long tenure, not age, that had been protecting older workers from being laid off.

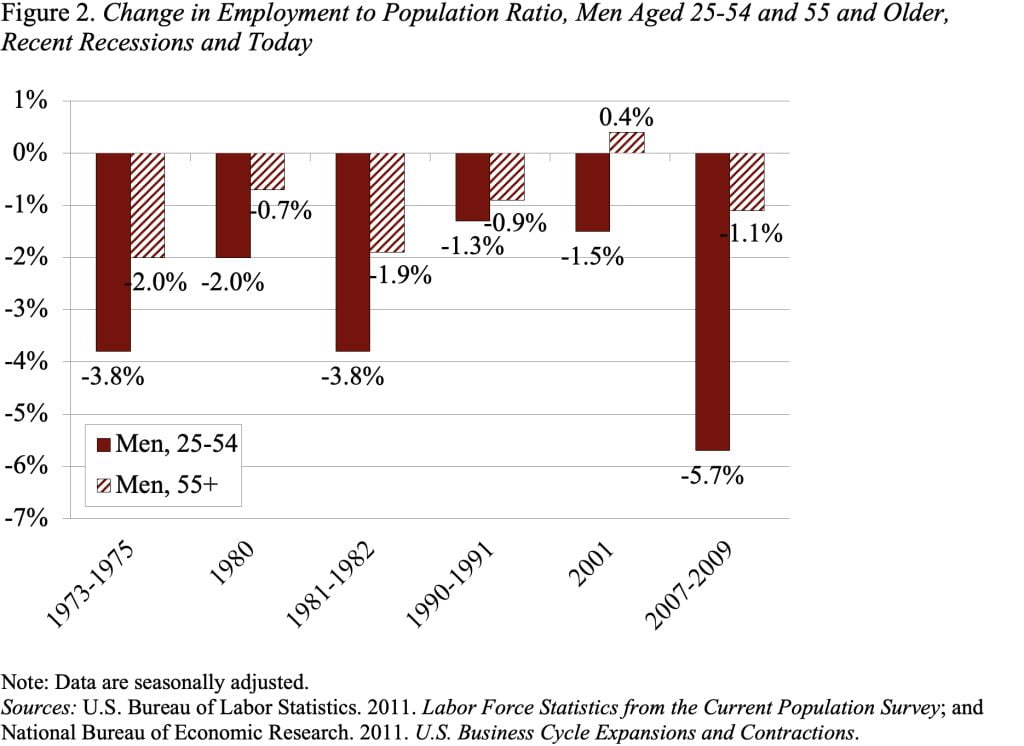

Of the two forces, the trend growth in labor force participation appears to dominate the loss of job security. As a result, the employment rate of older workers – the percent of the population with a job – declined only slightly during the 2007-2009 recession. This pattern contrasts sharply with the far more typical decline in employment rates for workers under age 55 (see Figure 2).

Not all is well, however. The number of older people who want to work is much greater than the number of available jobs. As a result, the unemployment rate for older workers has increased more than in any previous post-war recession. And older workers who lose their jobs have a very hard time finding a new one.