Let’s Fix Social Security Now!

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

We’re already 20 years behind

This is as good a time as any to fix Social Security’s financing problems. In fact, Congress’s decision to allow the 2-percentage-point reduction in the payroll tax to expire as part of the fiscal cliff negotiations clears the path for restoring full solvency. Of course, Social Security has not contributed to the deficit in the past and technically cannot in the future because, by law, expenditures cannot exceed earmarked revenues. But, Social Security’s promised benefits exceed scheduled taxes, creating a financing shortfall that needs to be fixed.

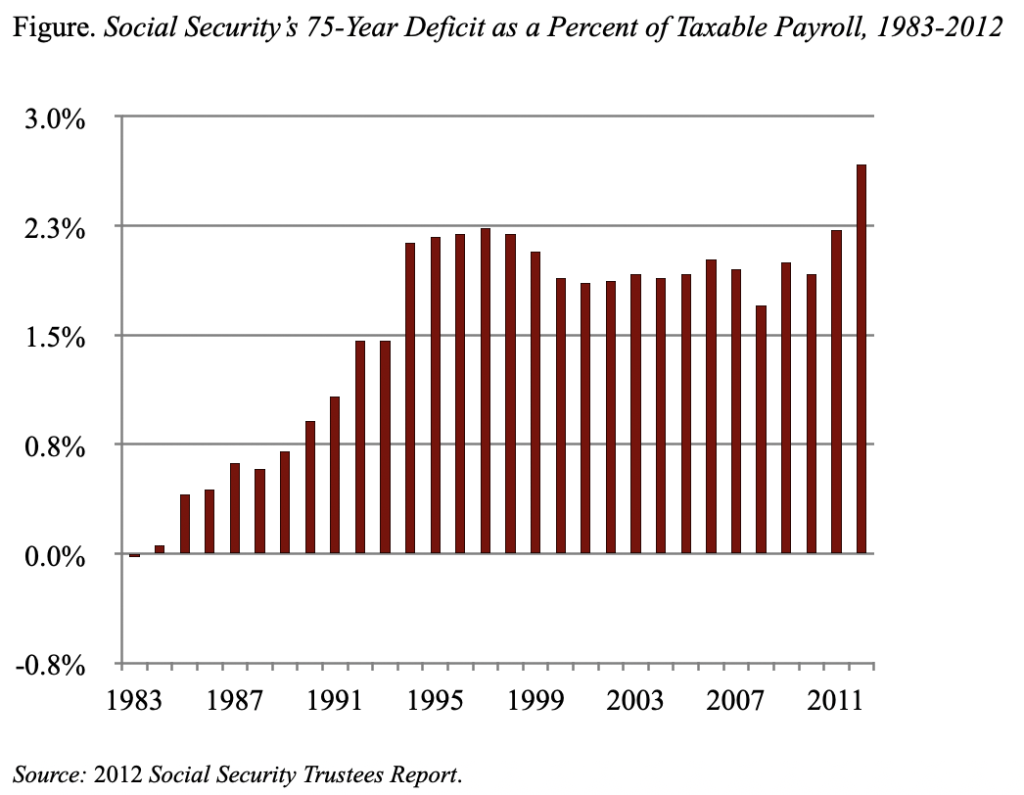

The political climate is daunting for any sensible endeavor. But I can’t think of any reason why next year will be better than this year. And we are coming up on the 20th anniversary of evidence of a significant shortfall in the program. I am particularly sensitive to the date because in 1994, as assistant secretary of treasury for economic policy, I was handed a draft of the trustees report showing a jump in the long run deficit from 1.5 percent to 2.1 percent of taxable payrolls (see Figure). As a big supporter of this wonderful program, I was dismayed to have the deterioration in the system’s finances occur on my watch.

Restoring balance to Social Security is crucial for the well-being of every worker, because Social Security provides the base of retirement income. The benefits are not large – about $1,200 per month on average – but they are indexed for inflation and continue as long as people live. The only other retirement income for most households will be that produced by assets in 401(k) plans. The Federal Reserve’s recent Survey of Consumer Finances shows that these assets are modest – $120,000 for households approaching retirement. If a couple purchases a joint-and-survivor annuity, they will receive $575 per month. This $575 is likely to be the only source of additional income, because the typical household holds virtually no financial assets outside of its 401(k) plan.

The key question is how much of Social Security’s financing gap should be closed by cutting benefits vs. raising taxes. My view is that retirements are at risk. The need for retirement income is increasing as people are living longer, health care costs are soaring, and two-thirds will need some long-term care. At the same time, the retirement system is contracting. Our National Retirement Risk Index shows that 53 percent of households are at risk of not being able to maintain their pre-retirement living standards once they stop working. Given this outlook, while any package will involve some compromise, we should be careful about large cuts in benefits.

Solving Social Security’s financing challenge requires some combination of increased revenues and slowing of benefit growth. On the revenue side, some attractive proposals include increasing the contribution and benefit base gradually to a level covering 90 percent of total national earnings (about $180,000 at current income levels) and gradually eliminating the tax exclusion for group health insurance so that both employee and employer premiums are covered by the payroll (and income) tax. No one wants benefit cuts, but two possible options include increasing the Full Retirement Age (after it reaches 67) to keep pace with improvements in longevity and adopting a “chain-weighted” consumer price index for Social Security’s cost-of-living adjustment (COLA). Adverse effects of the COLA adjustment on the low-income or the very old could be offset by increasing the minimum benefit or making a 5-percent adjustment at, say, age 85.

In short, everyone who cares about retirement security should welcome the restoration of the payroll tax. This change brings the deficit back into manageable territory. Let’s take advantage of this opportunity to eliminate the shortfall and really take Social Security out of fiscal policy debates.