Rough Waters Ahead

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Everyone wants financial security once they stop working. Americans weaned on post-war affluence have come to expect an extended period of leisure at the end of their work life. And, indeed, the majority of today’s retirees are able to afford a decent retirement. However, this group is living in a “golden age” that will fade as Baby Boomers and Generation Xers reach traditional retirement ages in the coming decades.

This gloomy forecast is due to the changing retirement income landscape. Today’s workers will be retiring in a substantially different environment than their parents did. The length of retirement is increasing as the average retirement age hovers at 64 for men and 63 for women while life expectancy continues to rise. At the same time, replacement rates – retirement benefits as a percent of pre-retirement earnings – are falling for a number of reasons.

First, at any given retirement age, Social Security benefits will replace a smaller fraction of pre-retirement earnings as the Full Retirement Age rises from 65 to 67. Second, while the share of the workforce covered by a pension has not changed over the last quarter of a century, the type of coverage has shifted from defined benefit plans, where workers receive a life annuity based on years of service and final salary, to 401(k) plans, where individuals are responsible for their own saving. In theory 401(k) plans could provide adequate retirement income, but individuals make mistakes at every step along the way and the median balance for household heads approaching retirement is only $78,000. Third, most of the working-age population saves virtually nothing outside of their employer-sponsored pension plan.

In addition to a rising period of retirement and falling replacement rates, out-of-pocket health costs are projected to consume an ever greater proportion of retirement income. And asset returns in general, and bond yields in particular, have declined over the past two decades so a given accumulation of retirement assets will yield less income.

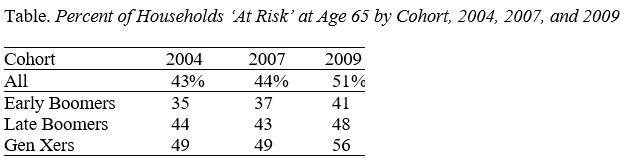

To quantify the impact of the retirement security crunch, the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College developed the National Retirement Risk Index. The Index measures the share of working American households who are ‘at risk’ of being unable to maintain their pre-retirement standard of living in retirement. The results for 2004, 2007, and 2009 are shown in the table. Even before the financial crisis, almost 45 percent of working households were projected to be ‘at risk’; after the crisis, this level increased to 51 percent.

Moreover, the percent ‘at risk’ increases with each cohort. Late Boomers show more households ‘at risk’ than Early Boomers, and Generation Xers have even larger numbers ‘at risk.’ This pattern reflects increasing longevity combined with the continued shift to 401(k) plans and declining Social Security replacement rates.

It is important to note that the Index is based on very conservative assumptions. Everyone is assumed to retire at 65; they don’t, they retire earlier. Everyone is assumed to tap the equity in their home through a reverse mortgage; only a fraction of those eligible elects this option. All financial assets are assumed to be annutized so that retirees gain the maximum income from their assets; in fact, annuitization is rare. In short, the NRRI probably understates the challenges ahead.