Social Security in the Cross Hairs: Disability Insurance

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

CBO’s assumptions are at odds with SSA, the 2015 Technical Panel, and the facts.

As I have said before, Social Security may be at risk after the November elections. Critics are writing op-eds saying that benefits – relative to previous earnings – are very high, and the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has come out with an astounding estimate of the 75-year deficit. The stage is being set for benefit reductions. Cutting benefits would be a huge mistake, given that half the private sector workforce does not participate in an employer-sponsored plan and that those lucky enough to participate in a 401(k) have combined 401(k)/IRA balances of $111,000 as they approach retirement. Therefore, it is very important to take a hard look at the emerging characterization of the program. This blog focuses on the Disability Insurance (DI) component of the Social Security program because CBO’s assumption about the growth in DI beneficiaries is a significant factor explaining its very high Social Security deficit projection.

The DI program has been the focus of intense interest in the past year because the DI trust fund was scheduled for exhaustion in 2016, which would have required immediate cuts in benefits. Fortunately, the 2015 Bipartisan Budget Act increased the allocation of the Social Security payroll tax dedicated to the DI trust fund from 1.8 percentage points to 2.37 percentage points for the years 2016, 2017, and 2018, extending the solvency of the DI trust fund to 2022.

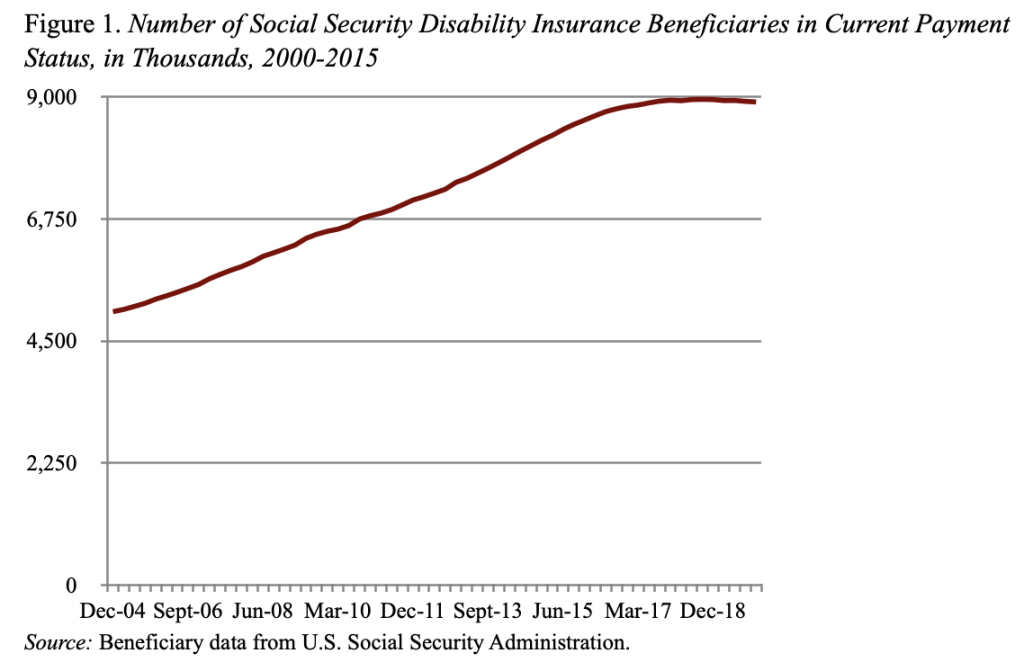

The bigger question is the outlook for the number of DI beneficiaries going forward. After decades of controversy over what was causing the upsurge in claimants, the 2015 Technical Panel, which I chaired, agreed with the Social Security Trustees that the factors that led to the secular rise in SSDI prevalence over the past three decades are not likely to recur. Indeed, in 2015 the DI program notched its first year-over-year decline in the stock of beneficiaries in more than 30 years. This is important news.

Three factors explain the increase over the last 30 years in the percentage of the non-elderly population receiving DI benefits. First, legislation enacted in 1984 broadened the definition of disability and provided applicants and medical providers with greater opportunity to influence the decision process. Second, the baby boomers began aging into their peak disability years in the mid-1990s, and, with the 1984 legislation, the baby boomers aged into higher incidence rates than they would have otherwise. Third, as female labor force participation rose, female insurance and incidence rates caught up to those of males.

At this point, the three drivers of the increased prevalence of disability beneficiaries have played themselves out: women have now nearly caught up with men, the Baby Boom is moving into retirement, and the percentage of DI claims allowed has been declining since 2001, suggesting a regime shift. Indeed, the number of DI beneficiaries in current payment status declined from 8,954,518 in December 2014 to 8,909,430 in December 2015 (see Figure 1). It seems very hard to argue, as CBO does, that the percentage of the non-elderly population receiving DI benefits will increase.