2019 Survey of Consumer Finances Shows Modest Increase in 401(k)/IRA Balances

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

But holdings remain low, and many households have none.

The Federal Reserve recently released the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), a triennial survey of a nationally representative sample of U.S. households, which over-samples those with high net worth. It is considered the gold standard of information on income and wealth. For American households, both median income and median earnings and wealth increased since 2016.

But retirement is our game, so we turned immediately to combined 401(k)/IRA balances – particularly for those approaching retirement. The great advantage of the SCF is that it provides information not only on 401(k) balances, much of which is available from financial services firms, but also on household holdings in IRAs. While 401(k) plans serve as the gateway for retirement saving, more than half of the money collected now resides in IRAs. The relevant question is how much do households nearing retirement hold in these two sources combined.

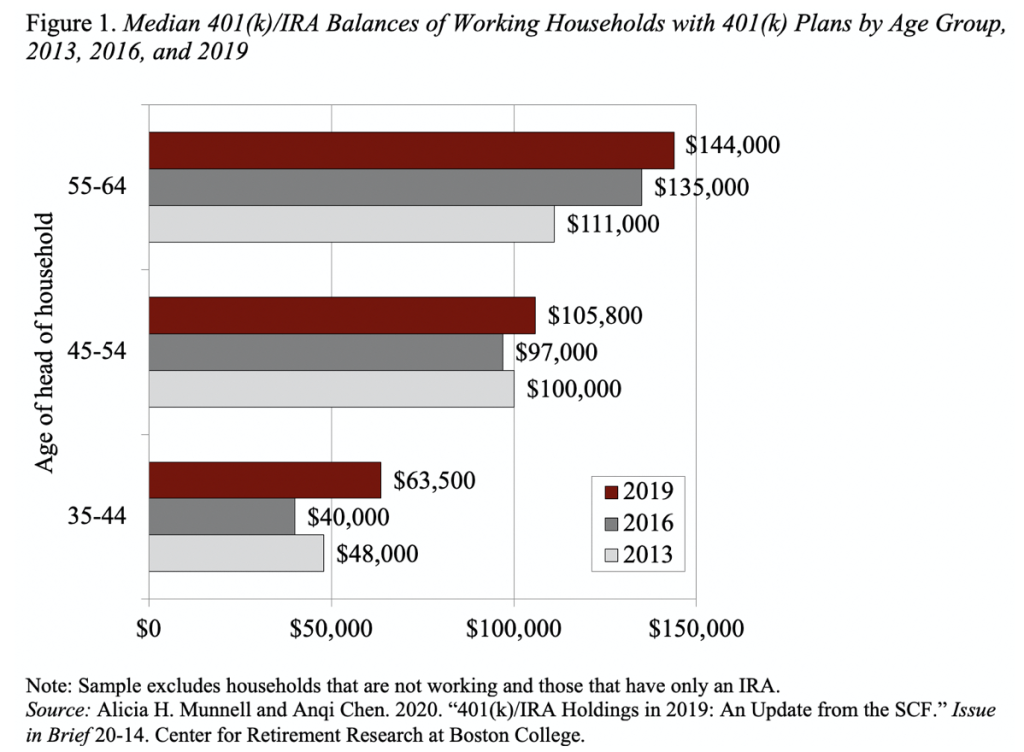

The 2019 SCF shows that, for the typical working household ages 55-64 with a 401(k), 401(k)/IRA balances increased to $144,000 from $135,000 in 2016 (see Figure 1). That seems like a modest increase given that the Dow Jones Industrial Average rose by about 50 percent over the three-year period.

If a couple uses their $144,000 to buy a joint-and-survivor annuity, they will receive $570 per month in retirement. Since this amount is not indexed for inflation, its purchasing power will decline over time. And this $570 is likely to be the only source of income beyond Social Security, because the typical household holds virtually no financial assets outside of its 401(k).

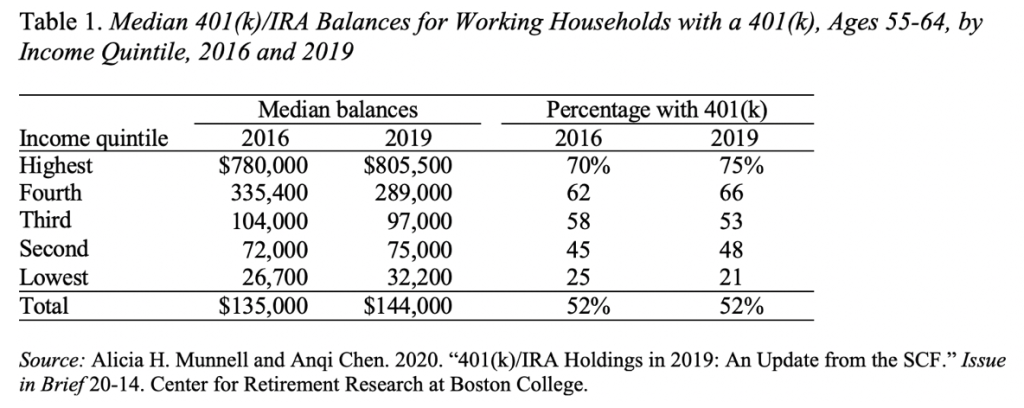

While the median for households approaching retirement was $144,000, the amount and pattern of increase varied significantly by income. Balances for the highest quintile were $805,500 in 2019, and the share of high-income households with 401(k) balances rose to 75 percent (see Table 1). In contrast, for the lowest quintile, balances amounted to only $32,200 and the percentage of households with a 401(k) declined from 25 percent to 21 percent.

These results from the most recent SCF reinforce the concern that retirement accounts appear to serve as a meaningful source of saving only for the upper two quintiles. Those in the lower 60 percent of the income distribution end up with either nothing other than Social Security or very small balances. This pattern reflects the fact that workers do not have continuous coverage in our employer-based retirement system. Policymakers need to address this problem. They must require that employers either provide a plan themselves or auto-enroll their employees in a retirement savings program initiated by government. Burgeoning auto-IRA programs at the state level – in California, Illinois and Oregon – are a first step down this path. But we need a nationwide auto-IRA program.