Social Security Benefits Will Increase by 1.3 Percent in 2021

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

A modest increase reignites the debate over the appropriate price index.

How best to keep Social Security benefits up to date with inflation has been a controversial issue. Critics have argued for decades that the CPI-W understates the inflation of the elderly because it does not reflect how large a share of their budget goes for medical care, where prices have been rising rapidly. The elderly also tend to be hurt by the introduction of new consumer technology because they consume relatively less of these goods and do not benefit as much as the rest of the population from the initial declines in prices.

Two things made me want to look again at the Social Security price index. First, the government just announced that Social Security benefits will increase by 1.3 percent for 2021, a woefully inadequate increase according to some commentators. Second, Joe Biden’s plan for Social Security – as well as congressional Democrats’ proposed “Social Security 2100 Act” – include changing the index used for adjusting Social Security benefits.

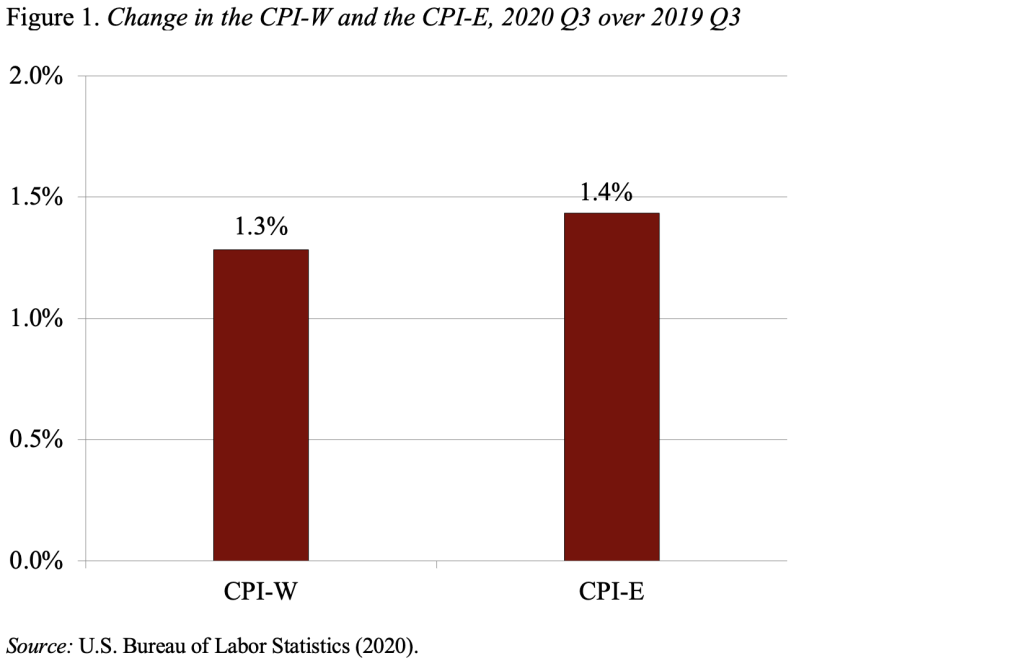

Social Security benefits are adjusted each year based on the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W). The adjustment for 2021 is based on the increase in the CPI-W for the third quarter of 2020 over the third quarter of 2019 – producing a 1.3 percent increase (see Figure 1).

A modest increase tends to reignite the debate over whether the government is using the most appropriate index to adjust Social Security benefits. To address this issue, Congress in 1987 directed the Bureau of Labor Statistics to calculate a separate price index for persons 62 and older. This index, called the CPI-E, has been extended back to December 1982. While the constructed index is far from perfect, it does provide some sense of whether or not older people face very different rates of inflation. If the adjustment had been based on the CPI-E instead of the CPI-W, the 2021 increase would have been 1.4 percent instead of 1.3 percent – 0.1 percentage point higher.

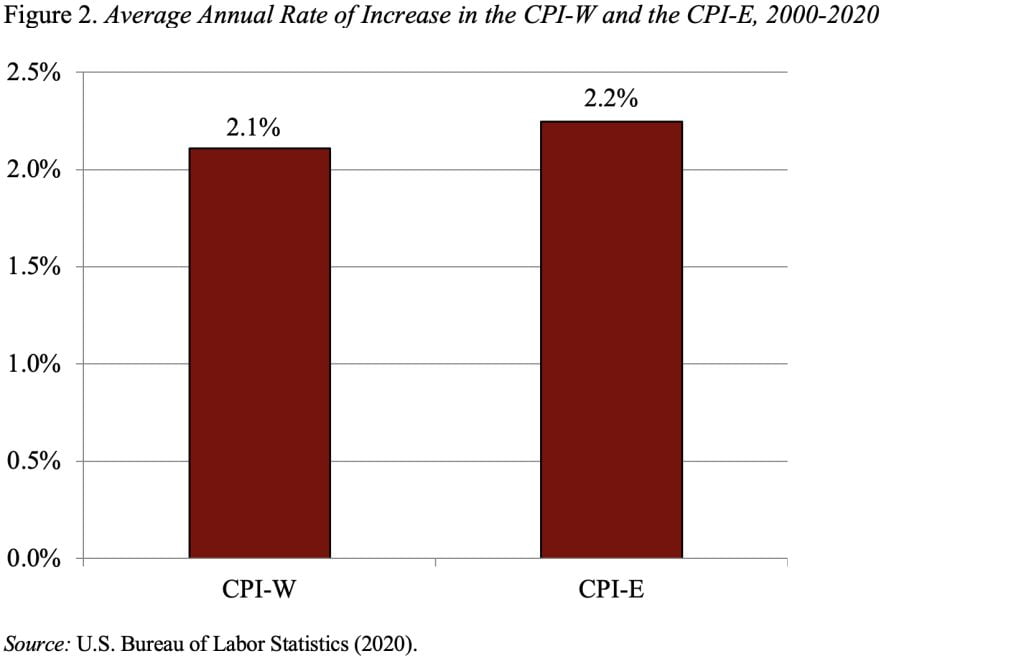

How about over the longer run? In the 1980s and 1990s, the CPI-E regularly increased faster than the CPI-W. That pattern changed, however, after the turn of the century as the rate of increase in the price of medical care slowed. Over the last 20 years, the two indexes have produced almost identical results (see Figure 2).

Assuming the current pattern continues to hold, I don’t think I’d go for a big fight over the price index. On the other hand, if medical care costs start to rise more rapidly again, it may be time to construct and use an index designed specifically for older Americans.