Social Security Is the Most Valuable Program in This Country

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Let’s stop cutting its operating budget.

Headlines on CNN characterized Social Security’s disability process as “broken.” That assessment is heartbreaking, but also the result of purposeful neglect. For those who view government as an intrusion, the strategy has been to frustrate people where they interact with government. And most people interact with the federal government in one of two places – the Internal Revenue Service and the Social Security Administration. Congress has starved both of these agencies. The American people deserve better.

Social Security is amazing. Designed in the 1930s, it still fits the needs of today’s Americans. It is the backbone of our retirement system, currently providing monthly benefits to 49 million retired workers and 3 million spouses and children, as well as 6 million survivors of retired workers. In addition, the program provides disability insurance benefits to 9 million people, including those with disabilities themselves, their spouses, and children.

Dispersing $1.2 trillion annually to 66 million people requires adequate staff and updated technology. But Congress has underinvested in Social Security for more than a decade, and the challenges facing the agency have been exacerbated by COVID.

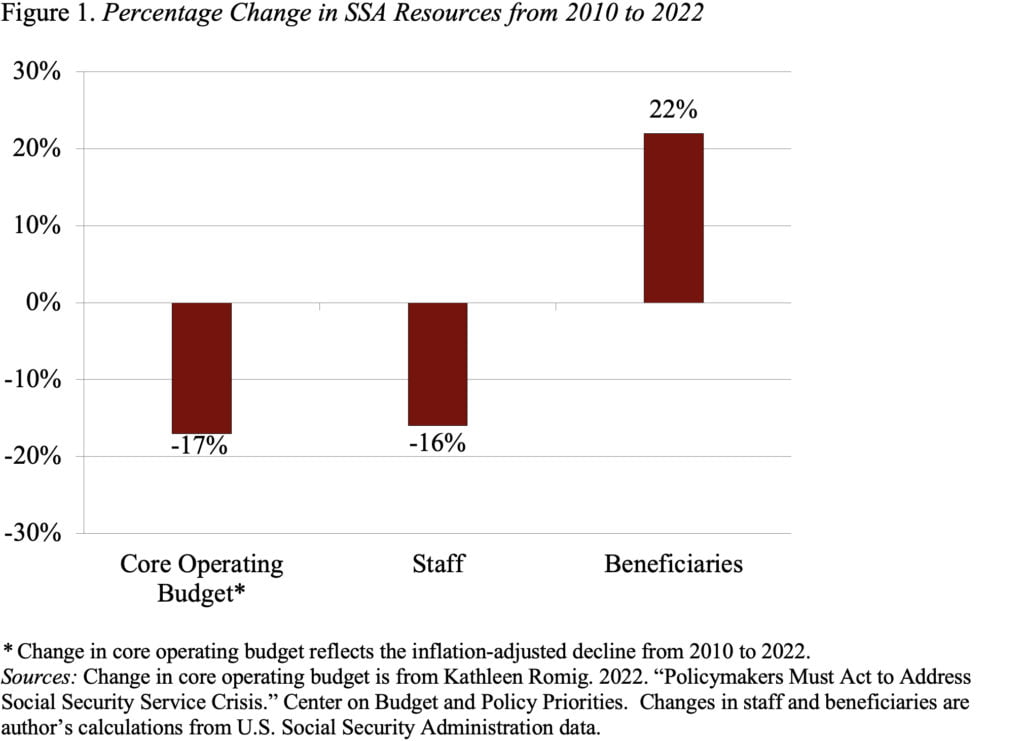

While the money to administer Social Security comes from workers’ contributions to the program – not from general revenues – Congress sets limits on the amount that SSA may spend on its operations each year. Between 2010 and 2022, Congress shrank SSA’s operating budget by 17 percent in inflation-adjusted terms (see Figure 1). These cuts occurred just as baby boomers reached their peak years for claiming retirement and disability benefits. As a result, SSA’s staff is down 16 percent over a period when Social Security beneficiaries have increased by 22 percent (Figure 1).

