What Role Does State Government Play in Funding Teacher Pensions?

The brief’s key findings are:

- Teacher pension costs have doubled as a share of payroll since 2001, raising concerns about managing this burden amid other education spending needs.

- While school districts rely heavily on state support, relatively little is known about state funding for teacher pensions specifically.

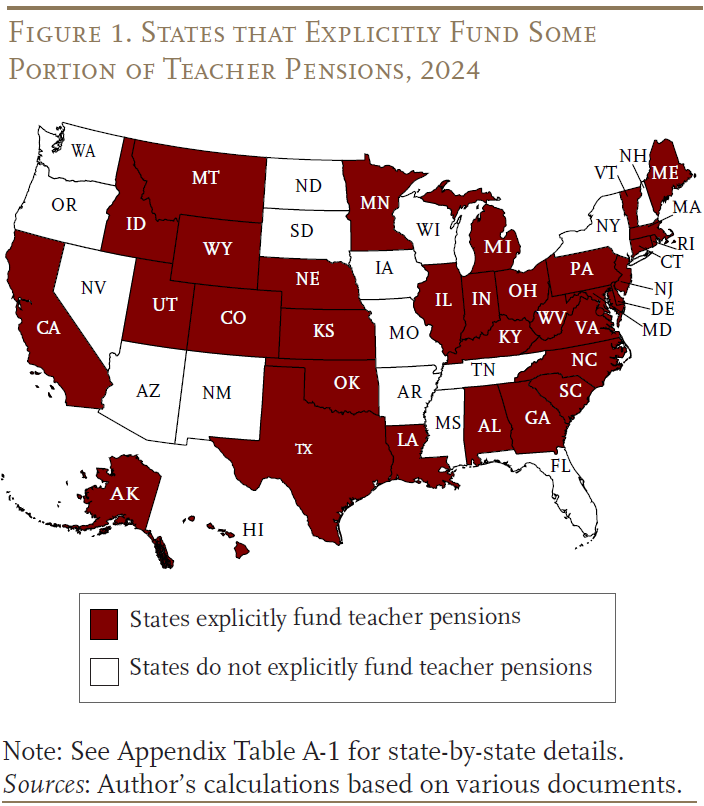

- Strikingly, about two-thirds of states explicitly provide funds for teacher pensions, with 15 of these states paying the full cost on behalf of schools.

- The remaining third of states implicitly help with pensions through basic state aid to schools, but this aid seems to have fallen somewhat behind rising costs.

Introduction

Many who are familiar with state and local government finances are concerned that rising pension contributions could be crowding out important government services.1For example, Nation (2017) finds that rising expenditures on pension benefits in California crowd out spending on higher education and social services. Others, like Eide (2015), believe payments towards pension costs are crowding out spending on core services such as police and fire. And, some academic literature does find that higher pension contributions are associated with reduced employment in local governments and school districts.2Anzia (2019) shows that, in response to a greater share of general revenue spent on rising pension costs, local governments reduce employment instead of raising revenue. The crowd-out of pensions on public services is more prevalent among local governments with collective bargaining. Schuster (2018) argues that public employment in Illinois fell in recent years due to growing pension costs. However, teacher hiring decisions may be different from those in local governments due to legal constraints such as class size mandates and the lack of ability for school districts to raise local revenue. Kim, Koedel, and Xiang (2021) find that higher teacher pension costs relate to lower salary expenditures through workforce reductions rather than salary cuts, but the coefficient is much smaller than Anzia (2019) and Schuster (2018). The issue is particularly acute for school districts, which must maintain a relatively large workforce compared to other government units.

Importantly, school districts are different from other local government entities in that a significant portion of their costs are covered by transfers from state government. So, as the employer portion of teacher pension costs has risen from about 8 percent of payrolls in 2001 to almost 20 percent today, discussions about the role of states in funding teachers’ pensions have grown more frequent. To help inform the discourse, this short primer investigates how, and how much, states contribute to teacher pensions.

