Will Older Individuals Avoid Nursing Homes After the Pandemic?

The brief’s key findings are:

- In many countries, a large share of COVID deaths in the first wave occurred in nursing homes.

- As a result, the pandemic focused attention on health risks in nursing homes that might lead some to prefer home care.

- A survey of Canadians ages 50-69 found that:

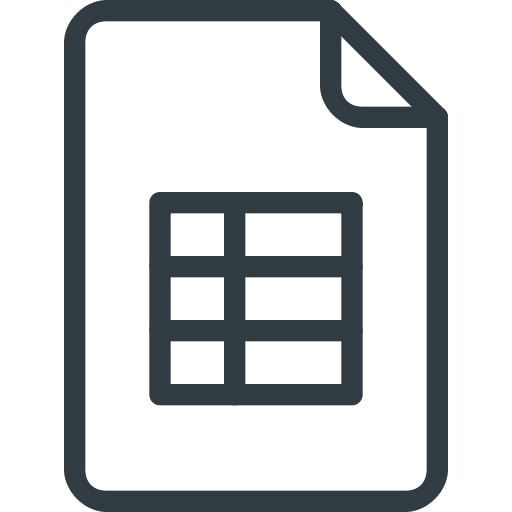

- 70 percent said they are less likely to use a nursing home post-pandemic;

- one-quarter are willing to save more to pay for home care; and

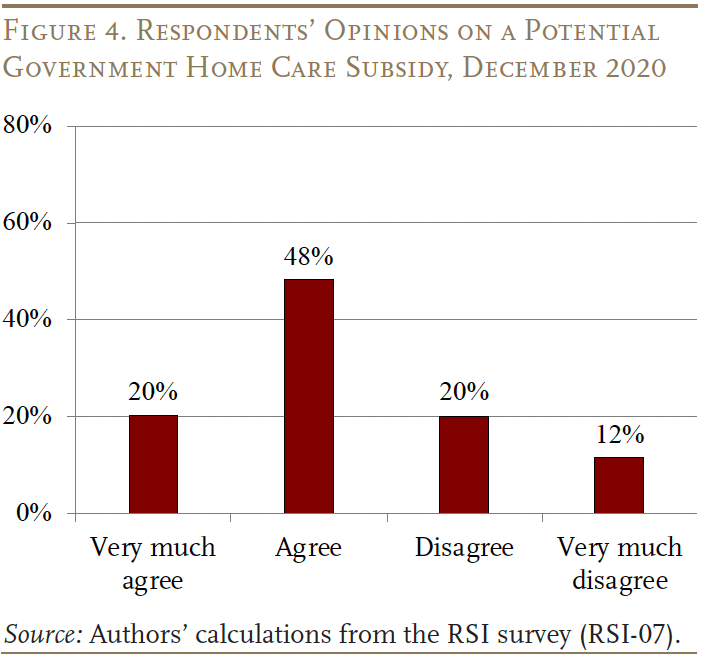

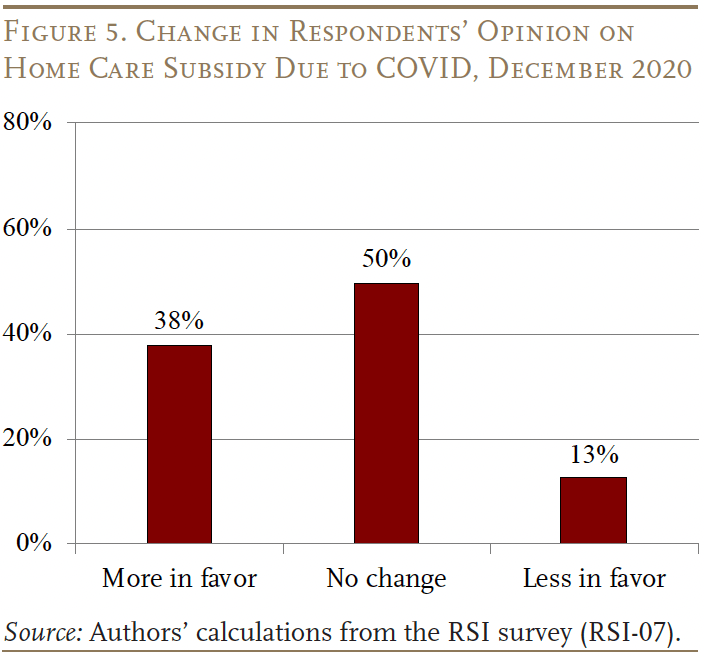

- the vast majority favor more government subsidies for home care, even if it requires higher taxes.

