Will “Unretirement” Solve the Labor Shortage?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Unlikely, says a new study.

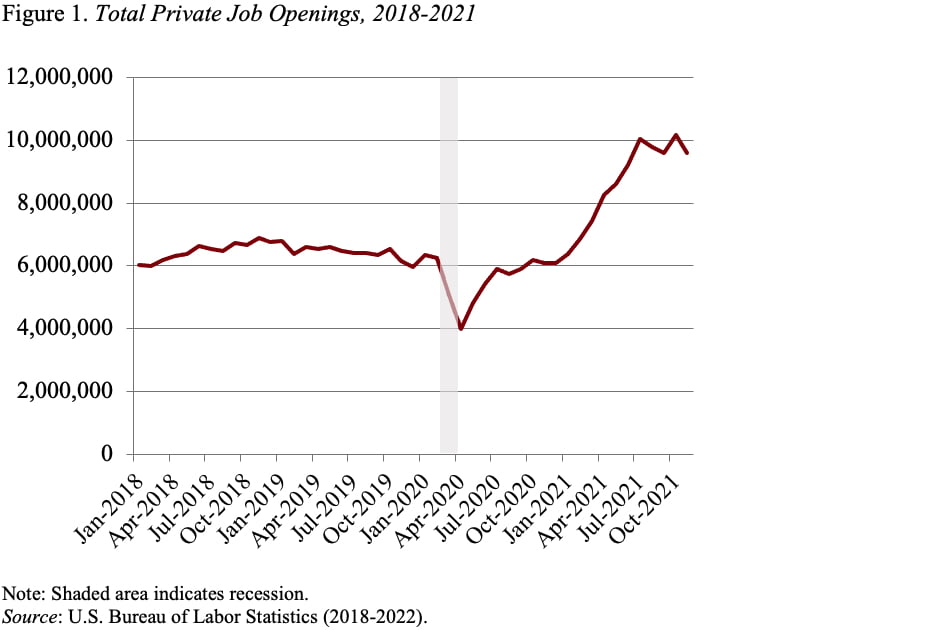

The United States is currently facing an unprecedented labor shortage; job openings that ran at 6 million before the pandemic are now hovering at 10 million (see Figure 1).

At the same time, a large pool of people ages 55-70 – over 15 million today – indicate they are retired. The potential return of a lot of these people would go a long way to solving the problem.

To evaluate the likelihood of mass “unretirement,” in a forthcoming study, my colleagues Geoff Sanzenbacher and Matt Rutledge explore the extent to which retired individuals reentered the labor force over the last several decades, and how their response varied by labor market conditions.

They used the March Annual Social and Economic Supplement to the CPS to follow workers ages 55-70 from a year when they were retired into the next year to see if they rejoined the ranks of the employed. They then used this info to construct an “unretirement rate.”

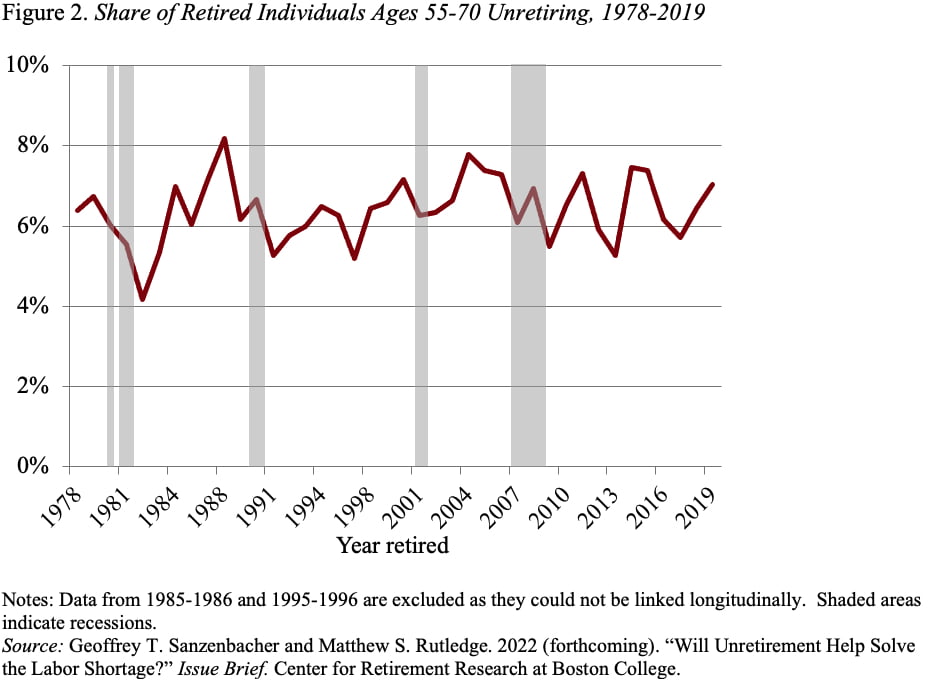

Figure 2 shows that the rate of unretirement has been relatively low over the last four decades, averaging just over 6 percent, and responds very little to recessions and expansions.

To get a more precise measure of the responsiveness of unretirement to economic conditions, they also estimated a regression that related the unretirement rate to the job opening rate at the state level, controlling for other factors that could affect re-entry, such as education, age, gender, and Social Security receipt.

They found that an increase in the job opening rate had a relatively small, albeit statistically significant, effect on unretirement. Specifically, a 1-percentage-point increase, year-over-year, in a state’s job opening rate increased unretirement by 0.5 percentage points. The other coefficients in the equation imply that relatively younger workers, more educated workers, and men are more likely to reenter employment than others.

Given today’s high job opening rate, the results suggest that we could expect 1.9 percent more workers to unretire than typically would during an economic recovery. With 15 million workers ages 55-70 currently retired, an increase of 1.9 percentage points would represent about 300,000 additional workers. Thus, unretirement would solve less than one tenth of the 4-million worker shortage – a non-trivial fraction but not a solution to the shortage either.

The authors close with the possibility that things might break to the high side in view of the large-scale change in working conditions, particularly the ability to work remotely. If the ability to work remotely makes employment more attractive, the unretirement rate could be larger than anticipated based on past experience.