This primer has four sections. The first section focuses on states that provide explicit support for some portion of teacher retirement benefits – describing the various types of arrangements, as well as the size and scope of the funding. The second section focuses on the remaining states – here, the school districts are expected to pay for virtually all of teacher retirement costs, but the states implicitly support some portion of these costs through general state-aid programs. The third section documents significant changes made by states since 2001. The final section concludes that about two-thirds of states explicitly support some portion of teacher pension costs, with 15 of these states paying the full cost of teacher pensions. The remaining third of states implicitly help with pensions through the state-aid process, but this support seems to have fallen somewhat behind actual costs.

Which States Explicitly Fund Teacher Pensions?

Very few studies have explored the role of states in funding teacher retirement costs.3A review of the existing literature revealed a one-time survey in 2011 by Ron Snell at the National Conference of State Legislatures, a one-time member survey of retirement system administrators in 2015 by the National Association of State Retirement Administrators, and an academic study of Governmental Accounting Standards Board reporting requirements on states’ special funding arrangements in 2019 (see Costrell, Hitt, and Shuls 2019). Additionally, Randazzo, Dowell, and Golos (2021) focus on Connecticut, while Randazzo et. al (2023) investigate California. And, unfortunately, each of these studies presents a somewhat different sample of states that explicitly fund teacher pensions and excludes some key details on each state’s funding arrangement. So, to better understand the situation, the CRR reviewed the existing studies, pored over current state statutes on pension funding and school finance, and read the financial reports of all the state and local retirement systems that provide retirement benefits to teachers. Below is a summary of the findings.