- Given the broad similarities between Canada and the United States, these overall results likely apply to the U.S. context as well.

Introduction

In Canada, as in the United States, a large share of COVID deaths during the first wave occurred in nursing homes.1See Ontario Ministry of Health (2022a) for Ontario and Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec (2022) for Québec. As a result, the pandemic shed light on lax infection control practices and lack of staff in some nursing homes. In both countries, the extensive media coverage of these issues may have a lasting impact on older individuals’ choices of long-term care. That is, more people might decide to receive care in their own homes instead of entering a nursing home, even when COVID is no longer as serious a threat. If so, a related question is how such home care would be financed, given that both countries more readily subsidize nursing home care compared to home services.

This brief, adapted from a recent study, assesses the reaction of Canadians to nursing homes in the wake of COVID. This assessment is based on an online survey of a representative sample of residents in Ontario and Québec who are ages 50-69.2Achou et al. (2022).

The discussion proceeds as follows. The first section provides background on nursing homes and COVID. The second section summarizes the survey methodology. The third section presents the results, which reveal that more than 70 percent of respondents are less inclined to enter a nursing home than before the pandemic; about one-quarter are willing to save more for home care services; and the vast majority favor increased government subsidies for home care, even if financed by higher taxes. The final section concludes that, given the broad similarities between Canada and the United States, the main results are likely applicable to older Americans as well.

Background

In many countries, including Canada and the United States, COVID deaths have been heavily concentrated among older people. And, early in the pandemic, these deaths largely occurred in nursing homes. For example, by May 2020, more than 90 percent of the COVID deaths among individuals ages 70+ in Québec were in nursing homes, while in Ontario, it was more than 70 percent.3Ontario Ministry of Health (2022a) and Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec (2022). In addition, many nursing home workers left during COVID due to the more challenging conditions, which meant the remaining nursing home residents faced an increasing health risk and worse living conditions. Since these issues received widespread media coverage, they were very visible to the public and may have a lasting impact on individuals’ choices between entering a nursing home or receiving care in their own home.

Many countries, however, provide more generous public subsidies to nursing-home care than to home care. In Ontario, for example, the maximum monthly cost of entering a semi-private room in a public nursing home was 2,280 CAD in 2019.4Ontario Ministry of Health (2022b). Moreover, individuals are eligible for subsidies depending on their financial situation, which reduces the effective cost of entering a nursing home. On the other hand, the cost of one hour of skilled nursing care at home varied between 23 and 70 CAD in 2018, depending on the type of care required.5Canadian Health and Life Insurance Association (2018). So, for the 2,280 CAD monthly cost of a nursing home, an individual could afford only about two hours per day of home care (assuming a home care cost of 35 CAD). In addition, expenses for food, house maintenance, and utility bills, which are typically included in a nursing home fee, make home care even more costly. Thus, people who plan to use home care instead of entering a nursing home might need to save more on their own unless the government provides more subsidies for home care.

Data

The results in this brief are from an online survey conducted in partnership with Asking Canadians, an online panel survey organization.6This survey was a part of the regular web surveys conducted by the Retirement and Savings Institute (RSI) at the HEC Montréal. The survey was fielded to residents of Ontario and Québec in December 2020, more than half a year after the first wave of the pandemic. To be eligible, the respondent had to be ages 50-69 without any limitations on activities of daily living, as the survey focuses on the impact of the pandemic on their future plans for long-term care instead of current use. In total, 3,004 respondents completed the survey. Sampling weights are constructed so that the weighted sample has characteristics similar to a representative sample from the 2016 Canadian Census. Key survey questions are described, along with the results, in the next section.

Results

The survey finds that most older Canadians have an aversion to entering a nursing home after observing the issues at those institutions during the initial phase of the pandemic. The survey asked the respondents whether they are more, less, or similarly inclined to enter a nursing home compared to what they thought before the pandemic, if they need long-term care in the future. More than 70 percent of the respondents reported being less inclined to enter a nursing home after the pandemic, while a quarter reported no change in their long-term care plans (see Figure 1).