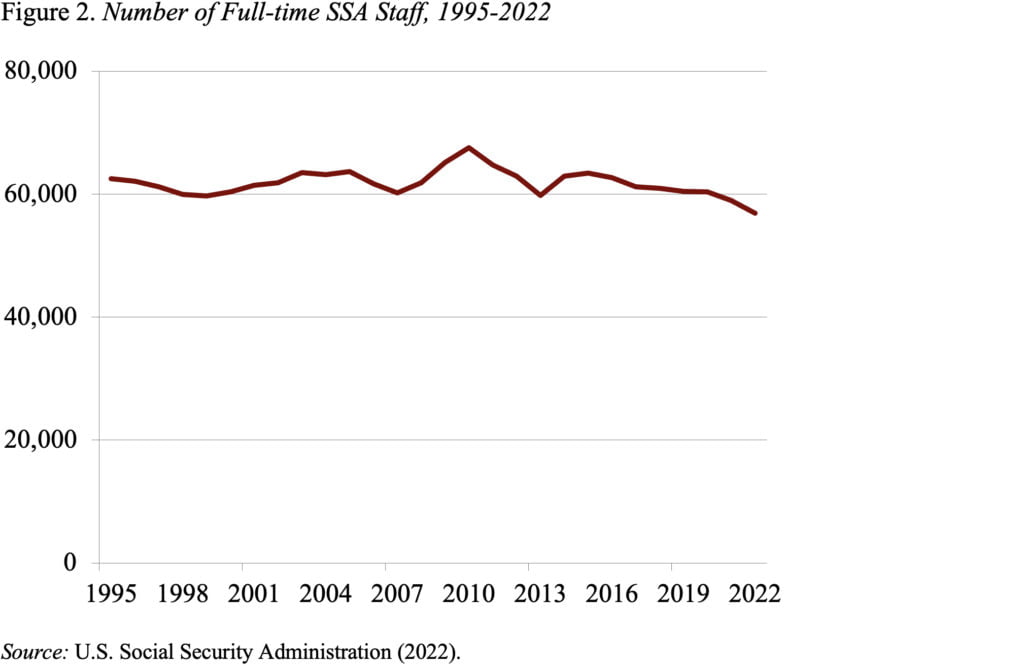

COVID has made things even harder. SSA was forced to close its field offices in March 2020, which only re-opened last spring. And the agency lost about 4,000 employees during the pandemic, reducing staffing to its lowest level in decades (see Figure 2). Increasingly, the agency has to rely on overtime to process a critical workload. The impact of the COVID office closures and a shrinking staff have clearly affected service delivery – since the onset of the pandemic, the average processing time for initial disability claims has increased by two-thirds (from 132 to 220 days).

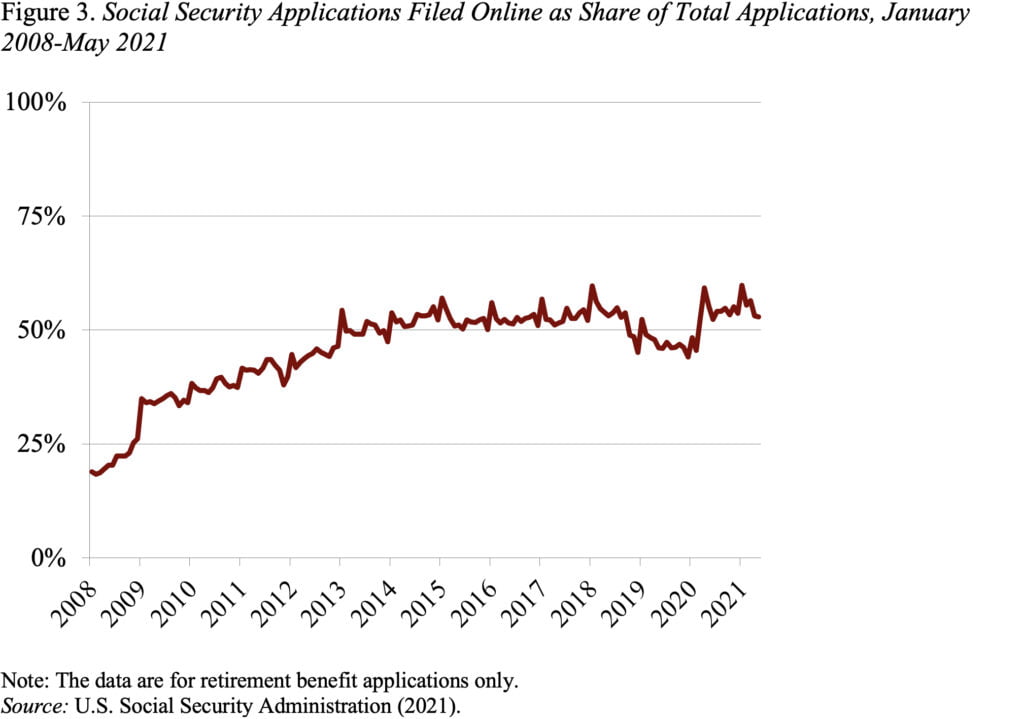

One could argue that, at least on the retirement side, web-based tools could help ease the burden on staff. Indeed, SSA launched its first online claims application for retirement benefits in 2000. Although the monthly online application rate initially grew significantly, it has slowed considerably in the last decade – hovering at around 50 percent since 2013 (see Figure 3). Moreover, a recent study by my colleague JP Aubry concluded that even many of those who claim online contact SSA at some point in the process. So the share of those who claimed entirely online is well below 50 percent. This percentage may increase somewhat in the future as younger cohorts come through with more familiarity with online tools, but a significant share will continue to contact SSA in-person or by phone when claiming benefits.

In short, online options will not solve Social Security’s problem. The agency needs more money for staff and technology to operate effectively. Social Security has the money – our payroll tax contributions – the Congress only needs to let the agency spend it.