What’s Going on with CBO’s Social Security Projections?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

The Agency’s Estimates Have Tripled in 7 Years Without Any Policy Changes

As a former chair of the Social Security Advisory Board’s Technical Panel, I am always interested in new projections of Social Security’s 75-year deficit. The 75-year deficit is the difference between the present discounted value of scheduled benefits and the present discounted value of future taxes plus the assets in the trust fund. The deficit can be interpreted as the amount by which the payroll tax rate would have to be increased to be able to pay the current package of benefits for everyone who reaches retirement age at least through 2090.

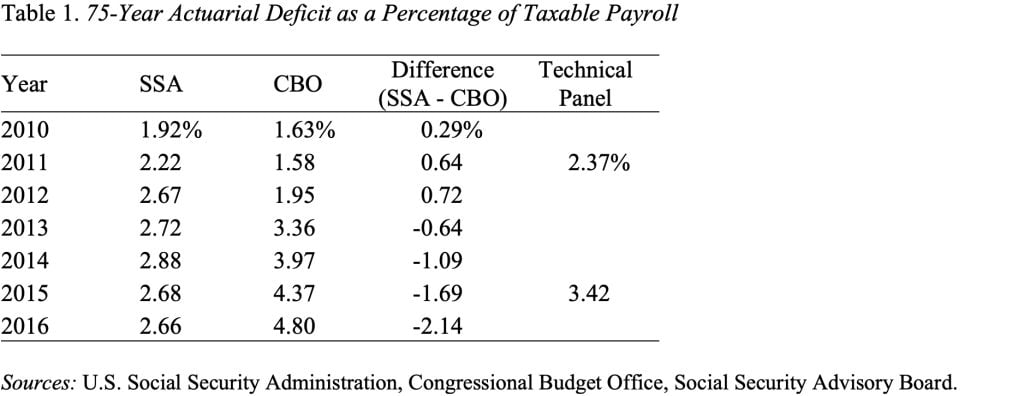

According to the Social Security actuaries’ latest estimate, the long-run deficit is projected to equal 2.7 percent of covered payroll earnings; the Technical Panel’s number is 3.4 percent; and the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) deficit is 4.8 percent.

The reasons that the Technical Panel’s number is 0.7 percentage points higher than the Social Security actuaries is threefold: a lower fertility rate, higher life expectancy, and a lower real interest rate. The higher assumed increase in life expectancy is not looking too good right now, as the data for recent years have actually shown a slowdown in the rate of improvement. And we might have been on the low side in terms of fertility. In any event, we called it as we saw it at the time, pulled no punches, and came out higher than the actuaries. Only time will tell who is right.

That said, I was knocked over by CBO’s new estimate of the 75-year deficit at 4.8 percent. The number is higher than the Technical Panel’s primarily due to worse economic assumptions. But the number looks strange, particularly when viewed in the context of the agency’s own previous estimates (see Table 1). What on earth has CBO learned since 2010 that would lead to a tripling of the deficit estimate?

Fortunately, the members of the public do not pay much attention to these numbers. If they did, they would think that Congress has no idea about the long-run costs and revenues associated with this program. Social Security financing is a fairly slow-moving phenomenon – not one where, without any policy changes, program costs triple.