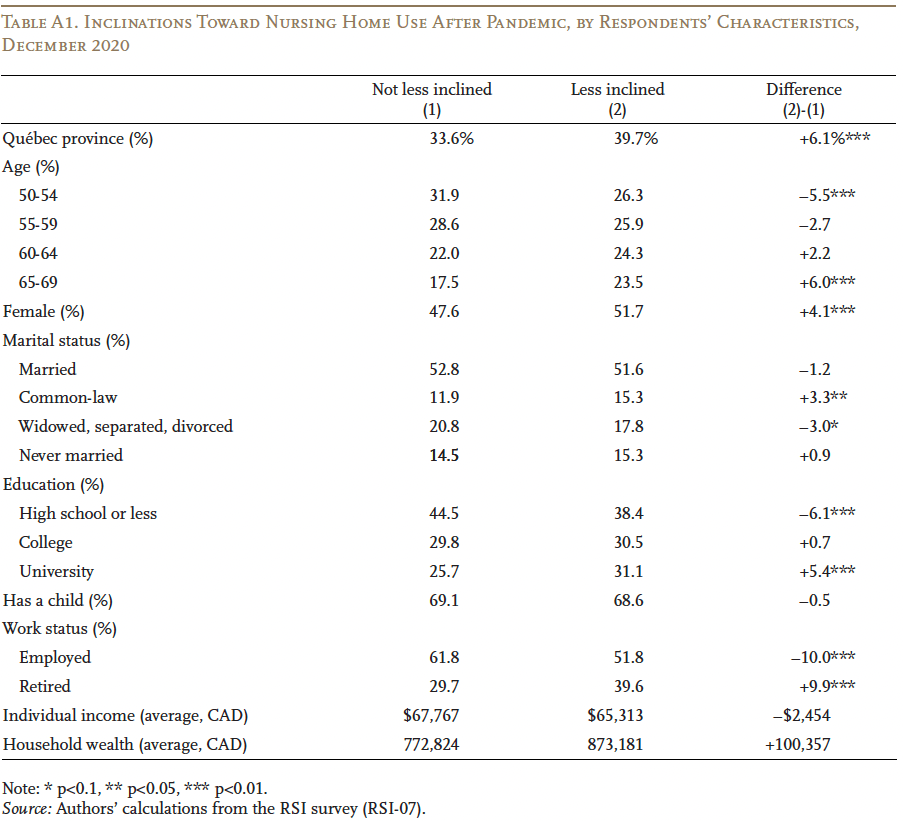

Nursing home aversion is widespread across demographic groups. Those less inclined to enter a nursing home after the pandemic and those who are not are largely similar, with some statistically significant differences. For example, those less inclined to enter a nursing home are more likely to be residents of Québec, older, female, and have a university degree; but these differences are relatively small (see Appendix Table A1).

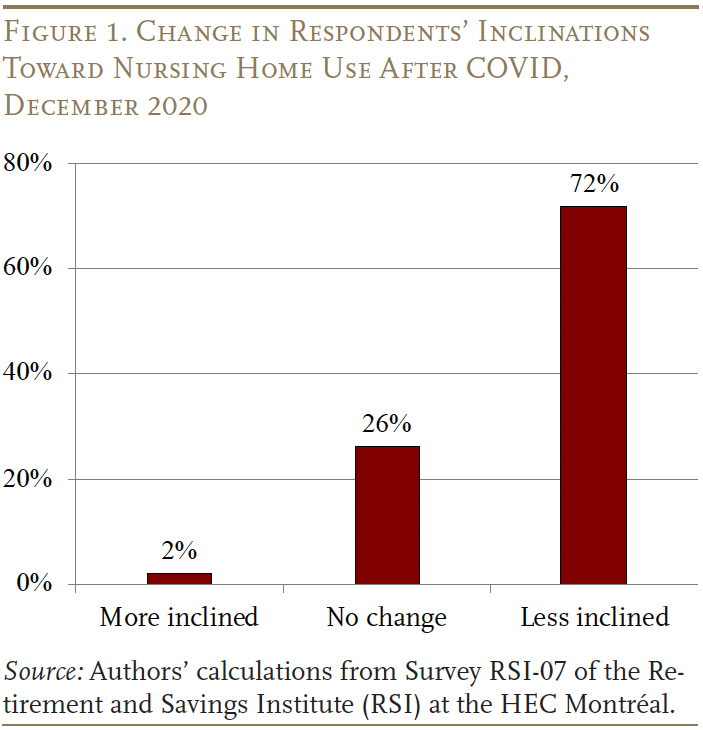

Not surprisingly, nursing home aversion is associated with greater concerns about the exposure to health risks at nursing homes. About 70 percent of respondents reported that the pandemic negatively impacted their views on public nursing homes (see Figure 2). The distribution of the responses is almost identical for the views on private nursing homes.