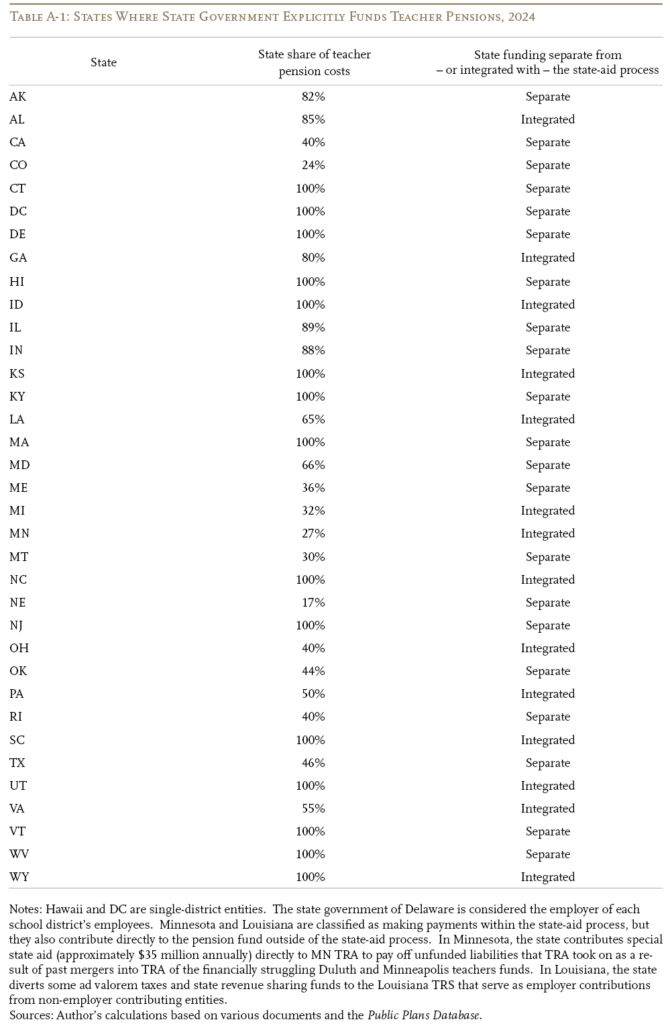

As of June 2024, 35 states (including DC) explicitly provide funds for some portion of the retirement benefits promised to school district teachers (see Figure 1). While most states cover teachers through a state-run plan, a few also have locally run plans for teachers. Overall, then, states explicitly provide some degree of regular funding for 39 separate teacher pension plans.4The following local teacher plans are included in the analysis: Denver Schools (CO), Chicago Teachers (IL), Omaha Teachers (NE), Minneapolis Teachers (MN), St. Paul Teachers (MN), Duluth Teachers (MN), Montgomery County Teachers (MD), Kansas City Teachers (MO), St. Louis Teachers (MO), New York City Teachers (NY), and Fairfax County Schools (VA). In many cases, the state government ends up explicitly providing some degree of regular funding for a local teacher plan because the local plan is merged into the state-run plan (e.g., Denver Schools merged into Colorado PERA, Duluth Teachers and Minneapolis Teachers merged into Minnesota TRA).

To better understand the nuances of each state’s funding arrangement and how it might impact in-state discourse on teacher pension costs, it is helpful to look at two aspects of each state’s policy. The first is the amount of funding that the state provides for teacher pension costs – that is, whether a state funds all the costs or rather contributes a specific portion, such as the payments to amortize the unfunded liability. The second aspect is the pathway through which the state provides the funds – that is, whether it is totally separate from the state-aid process or somewhat integrated.

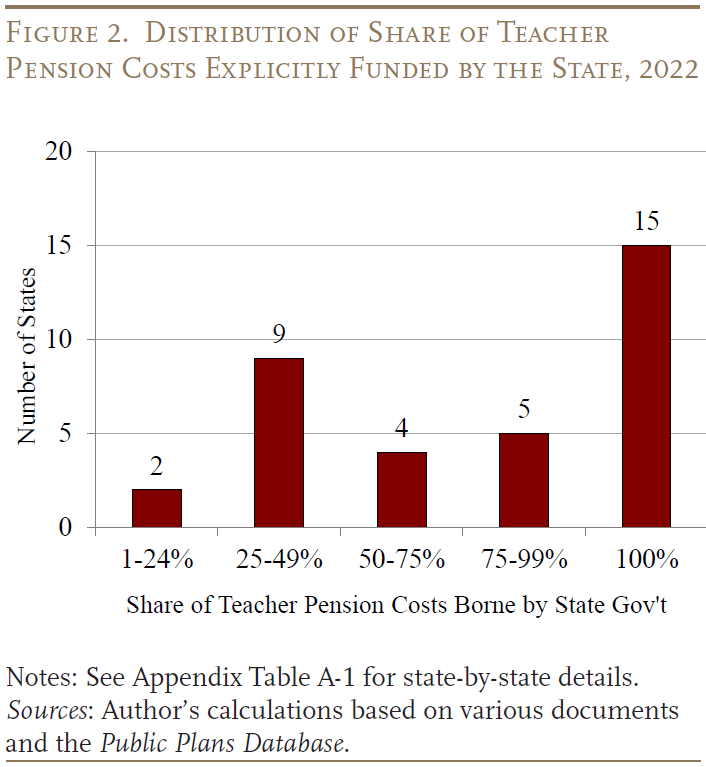

Currently, 15 states (15 plans) explicitly fund virtually all teacher pension costs; and 20 states (24 plans) provide funds for a portion of costs. Using the details from documents describing the funding arrangements for each state and data from the Public Plans Database, Figure 2 shows that – among the states providing funds for a portion of the costs – 11 of 20 pay less than half.

