Why You’ll Probably Have a Worse Retirement than Your Parents Did

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

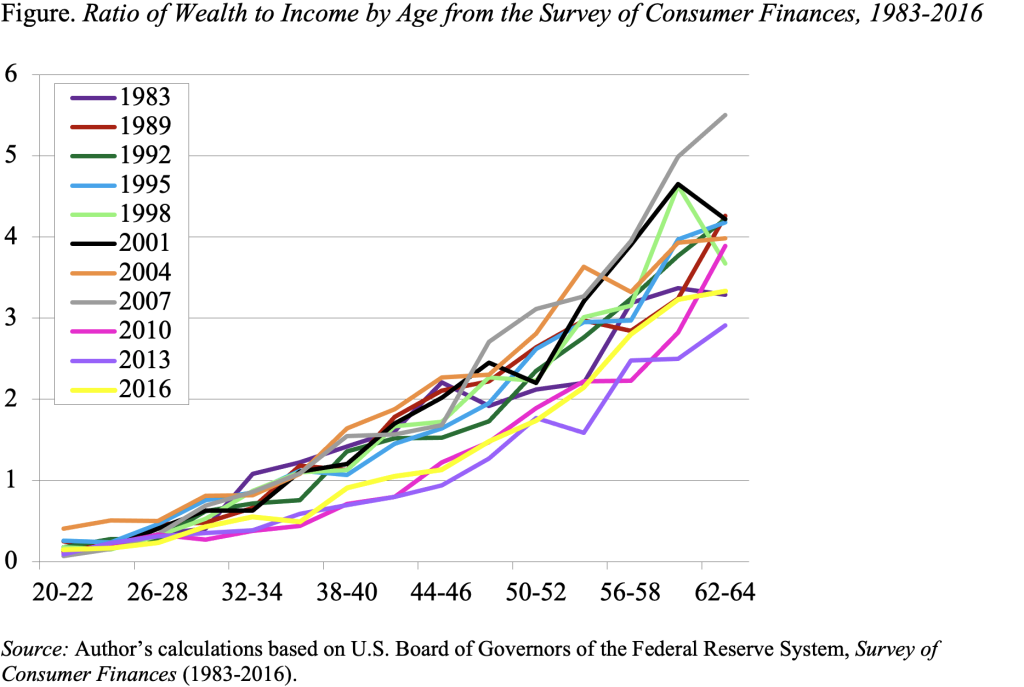

Wealth-to-income ratios have not increased over time despite the need to save more.

People often ask how well prepared for retirement are current workers compared to their parents. One way to answer that question is to look at the ratio of wealth to income over time from the Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), which is conducted by the Federal Reserve every three years. The notion is that the wealth-to-income ratio is a good proxy for the extent to which people can replace their pre-retirement earnings in retirement.

The figure shows the ratio of wealth to income by age for each SCF from 1983 through 2016. The general pattern is that wealth equals about one times income at ages 32-34 and rises to about four times income at ages 62-64. Wealth includes all financial assets, 401(k) accumulations, and real estate less any outstanding debt. Income includes earnings and returns on financial assets.

Do not try to distinguish among the individual lines. The point of the chart is that the ratios for each age from each survey lie virtually on top of one another – if anything, ratios in recent years have been on the low side.

A virtually unchanged ratio may sound comforting, but it is actually alarming because people should be saving more for several reasons:

- People are living longer and spending more time in retirement – three years longer for the average man.

- Retirees face high and rising healthcare costs, so they need more assets to cover out-of-pocket medical expenses.

- Interest rates have declined, so retirees need a larger nest egg to achieve any given level of income.

- Social Security benefits have become less generous, so people need to save more.

- Finally, the shift away from traditional pension plans – which are not included in the Fed’s data – to 401(k)-type plans – which are included – should have caused the reported wealth-to-income ratio to rise, but it did not.

In the face of these developments, the stability of wealth-to-income ratios strongly suggests declining retirement security. Younger baby boomers and the generations that follow will be even more vulnerable if Social Security benefits are cut to address the program’s long-term financing shortfall.