Taxing Inheritances Under the Income Tax is a Great Idea

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

But subjecting inheritances to the payroll tax in addition could be even better

In a great new book, BC Law professor Ray Madoff describes how the federal tax code has created two separate societies – working Americans who earn wages and pay taxes to support government programs and the ultrawealthy who have removed themselves from the tax system almost entirely. The wealthy often avoid earned income, which means they escape payroll taxes entirely and ordinary income rates under the income tax. In addition, they can avoid capital gains taxes by not selling their appreciated assets and instead borrowing to support their life styles. And best of all, they inherit money tax free. To remedy this situation, Madoff suggests: 1) repealing the estate tax, which no longer brings in meaningful revenues; 2) taxing inheritances – in excess of a $1 million exemption – under the income tax; and 3) taxing capital gains not just upon sale, but also when assets are transferred either as a gift or at death.

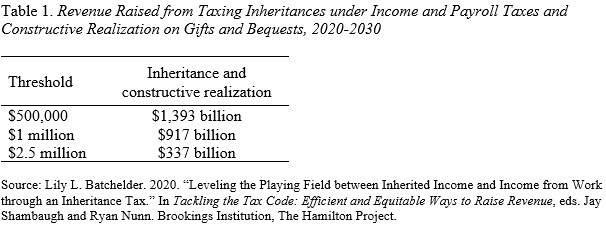

How feasible are these proposals? And how much money would they produce? The proposal to tax gains upon transfer has been around for decades and actually has been enacted in Canada. The proposal to tax inheritances received by heirs – rather than estates left by decedents – has been suggested by a number of other scholars. The most recent incarnation comes from Lily Batchelder of NYU Law School, who served as Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for tax policy from 2021 to 2024. Batchelder’s proposal is more ambitious than Madoff’s – and particularly interesting to anyone interested in Social Security – in that it would tax inheritances under the payroll tax as well as the income tax. Revenue estimates were provided by the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center for three levels of lifetime exemptions: $500,000, $1 million and $2.5 million. For consistency with the Madoff proposal, the following discussion assumes an exemption of $1 million.

The Batchelder proposal has four features. First, any taxpayer who receives gifts and inheritances in excess of $1 million would be required to pay income and payroll taxes on gifts and bequests. Thus, the excess amount would appear in ordinary income on their income tax Form 1040. In addition, the excess inheritance would be subject to Social Security and Medicare taxes (currently 15.3 percent) on their Form 1040. The proposal envisions no Social Security maximum earnings threshold for this new type of taxable income. Revenues collected would go to the Social Security and Medicare trust funds. Taxable inheritances could be spread out over the current year and the previous four years to smooth out income spikes. All exemptions and the amount of prior inheritances would be adjusted for inflation.

The second feature of the proposal would apply constructive realization for income tax purposes to large accrued gains on gifts and bequests, repealing carryover basis and stepped-up basis. The proposal would maintain current law for the first $100,000 in accrued gains ($200,000 per couple) plus $250,000 for personal residences ($500,000 per couple). This part of the proposal would also apply to charitable transfers, with the tax liability paid by the recipient.

The third feature of the proposal would address the politically sensitive issue of family-owned businesses, farms, and primary residences through special provisions, and the fourth would limit tax avoidance through a number of reforms to the rules governing the timing and valuation of transfers through trusts and other devices.

The revenue estimates show that three changes –1) eliminating the estate tax; 2) taxing gifts and inheritances in excess of a $1-million lifetime threshold at ordinary income rates and a 15.3-percent payroll tax rate; and 3) eliminating step up in basis – would raise revenues by $917 billion (see Table 1). The comparable number for a $2.5-million threshold is $337 billion and for a $500,000-threshold is $1,393 billion.

The estimates are rough because of data limitations and reliance on 1992 data for the distribution of estates among heirs. The estimates also likely underestimate the effect of the whole proposal, since they do not include revenues from applying constructive realization to charitable transfers and other revenue-raising proposals. Moreover, prices have increased about 30 percent since 2020, so these estimates would be $1,811, $1,192, and $438 billion in current dollars and would grow with wealth over time. In contrast, revenues from the current estate tax are projected to be $37 billion, and will likely decline as a percentage of wealth going forward.

For anyone interested in Social Security, a proposal that provides additional revenues from the very wealthy requires serious thought. And taxing gains at death may make older Americans less interested in hanging onto their over-sized family homes to save taxes. Even if you don’t agree, it’s nice to think about options to make sure that we are not a two-class society.