To Fix Social Security, Increasing the Wage Base Should Be Part of the Solution

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

I would argue for moderation.

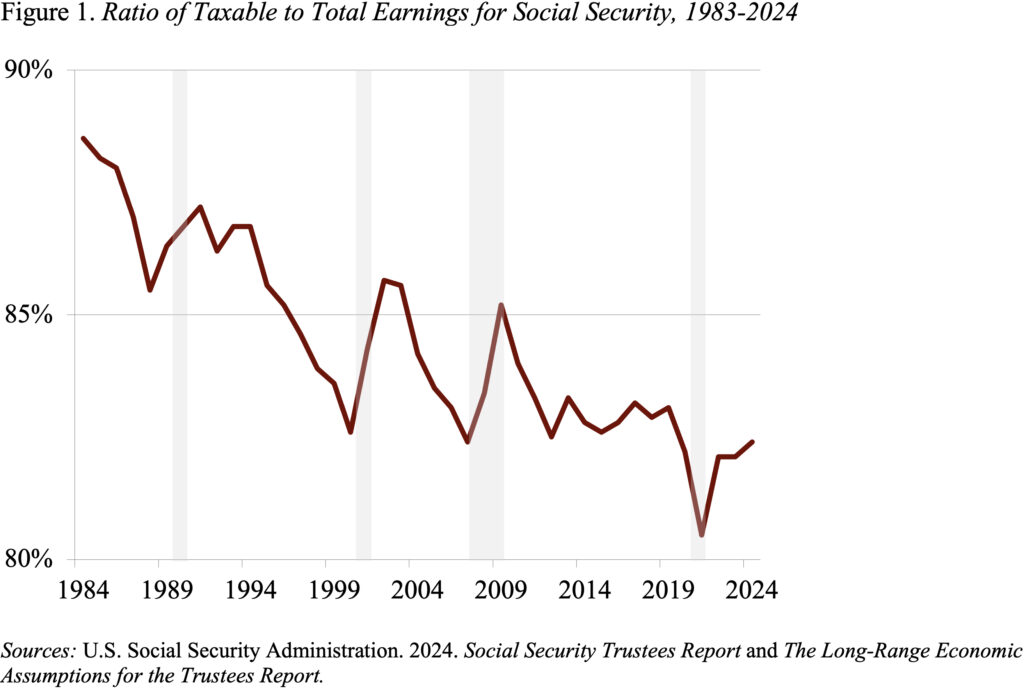

I usually have a strong opinion on issues in my sphere, but have been going back and forth about one component likely to be in any package to fix Social Security – namely, increasing the taxable wage base. Some increase in the wage base is almost inevitable because growing wage inequality has caused the share of wages subject to taxation to decline sharply since the last major piece of legislation in 1983 (see Figure 1).

The minimalist option is simply to raise the taxable limit from $168,600 in 2024 to an amount that would ensure that 90 percent of wages were subject to the payroll tax – roughly $300,000. The most aggressive option would be to take the limit off altogether and offer no additional benefits. In between are options that remove the limit and offer benefits of various generosity.

