The One “Big Beautiful Bill” Provision That Says It All

Geoffrey T. Sanzenbacher is a columnist for MarketWatch and a professor of the practice of economics at Boston College. He is also a research fellow at the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

How the OBBBA Cuts a Tax that Truly Benefits Only the Mega Rich.

Like the majority of Americans, I sometimes find myself unimpressed with the U.S. Congress. In fairness, they have a tough job balancing the interests of a country as large and diverse as the U.S. Yet, the recently passed One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) has left me scratching my head just a bit more than usual.

As I wrote about last month, the OBBBA enforces work requirements that will likely deprive many of Medicaid benefits yet with few employment gains. That’s bad, but such cuts could be forgiven if made in the service of reducing the federal debt. After all, the debt-to-GDP ratio is near an all-time high despite falling slightly during the Biden Administration. But the CBO estimates that the OBBBA will increase the debt by over $3.9 trillion over the next decade. OK, but maybe all those apparently costly tax cuts will benefit mainly middle-income households. Such cuts could offset some of the rising gap between the middle-class and the ultra-wealthy that has developed over the last 45 years. Except that the OBBBA does the exact opposite – the biggest gains go to the top of the income distribution.

I think that one provision of the OBBBA illustrates my basic problem with this bill and says a lot about the priorities of Republicans in Congress. That provision increases the estate tax exemption to $15 million per individual and makes that increase permanent (with adjustments for inflation). Without the OBBBA, the estate tax exemption would have gone down to $5 million next year as a prior increase expired. Under the OBBBA, any amount that an individual leaves behind to heirs above the $15 million exemption will be taxed at the current rate of 40 percent. So, under OBBBA, the heirs to an individual who dies with $20 million left behind as a taxable inheritance would owe $2 million in taxes, or 10 percent of the estate. Under a $5 million exemption, they would have owed $6 million.

So, what’s my problem with increasing the estate tax exemption? After all, many people argue that the estate tax is an unfair form of “double taxation.” Under this interpretation, people are forced to pay taxes on their wealth having already paid for it when that wealth was first earned as income. Others point out that the estate tax hurts family businesses, sometimes even requiring their sale to avoid handing down the business and triggering the tax.

In my opinion, both of these arguments are weak. The estate tax is paid for by heirs not by the deceased who are, you know, dead. Those heirs are decidedly not being double taxed as they didn’t earn the money in the first place. On the small business side, there’s perhaps a bit more merit. But, the typical small business is nowhere near large enough to be affected by an estate tax, even with the smaller $5 million exemption. In my own calculations using the Survey of Consumer Finances, the median self-employed person has a household net worth of about $460,000. One has to look above the 88th percentile to find self-employed people with household net worths above the $5 million exemption. Plus, the individual exemption is doubled for couples to $10 million, moving the number to the 93rd percentilefor affected businesses with a married couple involved, as many are. The OBBBA pushes those numbers to the 96th percentile for an individual and the 99th percentile for a couple. Most small businesses wouldn’t be affected by the estate tax with or without the OBBBA.

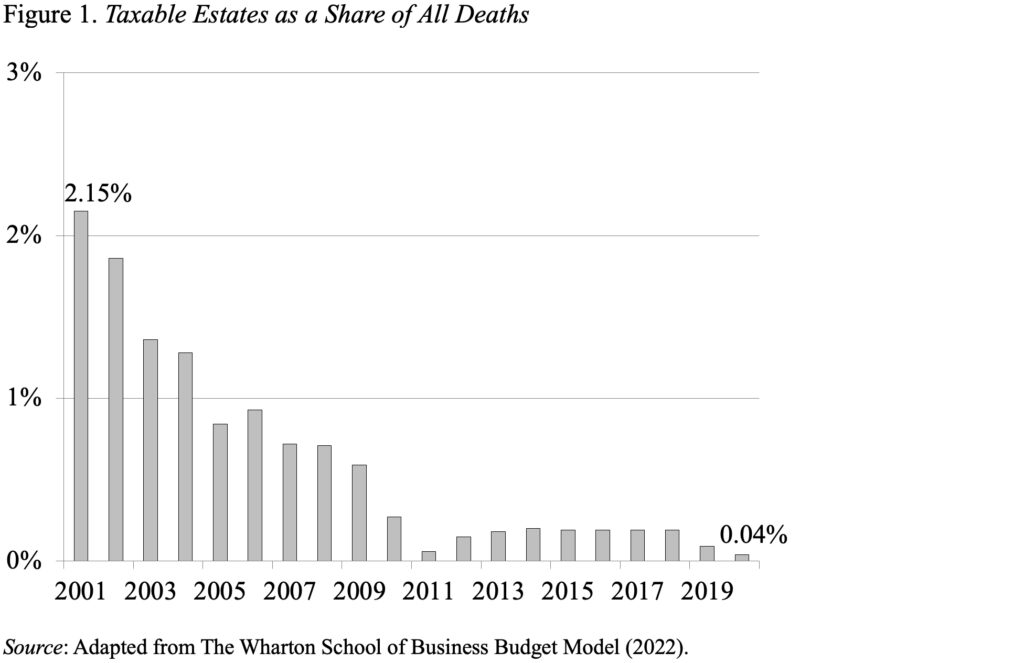

Indeed, the OBBBA is part of a long-term trend of weakening the estate tax so that even most very, very rich people in the U.S. are not affected by the tax at all. Figure 1 – based on an analysis from the Wharton School of Business – illustrates this trend by showing that over the two decades prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the share of families paying any estate tax fell precipitously. It used to be that those in the top 2 percent of the distribution paid – now it’s all the way up to only the top 0.1 percent.

The result has been a corresponding decline in revenue generated from the tax from 0.23 percent of GDP in 2001 to 0.04 percent of GDP in 2020, a reduction of more than 80 percent. Indeed, that same Wharton School of Business analysis found that had the estate tax’s rules stayed constant from 2000-2020, the tax would have generated about $650 billion more in revenue than it did. Perhaps if this revenue were collected from those at the top of the income distribution instead of missing, Republicans in Congress wouldn’t feel compelled to perform such draconian cuts to Medicaid affecting those at the bottom.

It’s funny that part of the argument in enforcing those Medicaid work requirements is to encourage people to pull themselves up by their bootstraps. I guess the same logic doesn’t apply to the children of the very rich, most of whom have probably already had every advantage and under the OBBBA can get yet another one – an untaxed estate.