Social Security: What the Budget Guys Get Wrong

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

The program needs more money, but not because it increases the deficit.

The Concord Coalition, one of a number of federal budget watchdog groups, has been driving me crazy of late. The repeated message is that our deficits are too high, and therefore we have to do something about Social Security and Medicare. They attempt to buttress their arguments by sending along op-eds written by like-minded experts. And they reiterated their position with the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) release of its 2023 Long-Term Budget Outlook.

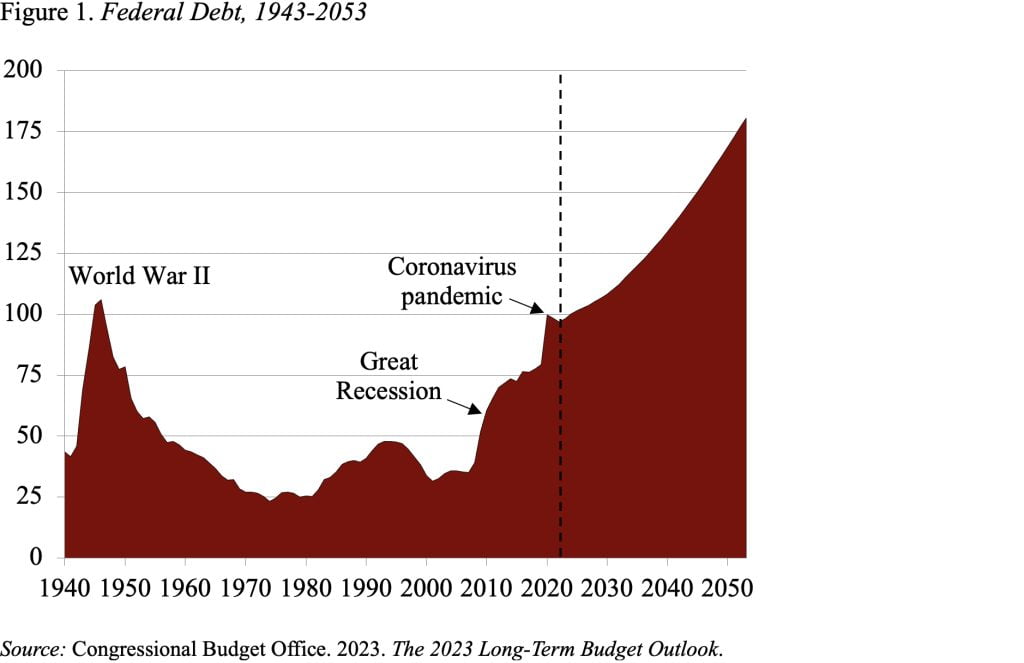

The CBO headlines are indeed alarming. The agency projects that annual federal deficits will increase steadily between now and 2053 (see Figure 1), at which time debt held by the public will reach 181 percent of GDP – an all-time high.

While we clearly need to do something, it is not clear to me why Social Security or Medicare should be on the chopping block. Let’s focus on Social Security.