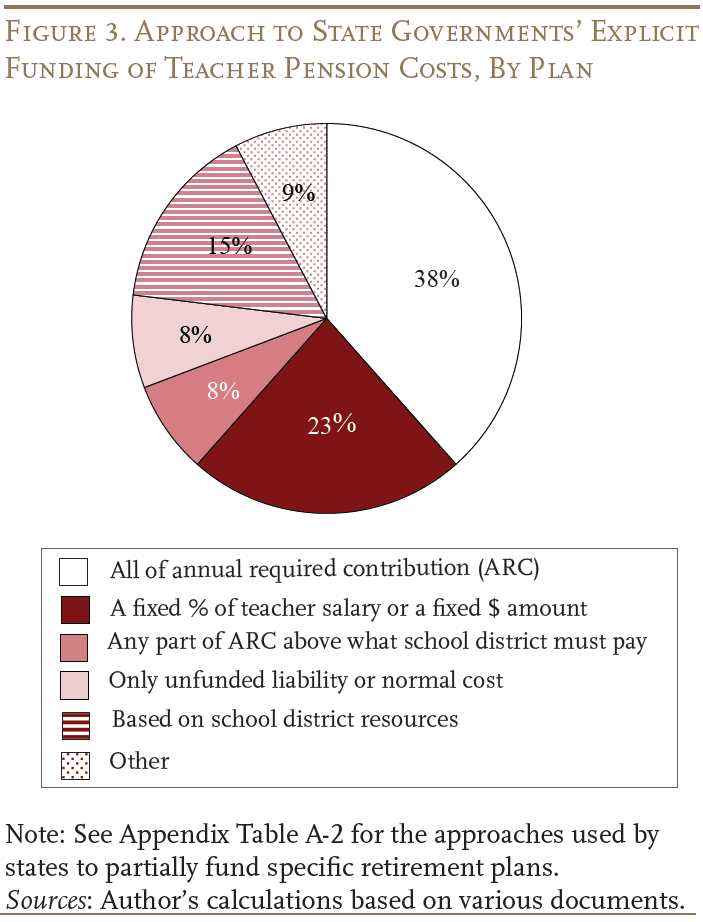

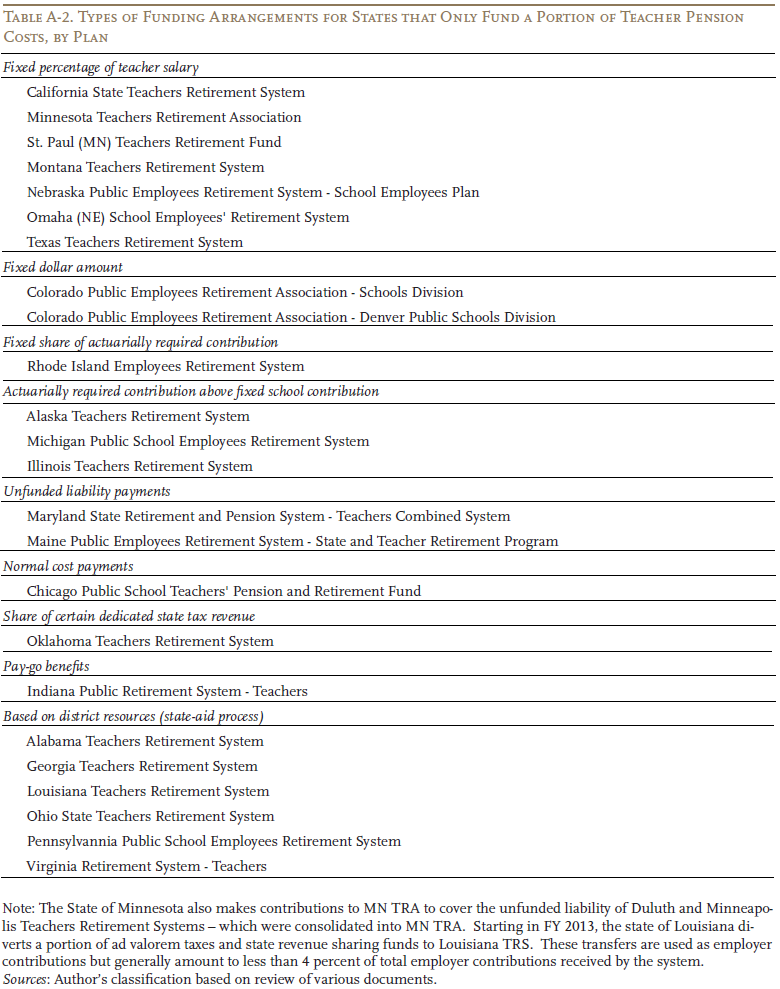

States use various approaches to determine their payments. The most common approach – covering 38 percent of teacher pension plans – is for states to pay all of the annual required contribution (ARC) (see Figure 3). In cases where the state does not pay the full ARC, the most frequent policy – covering 23 percent of plans – is to pay a fixed percentage of salary or a fixed dollar amount.

