People with Disabilities Were More Cautious in COVID

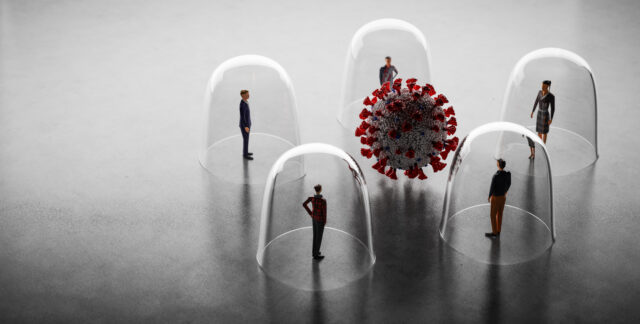

Although no one was left untouched by COVID’s devastation, people with disabilities engaged in cautious behaviors far longer than people without disabilities, according to Mathematica research contrasting the shift in attitudes about the pandemic over time.

Earlier studies by other researchers have shown that people with disabilities who contracted COVID had higher rates of hospitalization and mortality than people without disabilities. Americans with intellectual disabilities had the second-highest COVID death rate, after the elderly, among those who were hospitalized. If they had developmental disabilities, cerebral palsy, or Down syndrome, comorbid medical conditions made them more susceptible to COVID-related mortality. People with any type of disability had longer hospital stays, and their risk of readmission was higher.

In 2020, most people took extraordinary steps to protect their health. Seniors went to the grocery store early in the morning to beat the crowds, and some people even quit their jobs or relocated to less populous areas rather than risk getting sick. The Mathematica researchers found that people with disabilities had higher perceived chances of infection than people without disabilities.

Americans finally began to venture out when vaccines became available in 2021. But although people with and without disabilities reported a similar likelihood of getting the vaccine, the researchers found that people with disabilities resisted making adjustments to the reduced risks. The share who exhibited uncertainty over how to keep themselves protected from COVID-19 was also larger than in the general population, and that uncertainty rose over time.

One example in the study came from a survey question asking if they’d recently attended a gathering of more than 10 people. One month after the pandemic started, roughly 2 percent of people with and without disabilities said they had. A year later, in the midst of the vaccine rollout, 14 percent of people with disabilities had attended these large gatherings, compared with 23 percent of people without disabilities.

The study also documented significant differences in COVID’s financial impact. The relief checks approved by Congress in 2020 and again in 2021 were lifesavers for millions of workers who were laid off or furloughed for indefinite periods of time.

People with disabilities got these checks at higher rates than others. But if they were laid off, they were less likely to apply for and receive unemployment benefits in 2020. As a result, people with disabilities reported financial hardship at a higher rate throughout COVID. One in four were afraid they would run out of money – double the rate for people without disabilities.

The adaptations that all Americans made to the pandemic were extraordinary. But it took longer for people with disabilities to change their behavior in 2021.

The differences in the attitudes and behaviors between people with and without disabilities “persisted, and in some cases, even expanded, as the pandemic evolved,” the researchers concluded.

To read this study by Amal Harrati, Marisa Shenk, and Bernadette Hicks, see “Experiences, Behaviors, and Attitudes about COVID-19 for People with Disabilities Over Time.”

The research reported herein was derived in whole or in part from research activities performed pursuant to a grant from the U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA) funded as part of the Retirement and Disability Research Consortium. The opinions and conclusions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent the opinions or policy of SSA, any agency of the federal government, or Boston College. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, make any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of the contents of this report. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply endorsement, recommendation or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof.