Should We Make 401(k) Automatic Provisions Automatic?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Given the large gap between retirement needs and resources, we should ensure that the retirement programs we have work as well as possible. In the private sector, the main retirement program is 401(k) plans. These plans are not working as well as they could – a problem that could be remedied with more extensive use of automatic provisions. Maybe the government should mandate automatic enrollment and automatic escalation in the default contribution rate.

When 401(k) plans began in the early 1980s, they were viewed mainly as supplements to traditional defined benefit plans. Since 401(k) participants were presumed to have their basic retirement income security needs covered, they were given substantial discretion over 401(k) choices, including whether to participate, how much to contribute, how to invest, and when and in what form to withdraw the funds. Today most workers have a 401(k) as their primary or only plan, but these plans still operate under the old rules.

The problem is that many people, left to their own devices, make bad decisions with respect to 401(k) plans. The most basic mistake is the failure to join the plan.

The good news is that behavioral economists have demonstrated the importance of inertia in participation decisions. Studies have shown that requiring workers to “opt out” of a plan rather than the traditional requirement to “opt in” can significantly increase participation rates. Policymakers bought this evidence and passed the Pension Protection Act of 2006, which removed obstacles and provided incentives for companies to add automatic enrollment to their plans.

The legislation also recognized that automatic enrollment alone does not result in adequate 401(k) savings. The inertia that makes the approach effective for participation can lock people into low levels of contributions. That is, the typical default contribution rate is 3 percent, and, left on their own, people would tend to stay at this level. To combat this problem, the legislation encouraged automatic increases in the default deferral percentage.

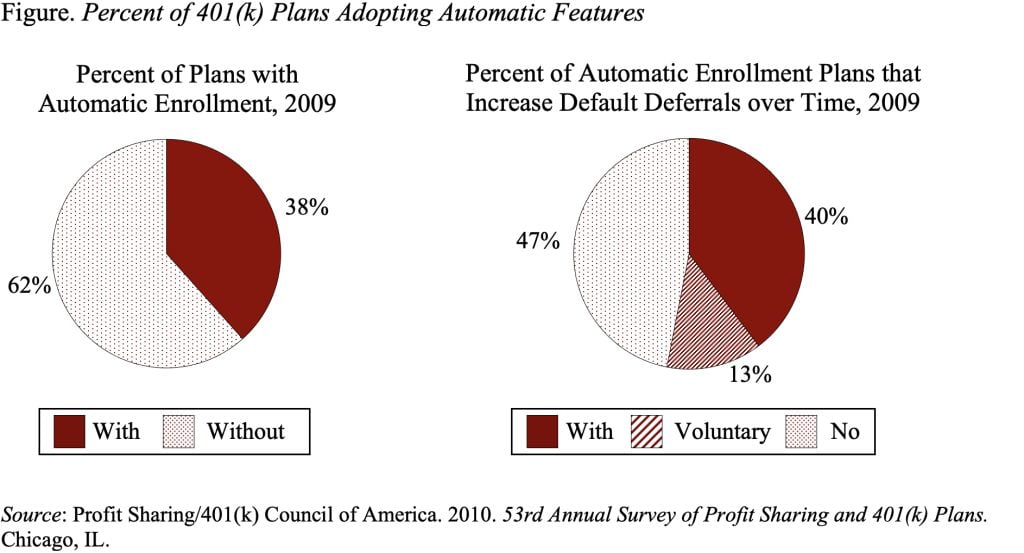

Despite the evidence and the legislative boost, surveys have found that no more than 40 percent of plans offer automatic enrollment (see Figure); and the vast majority of plans apply the provisions only to new hires. Equally important, only 40 percent of firms with automatic enrollment offer automatic escalation in the default deferral rate. The reason for the slow pace of adoption of automatic provisions may be that boards of directors only see the cost of the employer match for additional employees and not the benefits to the firm of additional retirement saving.

The fact that many companies are not taking advantage of the available tools to increase participation and contributions means that 401(k) plans are not working as well as they could. The answer may be to make automatic provisions an integral part of 401(k) plans. That is, the time may have come to make the automatic provisions automatic.