Three Factors that Undermine Social Security’s COLA

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

After a hiatus of two years, it looks as if the Social Security Administration will increase benefits payable in December 2011 by about 3 percent beginning January 1, 2012. This cost-of-living-adjustment (COLA) is an important reminder that keeping pace with inflation is one of the attributes that makes Social Security benefits such a unique source of income. (The other is that the payments continue for life.)

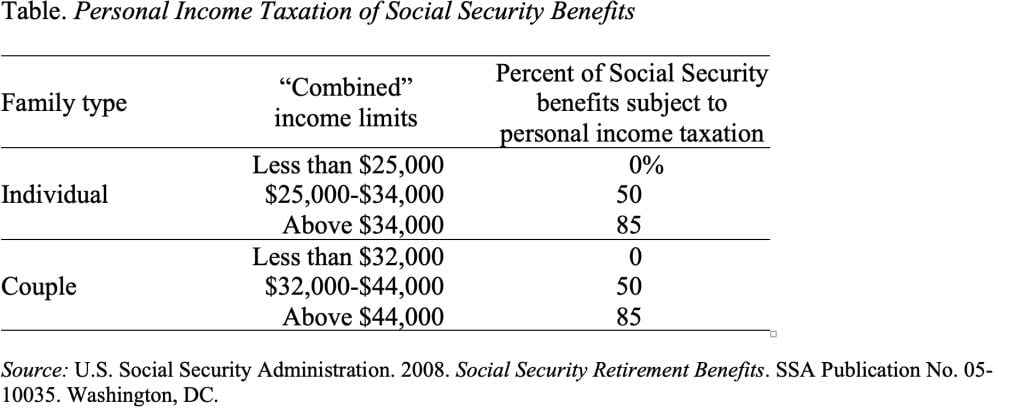

Higher inflation raises three issues, however, about the COLA. The first issue pertains to whether the index used is appropriate for an elderly population. The second relates to Medicare Part B and Part D premiums, which are deducted automatically from Social Security benefits. To the extent that premium costs rise faster than the COLA, the net benefit will not keep pace with inflation. The third issue pertains to taxation under the personal income tax. Because the thresholds for taxation ($25,000 for single taxpayers and $32,000 for joint returns) are not adjusted for wage growth or even for inflation, rising benefit levels mean that taxation reaches further and further down the income distribution.

First, the index. Social Security bases its adjustment on the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W), which does not necessarily reflect the spending patterns of older Americans. In 1987, Congress directed the Bureau of Labor Statistics to calculate a separate price index for persons 62 and older. This index, called the CPI-E, has increased 0.3 percentage points faster than the CPI-W over the period 1982-2011. The CPI-E rose faster because older people devote a much larger share of their budgets to medical care, where prices have increased rapidly. The CPI-E is not a perfect index (it simply re-weights price changes for the whole population to reflect the spending patterns of older Americans), but it does suggest that the current COLA may not fully reflect the inflation experienced by older people.

Medicare premiums for Part B (physician and outpatient services) and Part D (prescription drugs) are deducted from Social Security benefits before they are sent to the recipient. Over the last 30 years, the Medicare Part B premium has increased by about 9 percent annually and the COLA has been about 3 percent. To see the impact, assume the average benefit is about $1,000 per month and the Medicare Part B premium is $100, so the beneficiary receives a net benefit of $900 to spend on non-health items, such as food, shelter, and clothing. The next year, Social Security benefits will increase by 3 percent to $1030 and the Medicare premium to $109, leaving a net benefit of $921, 2.3 percent more than the original $900. Thus, the increase in the Medicare premium offsets some of the cost-of-living adjustment on the net benefit.

The final way that inflation affects Social Security benefits is the extent to which they are taxed under the federal personal income tax. Under current law, individuals with less than $25,000 and married couples filing jointly with less than $32,000 of “combined income” do not have to pay taxes on their Social Security benefits (see Table). Above those thresholds, recipients must pay taxes on up to 85 percent of their benefits. Today, about one third of people who receive Social Security have to pay taxes on their benefits. But the thresholds are not indexed for growth in average wages or even for inflation, so in the future a significantly higher percentage of recipients will be subject to tax.

In short, even Social Security does not fully insulate older households from the erosive impact of inflation, and this is a serious concern given that most other sources of retirement income offer virtually no inflation protection.