Social Security and Two-Income Couples

The decades-long march of women into the nation’s workplaces may be the most enduring trend in the labor force – and a signature of American progress.

But it is also one more reason that Social Security benefits today replace a smaller share of the lifetime earnings of married couples than they did in the past, when far fewer women worked for pay.

Other reasons include the gradual increase in the age at which U.S. workers can claim their full retirement benefits, from age 65 for the oldest retirees to 67 for Generation X. Medicare premiums are also taking more out of the monthly Social Security check, and more retirees are being taxed on a portion of their benefits over time.

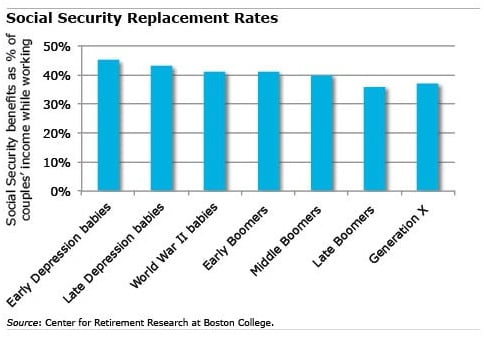

But for married couples, the sharp increase in the ranks of working wives has reduced the share of their joint earnings during their working years that is replaced by Social Security when they retire. For the typical couple born in the Depression, Social Security benefits cover 45 percent of their prior earnings, but that falls to 41 percent for baby boomer couples retiring today, according to new research by the Center for Retirement Research, which supports this blog.

These Social Security “replacement rates” – benefits as a percent of employment earnings – will continue to decline, to just 37 percent for Generation X couples born between 1966 and 1975.

These Social Security “replacement rates” – benefits as a percent of employment earnings – will continue to decline, to just 37 percent for Generation X couples born between 1966 and 1975.

The federal government uses the same formula to calculate Social Security benefits for every man and woman who works. The reason replacement rates are lower for two-income households hinges on something called the “spousal benefit,” which is paid even to wives who never held a job outside the home.

To understand how this works, compare three retired couples. The Smiths are a traditional couple: he worked, and she did not. But Mrs. Smith receives a Social Security check each month that is equal to half of her husband’s check – that’s how spousal benefits were designed under 1939 amendments to the Social Security Act.

In contrast, the Williams both had jobs. His employment earnings were the same as Mr. Smith’s, and so are his Social Security benefits. Mrs. Williams earned one-quarter of what her husband made. Under the rules, Social Security increases the modest monthly benefit based on her own work history to the level of the spousal benefit – so she receives the same amount in her check as the non-working Mrs. Smith. But since the Williams together brought home more money in their paychecks, their combined Social Security checks – which equal the Smiths’ – replace less of the Williams’ higher earnings.

In the third couple, Mrs. Jacobs not only worked but she earned what her husband did. Her Social Security benefit is based on her own employment history, and it’s the same as her husband’s. But the incremental increase in her own benefit – above the spousal benefit that non-working or low-paid wives receive – isn’t enough to make up for Mrs. Jacobs’ major contribution to the household’s higher earnings. So the Jacobs’ replacement rate is even lower than it is for the other two couples.

The other factors – gradual increases in the full retirement age, rising Medicare premiums, and more retirees being taxed – are also eroding how much married couples receive from Social Security.

But the steady march of women into the labor force remains important.

Full disclosure: The research cited in this post was funded by a grant from the U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA) through the Retirement Research Consortium, which also funds this blog. The opinions and conclusions expressed are solely those of the blog’s author and do not represent the opinions or policy of SSA or any agency of the federal government.

Comments are closed.

The reduced percentage of earnings you mentioned – even considering those “other factors” – should be (at least partially) offset by the different mortality rates of the different demographic groups and the longer life expectancies of higher income individuals.

I read elsewhere that the Social Security benefit distribution formula was intentionally designed to replace a greater fraction of the lifetime earnings of low earners than of high earners, and that it was simply a method of redistributing wealth to lower income groups. (If true, then it makes sense that dual-income households would receive a smaller percentage benefit in return.)

(But, I certainly wouldn’t step into the minefield that it was women entering the workforce that caused this…)

Social Security is a tax, not an IRA. The reason an unemployed spouse gets any benefit at all is because some others paid more than she did (which was nothing.) This is not news to anyone.

Full SSA benefits at age 67 is not just for Gen Xers, but for late boomers as well. I was born in ’62, and I also don’t get full benefits until age 67. (That’s as of now – they can always raise the age yet again, and they likely will.)

‘Tis a small point, and not the focus of the article, but you should get it right.