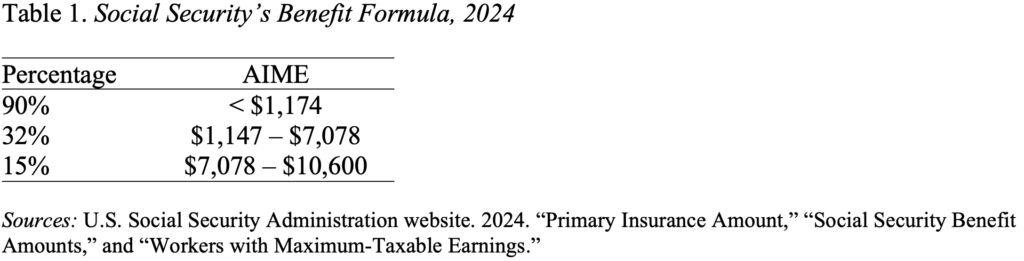

As background, it is helpful to understand how benefits are currently calculated. The first step is to calculate the worker’s average indexed monthly earnings (AIME), which involves adjusting the worker’s wage history for increases in the general wage level, selecting the highest 35 years, and taking the monthly average. The second step is to apply the benefit formula (see Table 1) to calculate the worker’s primary insurance amount. (The percentages in the benefit formula are fixed by law, but the dollar ‘bend points’ are adjusted each year for changes in the national average wage index.) Finally, the primary insurance amount is adjusted actuarially for early or late claiming.

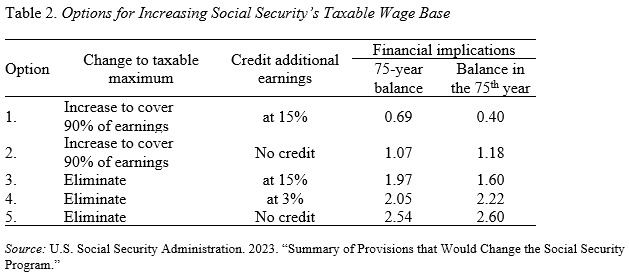

The Social Security actuaries put out a wonderful booklet that contains more than 150 options for closing the 75-year deficit by either cutting benefits or raising additional revenue. Table 2 summarizes 5 of the 19 options for increasing the taxable wage base. For context, the 2024 Trustees Report projected Social Security’s shortfall over the next 75 years to be 3.50 percent of taxable payrolls.

Clearly, the biggest financial gain comes from eliminating the taxable maximum – Options, 3,4 and 5. I don’t like Option 5 because it dissolves any link between payroll tax contributions and benefits, which in the long run could undermine support for the program. Option 3 seems too generous to high earners, and the gains to Social Security would decline over time as persistent wage inequality leads to rapid growth in benefits among the high earners. Therefore, the choice to me comes down to raising the cap to cover 90 percent of earnings or eliminating the cap and adding a 3-percent bracket to the benefit formula (Option 4).

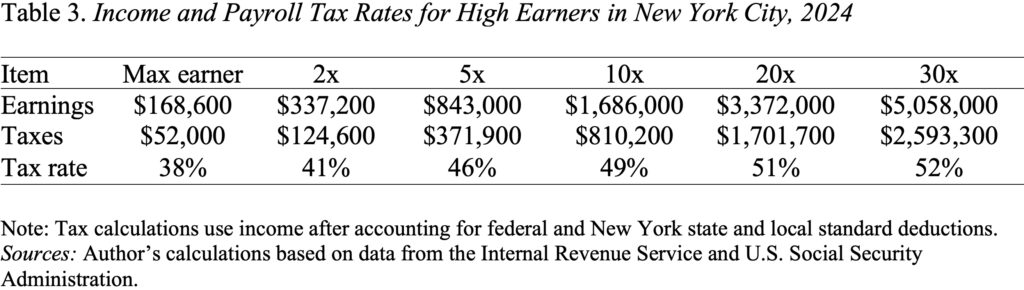

The choice then comes down to how much more do we want to tax high earners. My colleague Ray Madoff at the Boston College Law School makes a convincing case that high earners – that is, people who get all their income in the form of wages and salaries – pay their full share of taxes. Indeed, a quick calculation for those living in New York City suggests that really high earners pay more than half their compensation in income (federal, state, and city) and payroll taxes (no taxable maximum on the Medicare tax plus a 0.9-percent tax on earnings above $200,000 for singles and $250,000 for married couples) (see Table 3). I know New York is on the high side in terms of taxes, but that’s where I get most of my complaints from!

In the end, some combination of Options 1 and 2 seems like the way to go – raise the taxable wage base to cover 90 percent of earnings and credit a small percentage (perhaps 3 percent) of the earnings towards benefits. The big decision for me was not taking the cap off altogether. Thanks for helping me work through my dilemma.