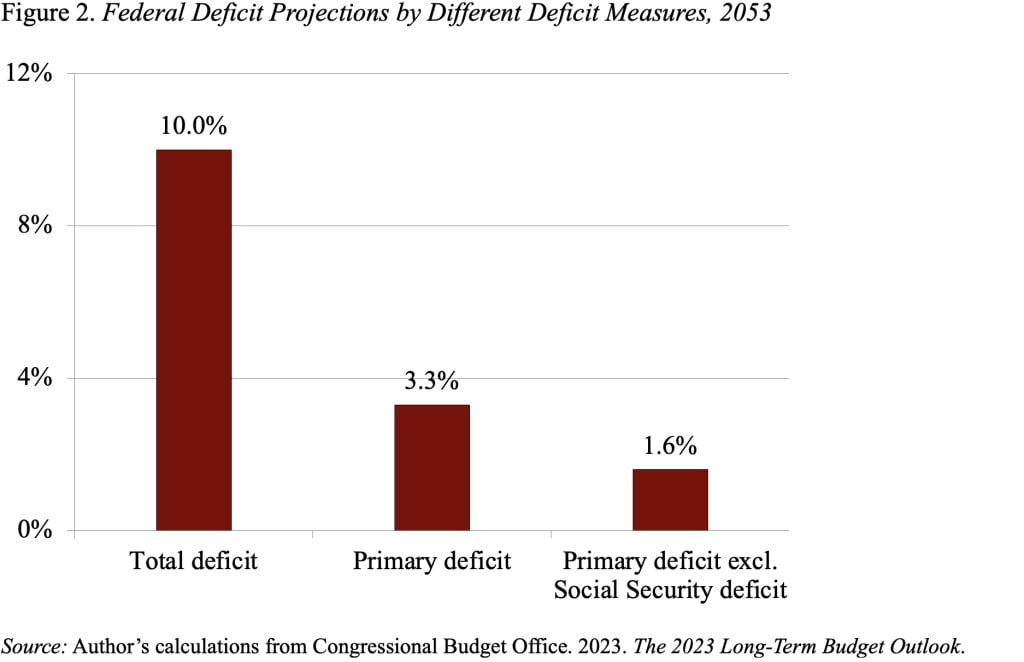

First, Social Security does not contribute one iota to the deficit, since, by law, it can only pay benefits from its trust funds. Once the trust funds go to zero in the early 2030s, Social Security can pay only those benefits covered by incoming revenues – primarily payroll taxes. The CBO projections, however, assume that Social Security continues to pay scheduled benefits even though it does not have the money to do so. Limiting Social Security’s outlays to its authorized levels (about 75 percent of scheduled benefits) cuts the 2053 primary federal deficit (the deficit excluding interest payments) in half (see Figure 2).

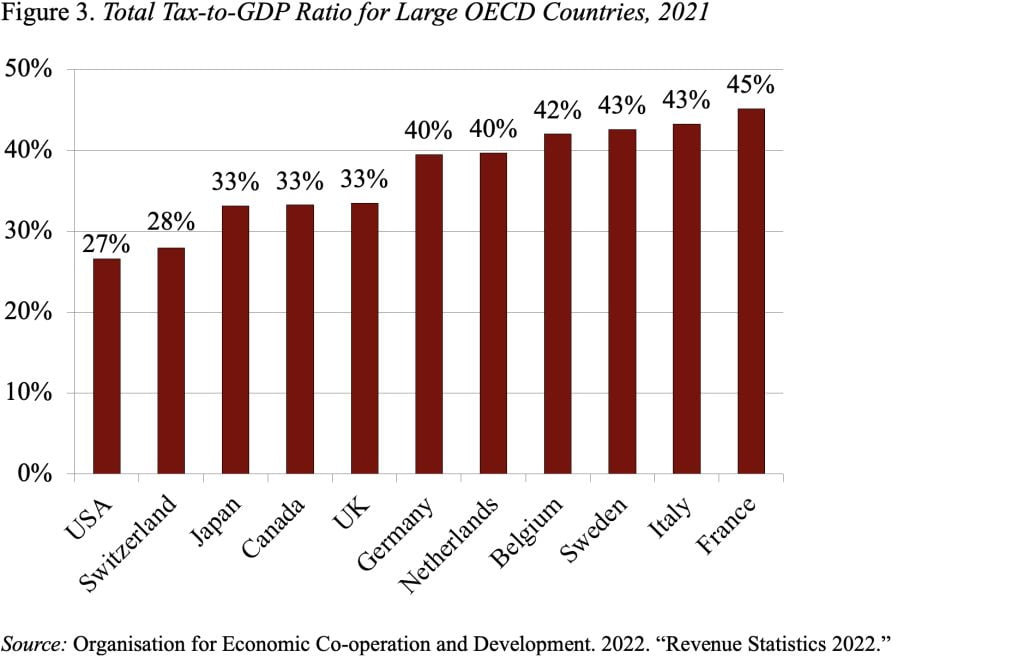

Don’t get me wrong; I want Social Security to continue to pay scheduled benefits. They are the life blood of retirement income for all but the well paid. But paying scheduled benefits requires additional revenues. If the full burden were on the current payroll tax, the rate would have to go up by about 2 percentage points for both the employer and the employee. But a host of other payroll tax options also exist, and, in my view, a strong case can be made for an infusion of general revenues. Americans are dramatically undertaxed compared to other large OECD countries (see Figure 3).

Sorry to keep going on, but the op-ed the Concord Coalition forwarded was also annoying. The authors were two previous congressional staffers who should have known better. But within a few short paragraphs, they put forth three faulty arguments.

- First, they contend that Social Security was instituted when life expectancy was about 65 and now it’s in the high 70s. Since benefits started at 65 and the average person was dead, costs must have been really low indeed! The mistake is looking at life expectancy at birth, which indeed has gone up by 14 years – primarily due to a reduction in infant mortality The relevant numbers are life expectancy at 65, which has gone up 6 years.

- Second, they assert that Social Security will be insolvent in the early 2030s. According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, insolvent is defined as: 1) unable to pay debts as they fall due; or 2) having liabilities in excess of assets. Neither applies to Social Security because it has no liabilities in excess of revenues and therefore can pay all debts as they come due.

- Third, they end their pitch for cutting Social Security with a recommendation to increase the program’s Full Retirement Age, arguing that it’s fair “to tell all 20-year-olds that they should not all expect to retire at 65.” How could they have missed the fact that the Full Retirement Age has moved from 65 to 67?

The bottom line – Social Security does need attention, but for program – not budget – reasons. Future retirees will need the level of protection that Social Security currently provides. There is no manna from heaven. Revenues need to be raised. Fortunately, our taxes relative to GDP are really low compared to other OECD countries, so we are well-positioned to raise the required revenues.