Why Do Politicians Keep Running Up the Debt?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Future retirees will pay with lower Social Security and Medicare benefits.

Most people think that the budget deal between congressional leaders is a positive development. One’s assessment depends critically on “compared to what.” Yes, it eliminated the threat of both an unprecedented default by the U.S. government on its debt and deep budget cuts that would have been triggered under the Budget Control Act. But the agreement did not include a single additional dollar in revenue, either from raising tax rates or eliminating tax loopholes.

The deal between congressional Democrats and the White House, which has also been approved by the Senate, would raise the budget caps by an average of about $160 billion annually for the next two years and would lift the debt limit for an estimated two years. The Democrats are happy because they avoid $150 billion in spending cuts that the Trump Administration was demanding to raise the debt ceiling. (The bill does include $55 billion in spending cuts, but these take place over ten years, by which time Congress can overturn them.) The Republicans are happy because they got more funding for the military. Presumably members of both parties are happy to avert a default on the U.S. debt.

This is really a crazy way, however, to run a nation’s finances. Even in a period of low interest rates, it seems sensible to pay for things we consume this year with taxes raised this year and to reserve debt financing for expenditures that will provide benefits over multi-year periods, such as infrastructure. Paying for current expenditures particularly makes sense when the economy is operating at full employment and does not need any fiscal stimulus.

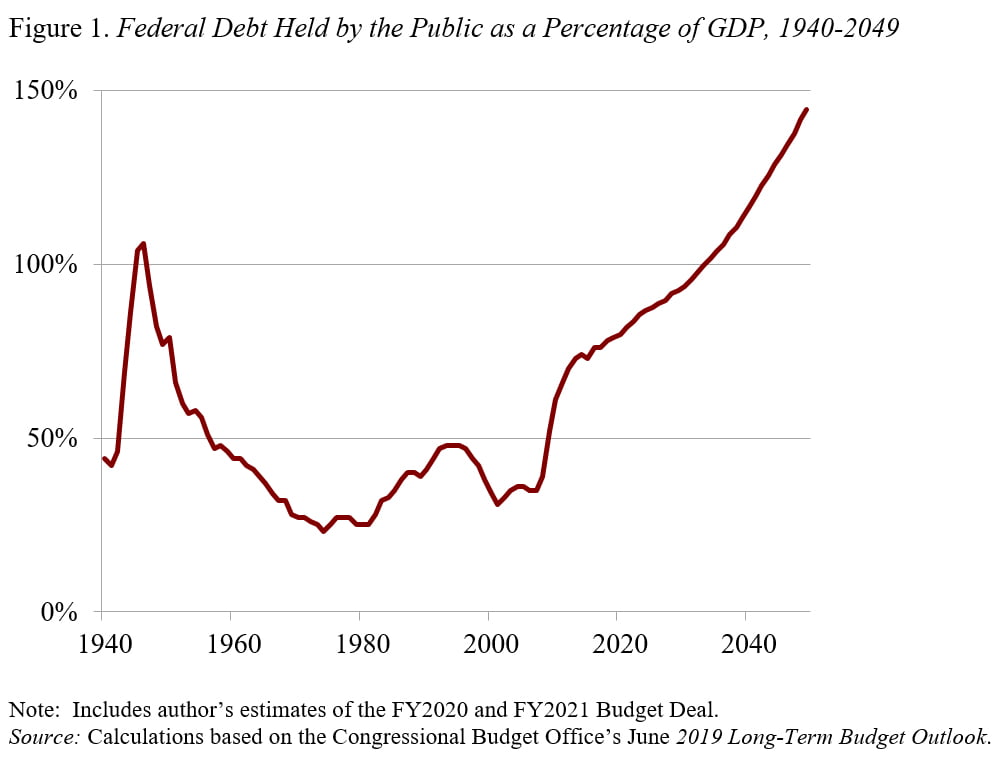

The debt limit is a silly provision. All decisions about the nation’s debt arise from the spending and tax programs adopted by Congress. If Congress wants to limit the debt, it should reinstate the pay-go rules that require either additional taxes or reduced spending to offset any new initiative. The existing debt ceiling provides no discipline but merely serves as a catalyst for periodic crises. So while the budget deal may be the least bad outcome in the current environment, it is not good for the nation’s long-run fiscal health. According to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, the plan will increase discretionary spending over the next two years and, when combined with interest on the new debt, add $1.7 trillion to projected budget levels over the next decade. Combine the new debt-financed spending with the revenue loss from the 2017 tax cut, and the nation is projected to soon exceed the debt-to-GDP ratio it reached at the end of World War II (see Figure 1).

The big losers, just as in the case of the 2017 tax cuts, are future taxpayers and middle-class families. Since I focus on retirement, my primary concern is the pressure that the deteriorating fiscal picture will put on the programs middle-class families rely upon when they stop working – namely, Social Security and Medicare. The same politicians who seem to have no problem with putting tax cuts and additional spending on the nation’s credit card will surely cry poverty when the time comes to shore up the nation’s crucial social insurance programs.

In fact, when asked about how the government will deal with the federal budget deficit, Mitch McConnell said that entitlement programs are the “long-term driver of debt.” He added that in order to keep Social Security and Medicare in balance for the next generation, we know we must do something significant on age adjustment or means-testing at some point.

Seriously?