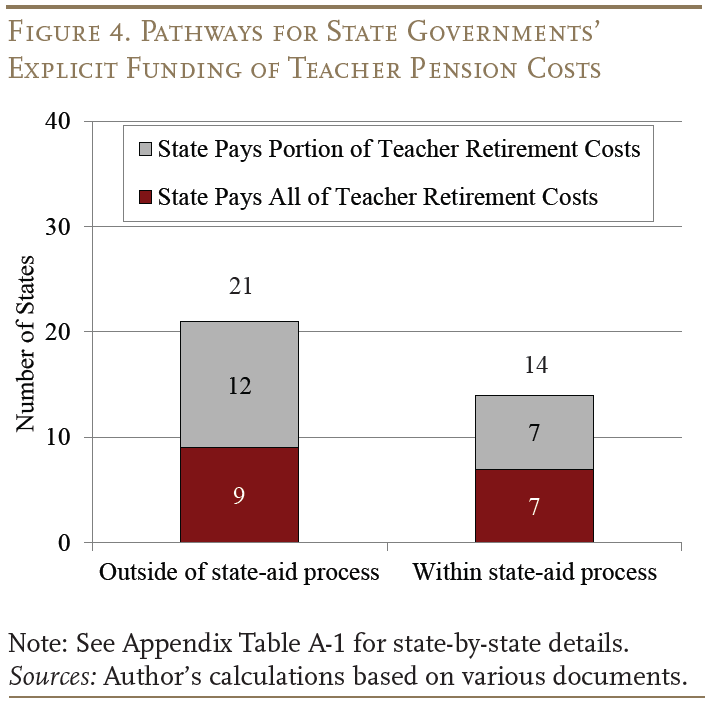

Finally, Figure 4 shows that 21 of the states that explicitly fund teacher retirement benefits choose to transfer money directly to the pension fund, fully separate from the state aid process, while 14 states integrate their funding of teacher pensions with the state-aid process. The approach taken here may matter because of its potential influence on school district decision-making. If states send money directly to the pension fund, it bypasses the school district, making the funding less visible to key stakeholders at the school-district level. If states instead integrate funding for pensions through the state-aid process, then school district decision-makers may be more conscious of pension costs.5While state education aid and state special funding arrangements for teacher pensions are often treated as separate legislative and budgetary processes within state and local governments, all money is fungible, and significant state-level pension contributions on behalf of school districts could reduce state resources available for other school district assistance.

States Implicitly Helping Through General State Aid

Importantly, even the school districts in the states without explicit funding implicitly receive help with their pension costs through the provision of general state education aid. At a high level, state aid provided to school districts is a function of two components. The first component is the state’s estimate of the total cost to provide students adequate basic education – often referred to as the “foundation amount.”6As of 2021, the Education Commission of the States finds that 34 states (including DC) determine costs on a per-student basis, 10 use a per-teacher basis, 6 use a hybrid of per student and teacher, and 1 relies on a guaranteed tax. The second component is the state’s estimate of each school district’s capacity to pay for basic education from its own fiscal resources.7This estimate is generally determined by the property values and income earned within each school district. In general, state aid to school districts is meant to help districts that cannot support the costs of adequate basic education through their own resources. The key question for this primer is to what extent states’ estimates for the cost of basic education incorporate the rise in pension costs over the past two decades.

