COLA Cuts in State and Local Pensions

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Defined benefit promises in the public sector are not as secure as many thought.

One of the more surprising responses of public plan sponsors to the financial crisis and the ensuing recession was their reduction, suspension, or elimination of cost-of-living adjustments (COLA) for current workers and, in a number of cases, current retirees. The response was surprising because it has often been assumed that public plan participants have greater benefit protections than their private sector counterparts. The Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA), which governs private pensions, protects accrued benefits but allows employers to change the terms going forward. In contrast, most states have legal provisions that constrain sponsors’ ability to make changes to future benefits for current workers. Yet they were able to change the COLA for current workers and often for people already receiving it.

Between 2010 and 2013, seventeen states (with a total of 30 plans) enacted legislation that reduced, suspended, or eliminated COLAs for current workers and often for current retirees. The cuts fell into three groups:

- Three states with seriously underfunded plans – New Jersey, Rhode Island, and Oklahoma – essentially eliminated the COLA for the foreseeable future.

- Eight states that provided a guaranteed fixed percentage increase each year regardless of inflation – Colorado, Florida, Illinois, Minnesota, Montana, New Mexico, Ohio, and South Dakota — either reduced or temporarily suspended the guarantee or shifted to a Consumer Price Index (CPI)-linked COLA.

- Six states with CPI-linked COLAs – Connecticut, Maine, Maryland, Oregon,

Washington, and Wyoming – made changes, mainly by reducing minimum or maximum adjustments or linking COLAs to the plan’s funded status or the participant’s benefit level.

Four states that cut their COLA – Colorado, Illinois, Maine, and Ohio – have plans where workers are not covered by Social Security. If inflation rises to 3 or 4 percent, participants in all four states will see the real value of their entire retirement income erode.

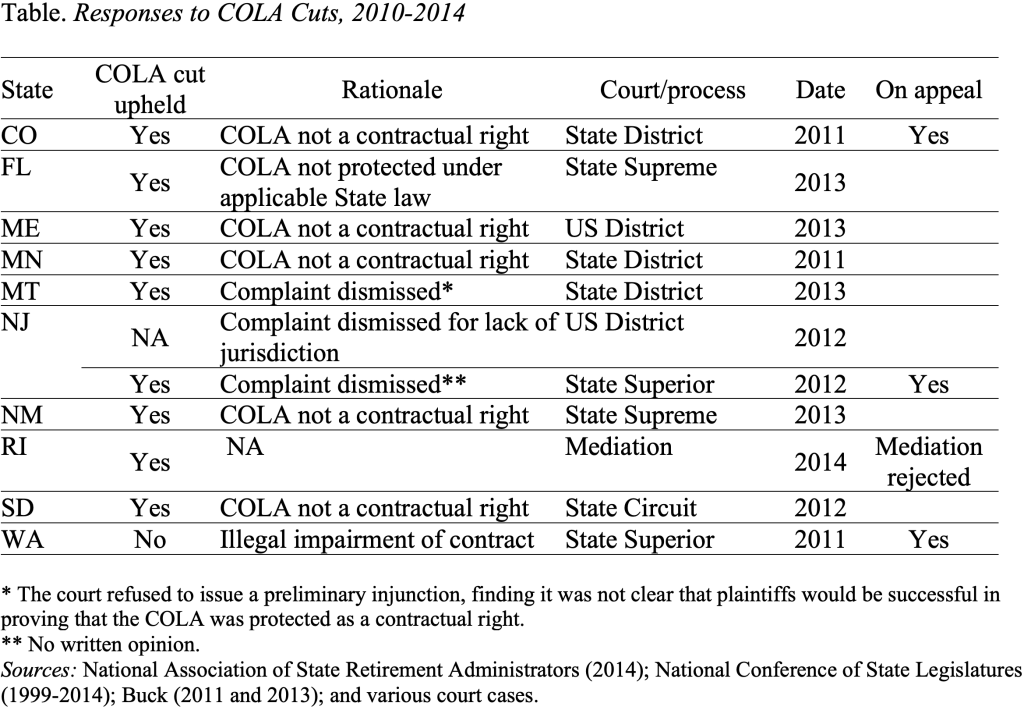

Of the 17 states that changed their COLA, 12 have been challenged in court. The courts have ruled in nine states and in all but one case have upheld the cut. The Rhode Island proposals to cut the COLA withstood the mediation process with only minor changes but police union members subsequently rejected the mediation agreement. The Table summarizes the status of these suits. Suits have been filed in Illinois and Oregon, but no decisions have been reached.

The main rationale for allowing the COLA cut is that COLAs are not considered to be a contractual right. For example, in Colorado, where the decision is currently under appeal, the judge found that the plaintiffs had no vested contract right to a specific COLA amount for life without change and that the plaintiffs could have no reasonable expectation to a specific COLA amount for life given that the General Assembly changed the COLA formula numerous times over the past 40 years. In Minnesota, the judge ruled both that the COLA was not a protected core benefit and that the COLA modification was necessary to prevent the long-term fiscal deterioration of the pension plan. The Courts clearly view COLAs very differently than core benefits. At this point, the legal hurdles to cutting COLAs appear to be quite low.