Why Are Older Workers Shifting Jobs?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

The labor force participation of older workers has reversed its long-run decline. A larger share of this group wants to work longer. This shift reflects the changing incentives in Social Security and employer-sponsored plans, the improved education, health and longevity of today’s workers, less physically-demanding jobs, the need to wait for Medicare in the face of rapidly rising health care costs, and the joint decisionmaking of married couples. More older workers in the labor market is good news given the combination of a contracting retirement income system and increased life expectancy.

But another trend has also surfaced – older workers are increasingly moving from one job to another – and it’s not clear whether it is good news or bad news. One clear measure of that increased mobility is the decline in tenure. In 1983, average tenure of men age 55-64 was 15.3 years; by 2008 it had declined to 10.1 years. (I am focusing on 2008 rather than 2010 to separate long-term trends from the effect of the Great Recession.) Tenure was down across the board, but the decline among older workers was most pronounced.

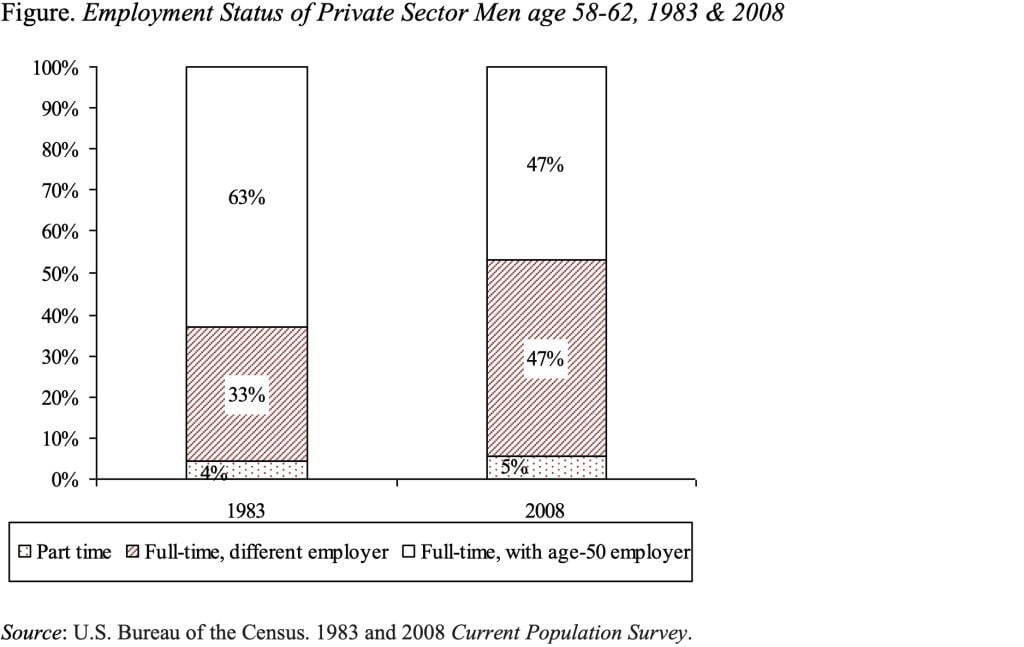

An even more direct way to show the decline in career employment is to see how many workers toward the end of their careers are still with the employer they had at age 50. The Figure classifies men 58-62 in 1983 and 2008 as: a) working full-time with the same employer as at age 50; b) working full-time with a different employer; or c) working part-time. The portion each year working part-time and working full time was virtually identical. But the distribution of full-time workers changed dramatically. In 1983, 63 percent of men 58-62 were with their age-50 employer; by 2008, that figure had dropped to 47 percent. Career employment is more common among workers with more education. But the shift away from career employment is consistent across educational groups.

Is the increased mobility voluntary? The short answer is we don’t know. On the one hand, data on displacement rates, which report layoffs for reasons other than job performance, have not increased for older workers. These data would suggest that separations of older workers are largely due to quits, not layoffs. The distinction between layoffs and quits, however, is not always clear. Employers can reduce a worker’s compensation or increase job demands.

Workers could also feel insecure in their current job, due to technological change or increased competition, especially from overseas. If workers quit in response to such pressures, they would be leaving on their own volition, but the decline of career employment could not be characterized as a positive development.

Is increased mobility of older workers helpful or harmful to working longer? The new jobs generally pay less and are less likely to offer pension and health insurance coverage. This fall in wages and benefits makes continued employment less attractive vis-à-vis retirement. On the other hand, workers who shift jobs often report less stress and an increase in job satisfaction that makes work more attractive vis-à-vis retirement. The fall in wages and benefits also reduces household wealth, and this “wealth effect” also encourages continued employment. How workers respond depends on the strength of these various effects.

While the long-term impact of older workers shifting jobs is ambiguous, the short-term implications are not. The average duration of unemployment for those in their 50s is now more than a year. Older workers are safer with their current employer than scurrying around the labor market trying to find a new job.