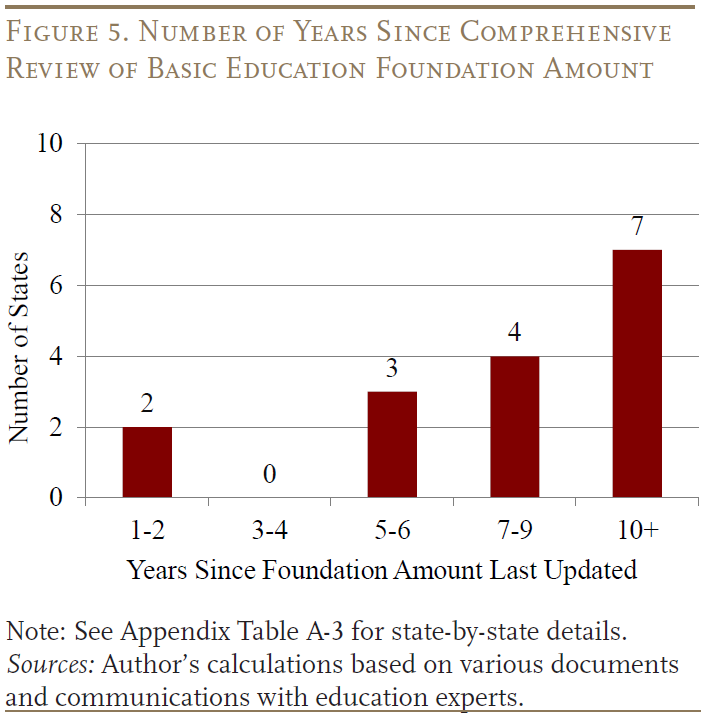

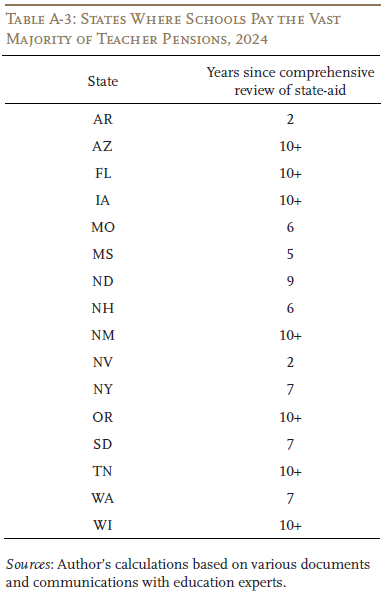

To better understand states’ processes for determining the cost of basic education and how that might impact school districts during periods of rising pension costs, the CRR reviewed policy briefs by education finance experts, academic papers, and state legislation on education funding.8While descriptive state-by-state summaries of state-aid programs are plentiful, they generally focus on the ways that aid is allocated across school districts. They rarely include any meaningful details on the way that estimates of the basic cost of education are derived and subsequently updated – let alone how pension costs are treated within that process. The analysis revealed two important facts. The first is that the cost of basic education in many states is intended – in concept – to include school district pension costs. The second is that states’ estimated costs of basic education are only intermittently updated to account for actual changes in school district costs. Instead, carefully derived estimates of basic education costs are generally increased by inflation for several years until it is determined that another comprehensive assessment is needed.9Griffith (2012) cites Arkansas, Maryland, and Wyoming as being among the few states that determine their foundation amounts through periodic studies conducted by third-party expert organizations. In many cases, early estimates of basic cost were based on existing school district expenditures and simply rolled forward afterward. Indeed, as of June 2024, 7 of the 16 states where schools are responsible for the lion’s share of teacher pension costs had not comprehensively reassessed the adequacy of their state aid for over 10 years (see Figure 5).

For school districts responsible for a large portion of teacher pension costs, the impact of a significantly delayed adjustment can be meaningful. For example, teacher pension costs have risen from about 8 to 20 percent of payroll from 2001 to 2024. If state aid was designed to support roughly 50 percent of average school district costs (including pension contributions) in 2001, a standard inflation adjustment of 3 percent would have resulted in basic education costs that cover only about 40 percent of school district pension costs in 2024.10Assuming no payroll growth, contributions grew 2.5 times from 2001 to 2024 (20/8 =2.5). Simply applying an annual 3-percent inflation increase would grow basic education costs by about 2 times over the same period [1.03^23=1.97]. So, if basic education costs supported 50 percent of pension costs in 2001, they would only support 40 percent of pension costs in 2024 [.5*1.97/2.5=.39].

How Has Policy Changed Over Time?

