Theory Suggests that Workers Offset Benefit Cuts with More Saving Elsewhere

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

But evidence from state and local workers suggests that doesn’t always happen.

The economist’s simple lifecycle model predicts that workers will respond to a one-dollar decrease in their defined benefit savings by increasing their supplemental savings by one dollar. Whether this prediction holds in practice may turn out to be very important for state and local workers. Although the common story is that these workers spend a full career in government and retire with substantial defined benefit pensions, that often is not the case – all plans are not equally generous, many plans may lack the funding to pay full benefits, and one in four public sector workers is not covered by Social Security.

In other words, a lot of reasons exist for state and local workers to augment their pensions with outside saving, and all state workers and most local workers have access to supplemental defined contribution plans – namely 457s, 401(k)s, 401(a)s, and 403(b)s.

To see whether public workers take advantage of these options, my colleagues estimated the relationship between participation in a supplemental defined contribution plan, on the one hand, and low wealth accumulation in a defined benefit plan, low plan funded levels, or lack of Social Security coverage, on the other. To do this analysis, they merged individual-level data in the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) with plan-level data from the Public Plans Database (PPD).

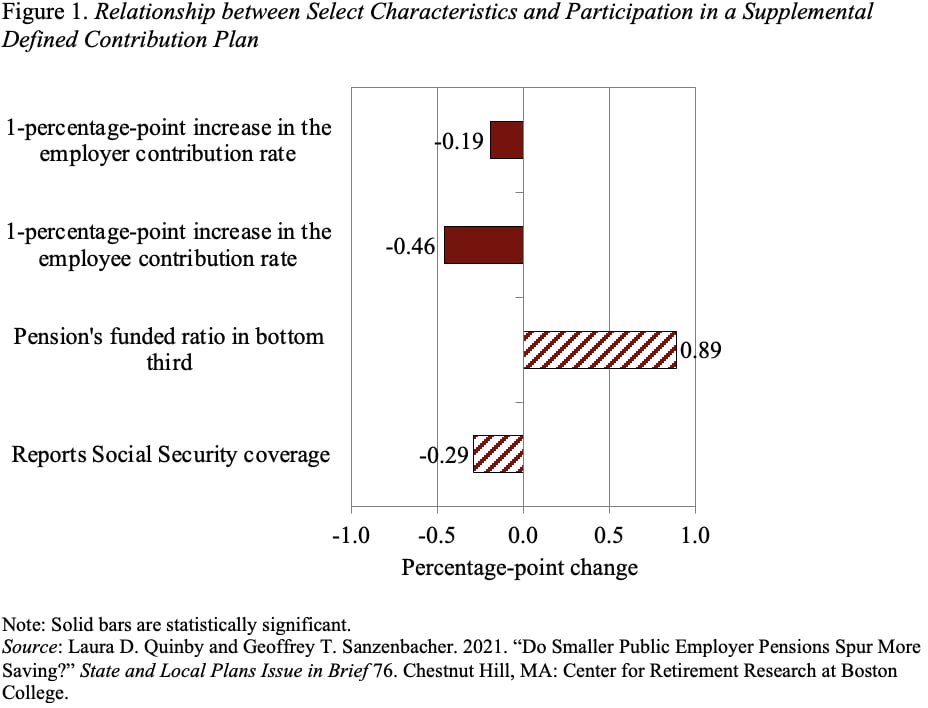

The key results suggest that workers do respond to low contributions to their primary defined benefit plan – the solid red bars in Figure 1 – but the magnitudes are tiny. For example, a one-percentage-point increase in the employer contribution rate is only associated with a 0.19-percentage-point decrease in the participation rate, relative to a baseline of 21 percent. And the striped bars in Figure 1 show that workers do not respond at all to having a very poorly funded pension plan or not having Social Security coverage.

The bottom line is that people do not always respond as theory would suggest. State and local workers may simply not be aware of how much saving is taking place through their defined benefit pension; they may not appreciate the extent to which their plan is adequately funded; and they may not understand the implications of not being covered by Social Security. Whatever the reason for the lack of response, states and localities cannot count on their workers making up for reduced pension income through supplemental savings.