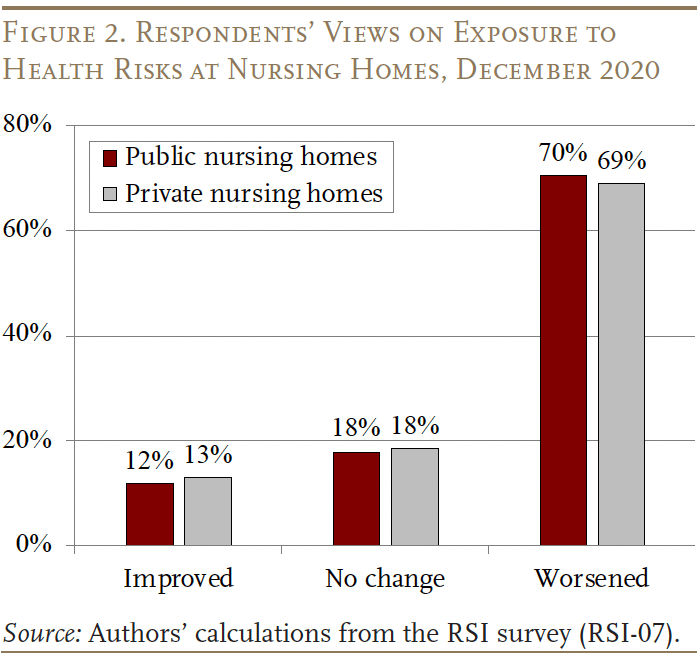

While respondents are clearly more concerned about nursing homes, some are also aware that planning to use home care instead may require more resources. More than a quarter of the respondents reported being willing to save more post-pandemic (see Figure 3). For this group, the survey further asked whether they would save more to avoid entering a nursing home when they need long-term care; and 83 percent said yes.

If individuals are mainly responsible for covering the risk of needing late-life home care, it could pose an excessive burden. Therefore, those who plan to use home care may support new public policies to subsidize home care. To explore this issue, the survey asked: “Suppose the government was to propose a policy to increase the access to home care for people needing help with activities of daily living…to reduce their likelihood of going to a nursing home, but would increase taxes to finance this policy. What…would be your opinion…?”

The results show strong support for such a policy. About 70 percent agree with the home care subsidy funded by higher taxes, with 20 percent strongly agreeing (see Figure 4). Only 12 percent strongly disagree with such a policy.7Strong disagreement with a home care subsidy is not concentrated among particular income or wealth groups, nor is it noticeably correlated with nursing home aversion. It is possible that it represents a group of people who are generally skeptical about the ability of the government to effectively meet health and welfare needs, though the survey did not cover this issue.

The survey also asked whether the pandemic has changed their opinion on a home care subsidy. The result confirms that the pandemic strengthened support for such a policy. About 40 percent reported that they are more in favor of a home care subsidy compared to before the pandemic, and only about 10 percent are less in favor post-pandemic (see Figure 5).

Conclusion

Many Canadians reported that they are more likely than before to shun nursing homes after observing the initial wave of COVID outbreaks and substandard living conditions in some nursing homes. However, home care services equivalent to nursing home care tend to be significantly more costly in Canada, so more generous government home care subsidies may be needed to reduce the difference.

The survey responses in this brief demonstrate strong support for such policies among the older population. The United States has had similar experiences with nursing homes during COVID and also tends to more readily subsidize institutional care over home care. Thus, the survey results likely apply to the U.S. context as well, suggesting that policies aimed at making home care more affordable might better meet the preferences of older Americans in the wake of the pandemic.

References

Achou, Bertrand, Philippe De Donder, Franca Glenzer, Minjoon Lee, and Marie-Louise Leroux. 2022. “Nursing Home Aversion Post-pandemic: Implications for Savings and Long-term Care Policy.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 201: 1-21.

Canadian Health and Life Insurance Association. 2018. “Canadian Life and Health Insurance Facts.” Toronto, Canada.

Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec. 2022. “Données COVID-19 au Québec.” Québec City, Canada.

Ontario Ministry of Health. 2022a. “Case Numbers, Spread and Deaths.” Toronto, Canada.

Ontario Ministry of Health. 2022b. “Long-term Care Homes.” Toronto, Canada.

Appendix

Endnotes

- 1See Ontario Ministry of Health (2022a) for Ontario and Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec (2022) for Québec.

- 2Achou et al. (2022).

- 3Ontario Ministry of Health (2022a) and Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec (2022).

- 4Ontario Ministry of Health (2022b).

- 5Canadian Health and Life Insurance Association (2018).

- 6This survey was a part of the regular web surveys conducted by the Retirement and Savings Institute (RSI) at the HEC Montréal.

- 7Strong disagreement with a home care subsidy is not concentrated among particular income or wealth groups, nor is it noticeably correlated with nursing home aversion. It is possible that it represents a group of people who are generally skeptical about the ability of the government to effectively meet health and welfare needs, though the survey did not cover this issue.