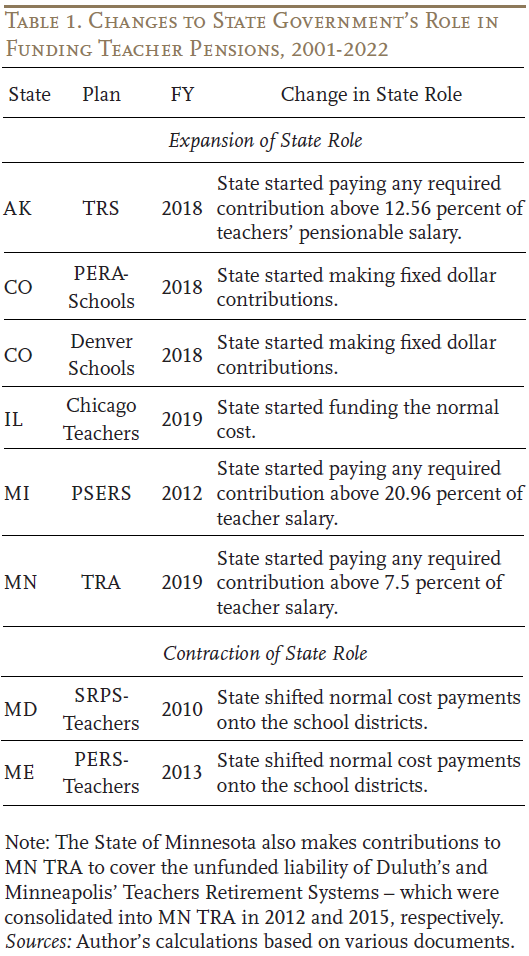

In most cases, the state’s role in funding teacher pensions has changed relatively little since pension costs were at their lowest point in the past two decades. That said, a few notable shifts have occurred. Table 1 details the meaningful changes made in seven states since 2001. Five of the states shifted from no state involvement to some form of explicit state funding. But, interestingly, two states reduced the state’s role by shifting a meaningful portion of costs onto school districts.

Conclusion

School districts are different from other local government entities in that a significant portion of their overall expenditures are related to personnel costs; and they rely heavily on state government transfers for revenue. So, as teacher pension costs have risen from about 8 percent of payrolls in 2001 to almost 20 percent today, discussions over how to manage these costs – and the potential role of state government – have grown more urgent. To help inform the discourse, this short primer investigated the current role of states in the funding of teacher retirement benefits. It found 35 states currently provide some explicit support for teacher pensions, with 5 states beginning to do so relatively recently. Importantly, only 15 of these states pay for all the teacher pension costs on behalf of school districts. And, in the cases where state governments do not provide explicit support for teacher retirement benefits, it seems like the education state aid process has fallen somewhat behind the rise in pension costs.

References

Anzia, Sarah F. 2019. “Pensions in the Trenches: How Pension Spending is Affecting US Local Government.” Urban Affairs Review.

Costrell, Robert M., Collin Hitt, and James V. Shuls. 2019. “A $19-Billion Blind Spot: State Pension Spending.” Educational Researcher.

Eide, Stephen D. 2015. “California Crowd-out: How Rising Retirement Benefit Costs Threaten Municipal Services (Civic Report No.98).” New York, NY: Manhattan Institute.

Griffith, Michael. 2012. “Understanding State School Funding.” The Progress of Education Reform. Vol 13(3). Denver, CO: The Education Commission of the States.

Kim, Dongwoo, Cory Koedel., and P. Brett Xiang. 2021. “The Trade-off between Pension Costs and Salary Expenditures in the Public Sector.” Journal of Pension Economics & Finance 20(1): 151–168.

Nation, Joe 2017. “Pension Math: Public Pension Spending and Service Crowd-Out in California, 2003-2030.” Policy Report. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research.

Public Plans Database. 2001-2024. Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, MissionSquare Research Institute, National Association of State Retirement Administrators, and the Government Finance Officers Association.

