Dueling Social Security Estimates Are Confusing

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

CBO helpful for budget debates, but not for Social Security projections.

I seem to be spending a lot of time on Social Security lately, as a barrage of articles, op-eds, and blogs contend that the program is dramatically more generous than we thought and in much worse shape. The most recent missile is Andrew Biggs’ Wall Street Journal op-ed, “Liberals for Social Security Insolvency.” Biggs notes that 75-year Social Security deficit projections by the Congressional Budget Office (CB0) have nearly quadrupled between 2008 and 2014. He uses the CBO projections to argue that it is foolish to put forth proposals to expand the program.

The angle that I find the most disturbing is the suggestion that Social Security costs bounce around, that we don’t really know what’s going on, and that six years from now they could quadruple once again. Nothing could be further from the truth. The elements involved in these projections are changing at a glacial speed.

On the benefit side, beneficiaries for the next 75 years are already born, and benefits relative to earnings are clearly defined. The only question is how long people will live. On the revenue side, the bulk of the money comes from the payroll tax on earnings, with a fraction from the taxation of Social Security benefits. To project revenues primarily involves projecting the size of labor force and how much workers will earn. Again, most of the labor force is already born, and fertility rates are fairly stable so new entrants can be projected relatively easily. Labor force participation rates change and some assumptions are required for earnings growth, but nothing here is particularly controversial.

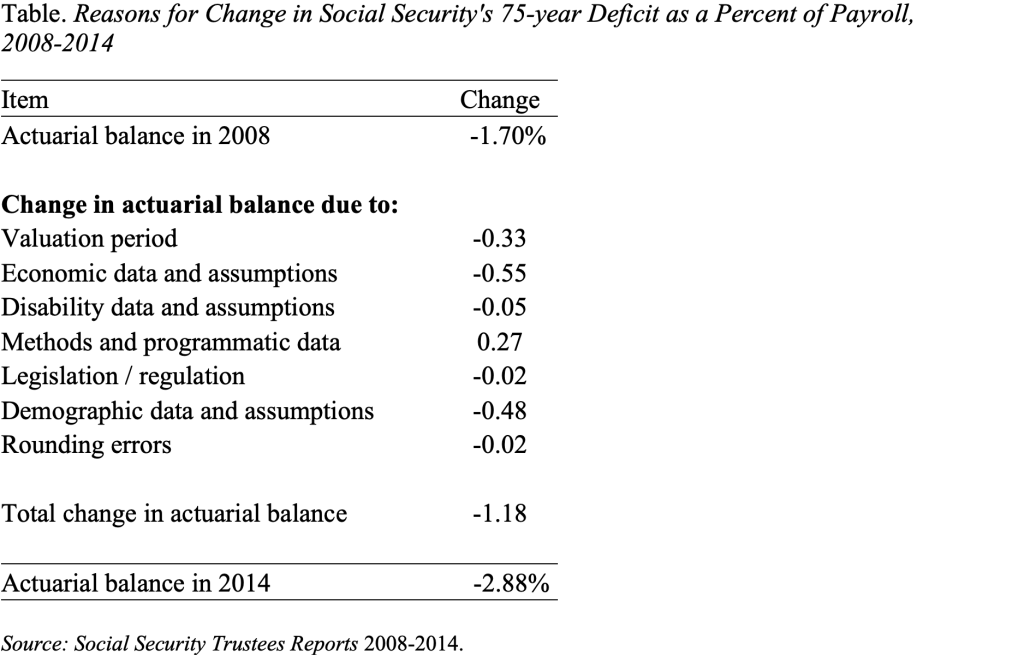

The underlying stability of Social Security finances is evident in the estimates provided by the Social Security actuaries. In 2008, they projected a 75-year actuarial deficit of 1.70 percent of taxable payrolls. (The easiest way to think of the deficit is the required percentage point increase in the payroll tax rate to pay the current package of benefits for everyone who reaches retirement age in the next 75 years.) In 2014, the projected deficit was 2.88 percent. Yes, the deficit increased, but the increase was 70 percent not a quadrupling of 400 percent.

And the actuaries provide an explanation for why the increase occurred – one expected reason, one unexpected reason, and an updating of assumptions. The expected reason is that with the passage of time the 75-year computation adds high-cost years. The unexpected reason is the financial crisis and ensuing prolonged recession, which dramatically reduced employment and tax revenue, and to a much lesser extent caused more people to claim disability benefits and to claim Social Security retirement benefits earlier. In addition, the actuaries updated their assumptions regarding life expectancy, average hours worked, and price inflation (see Table). Absent another financial crisis, all we should expect to see in the future is the steady annual (0.06 percent of payrolls) increase in cost due to extending the projection period, which will continue until the Baby Boom generation is fully retired and then stop.

Such predictability is not true of the CBO numbers. That agency’s deficit for 2008 was way below that of the Social Security actuaries and its 2014 deficit way above. It is bouncing around in inexplicable ways. While the CBO has been a great resource for budget debates, it has not been helpful when it comes to Social Security.