401(k) Balances Increased Very Little in the Last 10 Years

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Auto-enrollment without auto-escalation of default contribution rate is part of the problem.

One of my favorite publications just came out: “How America Saves.” This annual report from Vanguard summarizes the statistics for the defined contribution plans that the company administers. Vanguard tends to administer larger plans, so the plans are better designed than average and participants have higher incomes. In other words, it presents the best face of the 401(k) system.

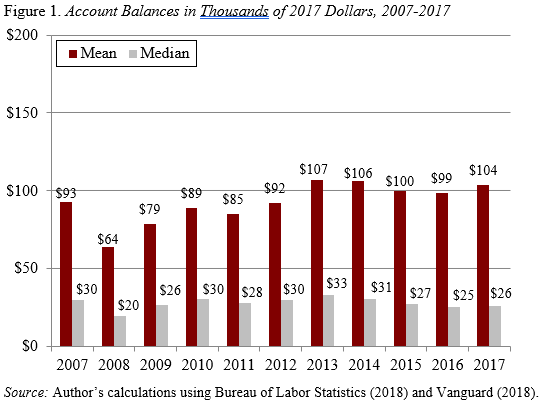

In 2017, the average account balance was $103,900; the median was $26,300. The big difference between the median and the average is due to a small number of accounts that have really big balances. Average balances are more typical of long-tenured more affluent participants, while the median balance represents the typical participant. 2017 was a good year in the stock market – the average participant’s return was 18 percent – which explains the uptick in balances from 2016.

Despite the recent uptick, a longer-run perspective raises troubling questions. Figure 1 shows average and median balances for the last eleven years in 2017 dollars. In terms of medians, 2017 is actually lower than 2007. This pattern could well reflect the expansion of auto-enrollment, which increases participation but also produces smaller balances. That is, more people save, but the accumulations are smaller because employees are typically enrolled at a default contribution rate of 3 percent.

The fact that the average account balance in 2017 was only $11,000 higher than that in 2007 is more concerning, since, as discussed, a relatively small number of large accounts affects this number. However, this pattern could be explained by the age distribution of the participants since the percentage of young participants, who have small balances, has increased over time.

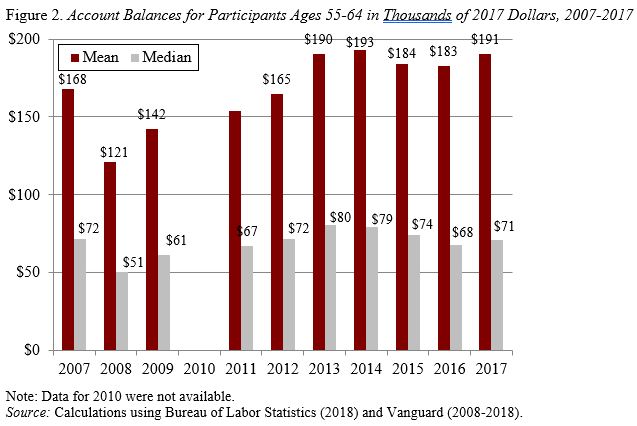

To get away from the impact of more young participants, it’s useful to look at balances for those ages 55-64, a group approaching retirement. As one would expect, these balances are nearly twice as large as those for the participant population as a whole. But the pattern is quite similar: 2017 median balances are lower than those in 2007, and average balances are up by $22,000.

The data on balances suggest that we have not made a lot of progress in terms of 401(k) saving. And Vanguard balances are probably higher than average given that it administers a large number of big plans. On the other hand, many people approaching retirement have moved some 401(k) balances over to Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs). In 2016, the date of the latest Federal Reserve Survey of Consumer Finances, the median 401(k)/IRA holdings of working households with a 401(k) approaching retirement (55-64) were $135,000. So the picture is somewhat less bleak than the Vanguard data alone would suggest. Bleak, nevertheless.

The one immediate policy implication suggested by these numbers is that auto-enrollment without auto-escalation may well do more harm than good. If people are auto-enrolled at a 3-percent contribution rate, they are likely to stay with that rate. They may be worse off than if they were allowed to enroll at a later date on their own with an average contribution rate. My choice would be to make auto-enrollment and auto-escalation mandatory for all 401(k) plans, starting at a default contribution rate of 6 percent that rises gradually to 10 percent.

Clearly changes are needed if 401(k) plans are going to be an effective savings mechanism.