Randazzo, Anthony, Amy Dowell, and Nicki Golos. 2021. “Who Benefits? How Teacher Pension Financing Impacts Student Equity in Connecticut.” Research Report. Long Island City, NY: Equable Institute.

Randazzo, Anthony, Jonathan Moody, Max Marchitello, and Patrick Murphy. 2023. “Pension Debt Challenges for Equity in Education: The Effect of Teacher Pension Debt Costs on K–12 Education Funding in California.” Research Report. Equable Institute.

Schuster, Adam. 2018. “Tax Hikes vs. Reform: Why Illinois Must Amend Its Constitution to Fix the Pension Crisis.” Chicago, IL: Illinois Policy Institute.

Appendix

Endnotes

- 1For example, Nation (2017) finds that rising expenditures on pension benefits in California crowd out spending on higher education and social services. Others, like Eide (2015), believe payments towards pension costs are crowding out spending on core services such as police and fire.

- 2Anzia (2019) shows that, in response to a greater share of general revenue spent on rising pension costs, local governments reduce employment instead of raising revenue. The crowd-out of pensions on public services is more prevalent among local governments with collective bargaining. Schuster (2018) argues that public employment in Illinois fell in recent years due to growing pension costs. However, teacher hiring decisions may be different from those in local governments due to legal constraints such as class size mandates and the lack of ability for school districts to raise local revenue. Kim, Koedel, and Xiang (2021) find that higher teacher pension costs relate to lower salary expenditures through workforce reductions rather than salary cuts, but the coefficient is much smaller than Anzia (2019) and Schuster (2018).

- 3A review of the existing literature revealed a one-time survey in 2011 by Ron Snell at the National Conference of State Legislatures, a one-time member survey of retirement system administrators in 2015 by the National Association of State Retirement Administrators, and an academic study of Governmental Accounting Standards Board reporting requirements on states’ special funding arrangements in 2019 (see Costrell, Hitt, and Shuls 2019). Additionally, Randazzo, Dowell, and Golos (2021) focus on Connecticut, while Randazzo et. al (2023) investigate California.

- 4The following local teacher plans are included in the analysis: Denver Schools (CO), Chicago Teachers (IL), Omaha Teachers (NE), Minneapolis Teachers (MN), St. Paul Teachers (MN), Duluth Teachers (MN), Montgomery County Teachers (MD), Kansas City Teachers (MO), St. Louis Teachers (MO), New York City Teachers (NY), and Fairfax County Schools (VA). In many cases, the state government ends up explicitly providing some degree of regular funding for a local teacher plan because the local plan is merged into the state-run plan (e.g., Denver Schools merged into Colorado PERA, Duluth Teachers and Minneapolis Teachers merged into Minnesota TRA).

- 5While state education aid and state special funding arrangements for teacher pensions are often treated as separate legislative and budgetary processes within state and local governments, all money is fungible, and significant state-level pension contributions on behalf of school districts could reduce state resources available for other school district assistance.

- 6As of 2021, the Education Commission of the States finds that 34 states (including DC) determine costs on a per-student basis, 10 use a per-teacher basis, 6 use a hybrid of per student and teacher, and 1 relies on a guaranteed tax.

- 7This estimate is generally determined by the property values and income earned within each school district.

- 8While descriptive state-by-state summaries of state-aid programs are plentiful, they generally focus on the ways that aid is allocated across school districts. They rarely include any meaningful details on the way that estimates of the basic cost of education are derived and subsequently updated – let alone how pension costs are treated within that process.

- 9Griffith (2012) cites Arkansas, Maryland, and Wyoming as being among the few states that determine their foundation amounts through periodic studies conducted by third-party expert organizations. In many cases, early estimates of basic cost were based on existing school district expenditures and simply rolled forward afterward.

- 10Assuming no payroll growth, contributions grew 2.5 times from 2001 to 2024 (20/8 =2.5). Simply applying an annual 3-percent inflation increase would grow basic education costs by about 2 times over the same period [1.03^23=1.97]. So, if basic education costs supported 50 percent of pension costs in 2001, they would only support 40 percent of pension costs in 2024 [.5*1.97/2.5=.39].