Social Security May Be the Most Powerful Equalizing Force in Our Society

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Despite numerous caveats, the Actuaries’ estimates of returns convey the right message.

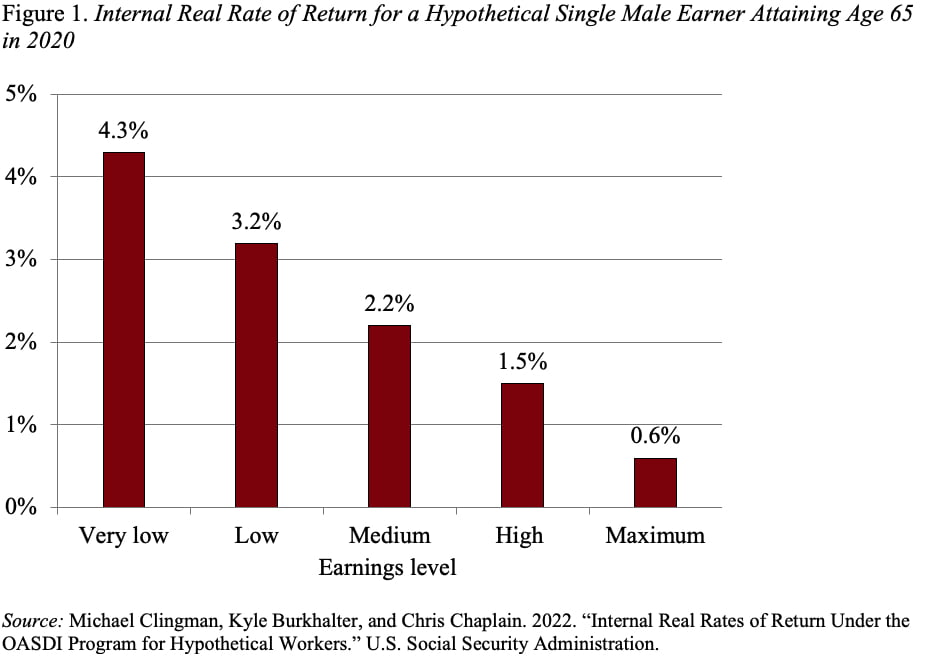

Each year, the Social Security actuaries issue a report on the internal real rate of return that individuals and married couples would have to earn on their payroll tax contributions in order to cover their promised disability and retirement benefits. These numbers, which are based on hypothetical earners, show how returns vary by earnings levels, over time, and by family structure.

My focus here is on the progressivity of the Social Security program – that is, how benefits vary by earnings. Figure 1 shows that internal real rates of return decline as earnings increase; for a single man, very low earners receive benefits equivalent to earning a real rate of 4.3 percent on their contributions; the comparable rate for those who earn the taxable maximum is only 0.6 percent. This pattern is the outcome of a benefit formula that replaces a much higher percentage of low earnings than high earnings.

In some ways, the internal real rates of return understate and in some ways they overstate the progressivity of the Social Security program. Let’s start with the most straightforward issues.

The major factor that makes the program more progressive than the rates of return suggest is that the government taxes Social Security benefits under the personal income tax. Specifically, individuals with more than $25,000 and married couples with more than $32,000 of modified adjusted gross income must pay taxes on up to either 50 percent or 85 percent of their benefits. Thus, the effective internal real rate of return is lower for higher earners than reported above.

On the other hand, the calculations overstate the progressivity of the benefit structure, because they do not reflect any differences in life expectancy by earnings levels. The tendency for higher earners to live longer than lower earners would increase returns at the high end and reduce them at the low end. In addition, recent research has shown that the actuarial adjustment for early claiming is too large; and this particularly hurts lower earners, who are more likely to claim retirement benefits at 62. Similarly, the increase in benefits for later claiming is too large, which helps higher earners, who are more likely to delay claiming to 70.

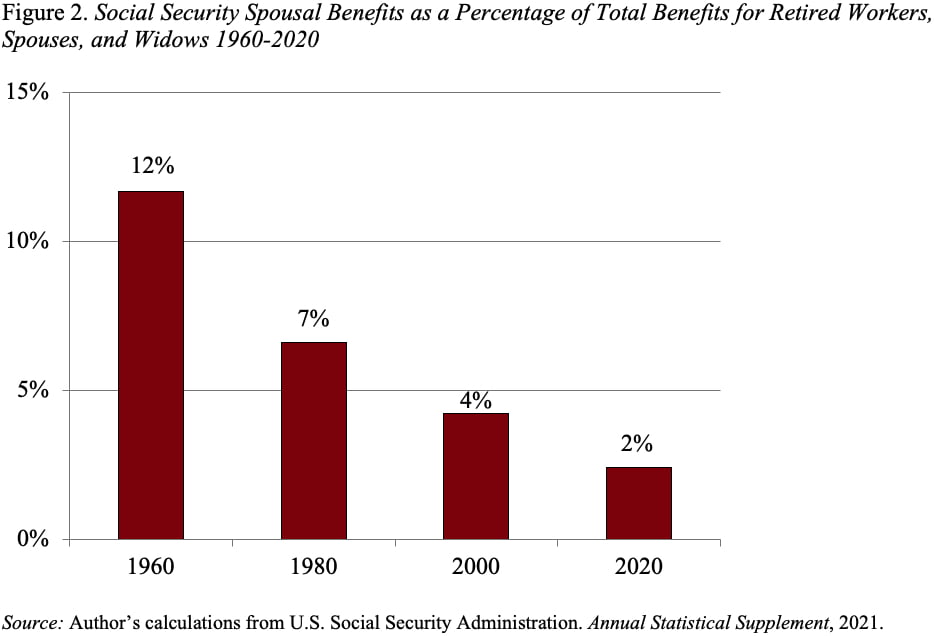

Two slightly more complicated issues are also relevant to assessing the progressivity of the Social Security program. The first pertains to family structure. The old argument was that the progressivity disappears when the unit of observation moves from the individual worker to the couple. The 50-percent spousal benefit was very helpful to single-earner couples, and traditionally these couples tended to be headed by higher earners. My sense is that this issue has largely disappeared as women at all earnings levels have flocked into the labor market and spousal benefits have declined to 2 percent of payments to retired workers and their spouses and widows (see Figure 2).

The final issue is that rates of return describe only a portion of the benefits people receive from Social Security. The program also provides insurance against extreme outcomes, such as ending up as a very low earner, dying or becoming disabled at a young age, or living to very old ages. Intuition would suggest that higher earners with longer life expectancy would gain more from Social Security’s guaranteed lifetime income. Interestingly, recent work suggests that it is the variability in possible outcomes – more than years of expected life – that determines the insurance value of the annuity. As it turns out, Black workers, many of whom are lower earners, face greater variability and therefore gain more in insurance than whites.

So where do all these caveats leave us? For my part, I think that the Actuaries’ calculations paint the right picture. Social Security is a powerful equalizing force in our society.